Dancing on the ruins: a festival as a utopian space-time island amid the catastrophes of our time | Letícia Maia (English)

10th October 2025This text by Letícia Maia is her final commission for the Live Art Writers Network x Citemor 2025 project, resulting from a residency involving critical writing and reflection practices in response to live art and performance during the Citemor 2025 festival. You can consult the performance texts generated by Ed Freitas and Letícia Maia, with accompaniment by Diana Damian Martin during Citemor here and find more information about the Live Art Writers Network project here.

Dancing on the ruins: a festival as a utopian space-time island amid the catastrophes of our time. Embodied-symptomatic writing, decolonial thinking, and cuír* temporalities

…

In the streets and buildings of the old village, on the river, in the rehearsal and performance spaces, at the sardine barbecues, at Elsa’s restaurant or at Marinheiro, at Carlota’s house, on the daily rides between Carapinheira, Montemor and Coimbra, in the bars after performances, at Xavier’s family home that welcomed us, in the meetings, rehearsals, lunches, dinners, open processes, endless conversations — time and space seemed to twist together in coexistence and sharing. It was not just about watching shows, but about accompanying gestures in movement, works in search of themselves, living with the community that, in its web of relationships, forms the living network that sustains this festival.

The invitation to accompany Citemor was not just a call to observation, but a call to practise “respons-ability” (HARAWAY, 2019): the ability to respond reciprocally and embodied to the works, the artists and the network of relationships that make the festival happen. But how can we put into words an experience that is inscribed in the body? How can we give shape to a thought that arises from the disorientation of the senses (AHMED, 2019), from the suspension of habits, from the encounter with the otherness of art and the community that makes it possible?

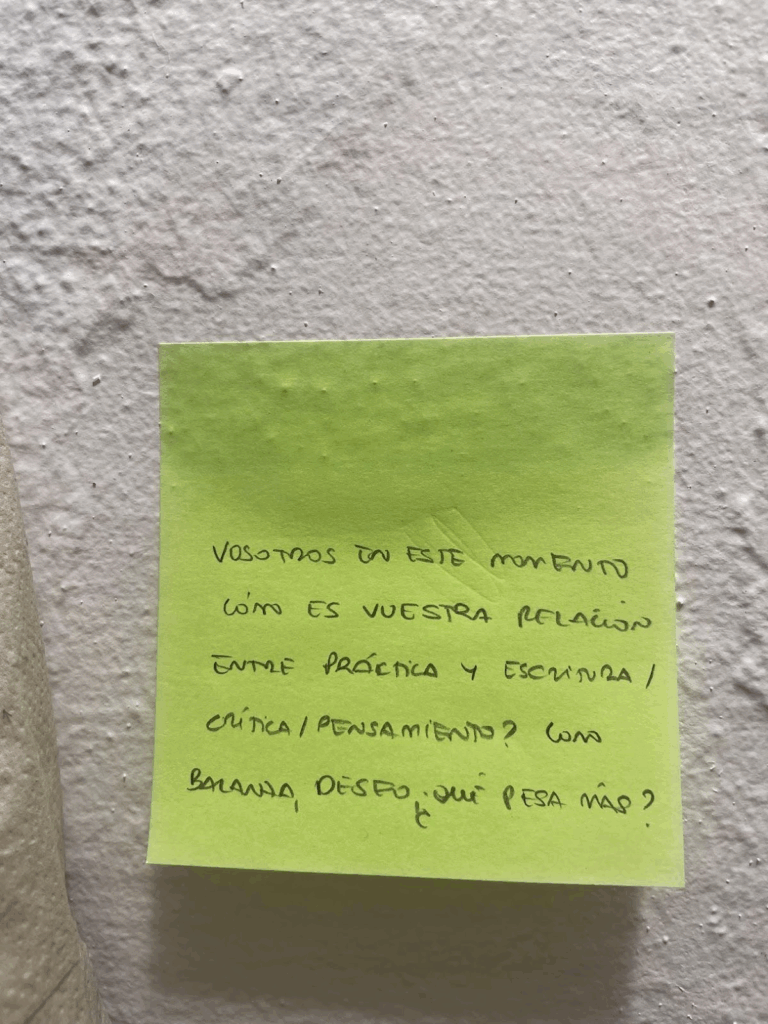

From my position as an artist and researcher, whose main focus is not critical writing, this invitation was a great provocation. It was a move that took me out of my comfort zone and threw me into an immersive situation of reflection and writing at a pace and volume I had never experienced before. Alongside my residency companions Ed and Xavier, and the virtual presences of Anahí and Diana, Ed and I, each in our own way, invented ways to respond to this provocation while the festival was taking place – here are the texts we wrote during the festival. (link).

Accompanying such a diverse and complex set of works and writing simultaneously with the festival meant mapping out what was pulsating most intensely and urgently in the moment, bringing a more immediate, almost instantaneous characteristic to the writing, in response to the unique ways in which each work affected me.

This experience brought to the surface questions that have stayed with me ever since: how can we unlearn familiar formats and make room for a writing practice that is also experimental? How can we write-think with and from the experience, imbued with the performative reverberations of the event, allowing it to contaminate the very act of writing?

This text arises from this area of friction: the body that experiences the event and the urgency of writing that does not seek to capture it. As an artist, whose primary material is embodied experience, writing emerges not as an act of representation or capture, but as a practice of speculative fabulation (HARAWAY, 2019, p. 45), an attempt to weave, with the threads of lived experience, a cat’s cradle (string figures) that, in a gesture of giving and receiving, can be modified and passed on so that affections and thoughts proliferate in other fields (HARAWAY, 2019, p. 45). It is an attempt to articulate, based on a situated experience, a practice of writing that is itself a way of dancing on the ruins, of cultivating a thought that emerges in the encounter with the significant otherness of art and the community that makes it possible.

Writing with and from the performing arts, due to its ephemeral and phenomenological nature, always carries the risk of functioning as a device of capture — of freezing the event, of transforming the experience into a report, into stagnant memory, into a hard archive. In the text “A Certain Impossible Possibility of Saying the Event,” Jacques Derrida (2001) reminds us that the act of “saying the event” is traversed by a fundamental impossibility; it escapes the moment we try to name it. This is because saying, by its very structure, ‘is condemned to a certain generality, a certain iterability, a certain repetitiveness, [and therefore] always lacks the singularity of the event’ (DERRIDA, 2001, p. 236). Language, in attempting to name what is unique and unpredictable, inevitably fails to do it in a generality that always comes after the event.

However, this limitation also opens up another path. If writing fails to live the event, it inevitably ends up doing so in another way. It ‘intervenes and interprets, selects, filters,’ becoming a production in itself. Writing is, then, a symptom, a spectral reappearance of the event that resists total appropriation. To assume this ‘failure’ as a creative gesture means, then, to abandon the pretence of capture and embrace writing as a process of creation, a symptom: a signifying of the event that ‘no one dominates, that no consciousness […] can appropriate’ (DERRIDA, 2001, p. 247). It is not the quest to unravel the secret inherent in every event, but to recognise that ‘the secret belongs to the structure of the event’ (DERRIDA, 2001, p. 247). Writing thus becomes walking blindly in the dark, not as a way to find the exit, but to trace the errant map of one’s own stumbling, operating under the logic of ‘perhaps’ — the only modality, according to Derrida, that can get close to this experience of the impossible.

Writing, especially writing focused on normative art criticism, also carries the spectre of distance and the supposed neutrality of the writer. This is a cursed legacy of the so-called “universal” subject, who claims to be neutral, but who has always been clearly marked – male, white, heterosexual, European, middle class. Donna Haraway refers to this stance as the ‘conquering gaze that comes from nowhere,’ a gaze that represents the unmarked positions of ‘Man and White’ (Haraway, 1995, p. 18). Suely Messeder also denounces the way in which modern capitalist science has forged neutrality in favour of a universal ideal, even though it is aware of the concrete existence of the “white Western epistemic incarnate subject” (Messeder, 2020, p. 48).

Feminist epistemologies have already taught us that there is no universal subject, nor is there any possibility of neutrality and distance. Instead, there are situated bodies, positioned intersectionally by social markers that place them within the tensions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nationality; bodies traversed by wounds and desires. All knowledge is localised; both abstraction and supposed objectivity are ways of establishing and maintaining relations of power-knowledge.

Thus, the relationship with artistic works is always intersubjective; their meanings emerge in a relational and contingent manner, in constant negotiation with contexts, positionalities, affections, and circuits of desire that traverse those who see and write. As a cis, white, bisexual, artist, Brazilian, and immigrant woman, I speak from this situated place. My relationship with works and writing is therefore permeated by this position, which guides my ways of seeing, feeling, thinking, and positioning myself. This is not a biographical detail, but a turning point that informs my listening and my gaze: the experiences I carry – of gender, sexuality, displacement and creation – act as lenses that modulate both the questions I ask and the answers I venture. Thus, writing is never a neutral gesture; it is an embodied act, in which memory, desire, affection, and context intertwine and reverberate in the readings I propose.

It is within this context that Messeder proposes the figure of the “embodied researcher”: one who recognises their biographical trajectory and assumes that all knowledge arises from a “corporeal subjectivity” (MESSEDER, 2020, p. 48). For Messeder, knowledge is not abstraction, but body, memory, and experience; writing is always situated, embodied, and intertwined with the identity and history of the writer. Against the epistemic violence that sustains normative knowledge — excluding voices and forms that do not fit its moulds —, the author defends a “blasphemous, multi-referenced, experimental and decolonial” knowledge (MESSEDER, 2020, p. 439), in which blasphemy functions as a political method to break with the asepsis of pure reason and embrace the contamination of thought by the body, ancestry, and community. This proposal confronts the coloniality of knowledge, which imposes a technical-scientific rationality, supposedly neutral and universal, and silences subalternised knowledge. Incarnate writing — insurgent, critical, and performative — is thus a gesture of resistance to colonial structures of knowledge, as it holds together dimensions that the modern paradigm has separated: body and thought, affection and reason. A blasphemous science, as Messeder calls it, challenges this colonial separation and reclaims ways of thinking in which life and knowledge are not apart.

Inspired by these reflections, I seek here to approach a symptom-embodied writing based on the still pulsating presence of these experiences and this insular territory in my body. Writing with and from artistic works — which are also forms of thought, aesthetic and imaginative elaboration — implies cultivating a practice of attention to the work of others that does not seek to grasp what it ‘means,’ but rather to open oneself up to being affected with one’s whole body. It is, as Eleonora Fabião suggests, a matter of shifting the focus from an ontological problem to a “performative interrogation” (FABIÃO, 2009, p. 245): what does this work do? What can it do? To me, to the other, to the world? This change in perspective is crucial: instead of seeking a hidden truth in artistic work, writing turns to its effects, to the forces it mobilises.

In this twisted space-time of the festival, writing became for me a practice of thinking, an exercise in dialogue with the works and not about or against them, a gesture of resonance and reverberation that escapes the pretension of normative synthesis. My writing here is not intended to be a critical report; it seeks to be closer to a living, corporeal, provisional, precarious archive, in order to give form to the affections that traverse the body. An incarnate-symptom writing that is blasphemous, challenging normative knowledge and opening space for undisciplined ways of thinking. Writing from this point of view is to recognise the risk of capture that all writing carries, which is perhaps why writing needs to twist itself together with time, inhabiting the interval, the deviation, the curve.

This methodological blasphemy is also a cuir gesture: rejecting linearity, moving within other timmings, inhabiting undefinedness. This perspective echoes the disorientation of Sara Ahmed, for whom cuir is a matter of disorientation and reorientation — turning to unexpected sides, rejecting pre-tracable paths (AHMED, 2019). Writing with the body and not against it, like someone who listens to whispers, like someone who allows themselves to be impregnated, like someone who touches and allows themselves to be touched. Writing that is done by doing, performative in its effects, deviations and twists.

…

As I pull at the sensitive thread that inhabits my body after following such distinct processes, rehearsals, and performances, I realise that one question haunted many of the works presented at the festival, perhaps echoing the ‘spirit of our time’ that weighs heavily upon us: how to create amid the collapse — wars, global crises, political and social setbacks, the growth of the far right, fascism, the ongoing ecological catastrophe — that permeates our lives?

It is not difficult to see that the reality we live in is collapsing, the effect of a way of life imposed by power structures that intersect colonialism, racism and patriarchy. To name the complexity of this era, Haraway proposes a series of interconnected terms: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene and Chthulucene (HARAWAY, 2016). Each term illuminates a facet of the crisis. Anthropocene points to the massive geological impact of a part of the human species; Capitalocene specifies that it is not about ‘humans’ in general, but about the logic of infinite capital accumulation; Plantationocene reminds us that the roots of this devastation lie in the monoculture practices of plantations, a model of ecological and social simplification that has become global. Finally, Chthulucene is the name Haraway gives to chthonic forces and powers, to the multispecies webs that persist amid the ruins, inviting us to think and create with other earthly entities, human and non-human.

In dialogue with Haraway, Isabelle Stengers points out that the problem is not the action of ‘humans’ in general, but rather a civilisation that, under capitalist, patriarchal and colonial logic, promotes the ‘intrusion of Gaia’ (STENGERS, 2015, p. 35). In times of catastrophe when, as the author warns, ‘our historical beliefs have put us in limbo’ and the slogans of ‘development’ ring hollow, it is not a question of dreaming of universal solutions, but of learning to ‘resist the approaching barbarism’ by inventing devices that destabilise hegemonic narratives and teach us to pay attention (STENGERS, 2015, p. 15).

In this context, the question thus returns: how can we create in times of catastrophe? How can we produce works that open up like cracks, folds, flashes of worlds to come? I raise this question not to answer it, but to keep it as a problematising guide. In the context in which the festival takes place, in Europe, with works produced by European artists, I realise that this atmosphere I felt is the effect of a malaise produced by a perception that the world governed by colonial logic is in ruins, an effect of its own action. Some works, each in their own way, exposed this unease and proposed encounters within the collapse, movements in the fissures, attention to the fragility and intensity of the present — a present traversed by end-of-the-world rhetoric and by affections that destabilise certainties, calling for listening to futures that are still possible.

Suely Rolnik (2018, p. 17) speaks of a “collective and creative management of malaise” capable of allowing other worlds to germinate. This malaise, she says, is connected to the “colonial-capitalist unconscious” and the urgency of its decolonisation. Social transformation, Rolnik reminds us, is not limited to macro-politics, but is gestated in the ‘modification of the micro-political devices of subjectivity production’ (ROLNIK, 2018, p. 19). The insurrection begins in the body, in the refusal to surrender vital power to the ‘pimping’ of desire for capital.

Davi Kopenawa, in The Falling Sky, reminds us that destruction is not a distant metaphor, but a concrete threat. For his people, collapse is not a novelty, but continuity. The fall of the sky, as he warns, is not a distant myth, but a real danger that will affect us all, white and indigenous, if the shamans can no longer ‘sustain the sky’ (KOPENAWA; ALBERT, 2015, p. 214). His words teach us that the future depends on ancestral memories and the invisible worlds that persist; to listen to him is to recognise that the words of the shamans, engraved in thought and continually renewed, are a living archive that contrasts with the ‘paper skins’ of white people, marked by forgetfulness (KOPENAWA; ALBERT, 2015). This listening is not allegory, but embodied memory and future, a call to shared responsibility and the urgency to rebalance worlds.

The metaphorical image that gives this text its title — ‘dancing on the ruins’ — proposes artistic practice as a form of micro-political resistance in the face of the state of collapse we are experiencing, but the ruin here is not a metaphor for a generic catastrophe, but rather a precise political gesture in the face of a specific scenario. Contemporary landscapes are filled with what Anna Tsing (2019) calls ‘ruins,’ and the ruins we inhabit are the material and subjective legacy of the Colonial Matrix of Power (CMP), the logic that, over the last 500 years, has organised the economy, authority, knowledge and life itself around a racial and patriarchal hierarchy (MIGNOLO, 2017, p. 8; LUGONES, 2008). This is the ‘colonial-capitalist unconscious’ that Rolnik (2018) describes as a regime that “pimps” the vital drive, and it is the destructive logic of the ‘People of Commodities’ that Kopenawa denounces as responsible for the ‘fall of the sky’ (KOPENAWA; ALBERT, 2015). This matrix operates through a ‘Great Division’ that separates Nature from Culture, object from subject, the non-human from the human, establishing ‘two entirely distinct ontological zones’ (LATOUR, 1994, p. 14). Recognising this is the first step towards understanding that the contemporary crisis is not an accident, but a project.

Faced with the urgency imposed by a state of collapse, it is vital to create spaces where we can live together in difference, deal with discomfort, cultivate relationships that are not based on hierarchy and exploitation, but on listening, reciprocity and collective invention. Creating, here, is not just about producing artistic works or objects, but about opening up possible worlds: ways of being together that are capable of undoing the separations instituted by the Colonial Matrix of Power, of creating links between bodies, territories, memories and different temporalities. These gestures, like those I witnessed in many of the festival’s works, do not offer definitive answers, but rather rehearsals that take risks amid the ruins, pointing to practices of creation amid collapse, gaps where political imagination can proliferate.

An example of this is Exercício de Montagem (An Exercise in Staging), by the Portuguese group Teatro de Vestido, directed by Joana Craveiro and presented as a work in progress showing, the result of a creation residency during Citemor. The play emerges from one of the greatest ruins of our time — war, or rather, the genocide perpetrated by Israel against the Palestinian people — and calls on the audience to listen in a way that is at once political, ethical and sensitive. The dramaturgy is not presented as a linear narrative, but as a polyphonic flow in which image, voice, gesture, music and cinema intertwine.

The play is organised into different layers that overlap simultaneously. In the foreground, Joana and Tarab, narrators standing in front of microphones at the front of the stage, recount stories collected from people living in the occupied territory of Palestine in the third person, combining historical data, quotes from poets and personal accounts. Translated into Portuguese, English, and Palestinian Arabic, these voices make audible memories and presences that the West insists on reducing to the condition of ‘less than human.’ The presence of Tarab — a Palestinian artist who lives in the territory occupied by Israel — and the centrality of the use of her mother tongue on stage shift the viewer’s gaze and body: it is an eruption of resistance and resilience that humanises those whom the genocidal Israeli government seeks to erase, producing a state of vertigo in which body and thought are challenged by sensitive listening that demands responsibility.

In the background, other performers manipulate sound, images, land-models, documents and the video itself on editing tables, making the creative process visible. In the foreground, the “film” under construction combines recordings made in Palestine with images produced live on stage: conversations with residents, historical archives, photographs, maps, and cities in ruins recreated in miniature. This aesthetic choice is also a political gesture: it exposes the artifice of editing, revealing the scene, the editing, the music, the cuts, the manipulation. By showing that nothing we see is natural or inevitable, but rather constructed, Exercício de Montagem denounces the colonial and genocidal structures perpetrated by the State of Israel, re-inscribing the silenced voices that speak for themselves in a field of dignity and care — without, however, falling into the error of speaking for them or “giving them a voice.”

In this interplay between planes, the scene becomes a polyphonic territory, where document and movement, vulnerability and resistance, archive and oral storytelling coexist. The play not only reveals the intolerable, but insists that we cannot ‘unsee,’ ‘not know, not want to know.’ The presence of Tarab and their language being at the centre of the stage is a performative act of re-inscription: a refusal of abjection and an affirmation of the life of a people as a force of resistance. In this sense, Exercício de Montagem is less a play ‘about’ Palestine than a practice of dismantling and reinventing the gaze: a sensitive pedagogy that exposes the processes of representation while returning us to reality in its rawness, demanding that we take an ethical stance in the face of the violence perpetrated by Israel and its genocidal government.

The show also stages the forced precariousness of a people — a life made ‘unliveable’ by colonial-capitalist logic — and transforms it into a political gesture. Its strength lies not in offering answers or solutions, but in opening up a space of ethical discomfort, of critical displacement, in which the production becomes a practice of micro-political resistance. Every translation choice, every gesture in front of the microphone, every scene, every visible manipulation of sound and image produces a politics of attention, insisting on inventing possible worlds amid the ruins.

I confess that I left the theatre choked up, with an indigestible weight in my stomach, not knowing exactly how to put into words how the work affected me. Still, given the role entrusted to me at the festival, I felt the need to rehearse these few words, even though I understand that anything we can say in the face of the intolerable always seems insufficient, even outside the temporality of the festival. Watching this process was to realise how the open, collaborative, sensitive and procedural scene — constructed between document and gesture — can operate as a form of resistance in the face of cruelty and violence that seems unspeakable. The use of third-person oral narration, the fragmentation of narratives, and the simultaneity of languages, structure a polyphonic dramaturgy that dismantles colonial narratives and reveals the layers of mediation of the gaze. At the same time, the scene refuses any neutrality in the face of violence: it protests against the silencing of the genocide in Palestine and affirms the ethical responsibility not to remain silent in the face of the intolerable, explicitly naming the State of Israel as the perpetrator responsible for this policy of death.

Thus, Exercício de Montagem not only denounces, but creates. It insists on making the stage a place of care and attention, where the technology of staging — scene, sound, image, editing — ceases to be a mere technical resource and becomes an ethical tool. The show invites the spectator to a call to responsibility, to an exercise in listening and presence. More than just witnessing, it is about learning to inhabit the vulnerability of the other without turning it into a spectacle, but as a sharing of humanity. In this gesture, the scene opens a sensitive fold in the present: a space in which life, placed in a precarious position, resurfaces as a power of resistance and political imagination, confronting genocidal violence.

I understand that artistic practices can operate as folds, gaps, flashes that escape the control of colonial-capitalist logic and, precisely for this reason, function as forms of micro-political resistance. If the contemporary crisis is not an accident but a project, creation emerges as that which insists on sabotaging the script: diverting the course, opening cracks, proliferating different ways of life in the space of the possible, opening gaps where the real can be reimagined. Artistic practice, thus, constitutes a gesture of re-enchantment capable of mobilising subtle forces, countering colonial logics. It is in this horizon that Stengers proposes to reactivate practices marginalised by capitalist modernity — such as magic and witchcraft — as forms of political resistance. Perhaps art is precisely one of these practices of re-enchanting the world, capable of acting as a form of insurgency and invention of new ways of life.

…

Citemor is not a festival like any other. With more than half a century of existence, it insists on not surrendering to the hegemonic logic restricted to premieres and the circulation of finished shows. It is more of a laboratory than a showcase, more of a space for germination than exhibition. In this sense, it offers a micro-political counterproposal: a sensitive relationship that sustains processes and coexistence, organised around procedural affectivity. Its strength lies in its malleability and openness — forms of coexistence and art-making that resist norms and linearity. Relationships of trust, care, support, collaboration, affection, and generosity become methodologies that sustain its practice, cultivating a faith in what is to come, a trust in others and in what they do. Thus, even when resources are scarce, the festival insists on the belief that art can exist through resistance and faith in the impossible.

In my first participation in this event, I was delighted and charmed to see how the festival is strengthened by lasting alliances and collaborations, which are built and fortified over time. This network creates a non-normative familiarity – closer to that which Haraway evokes when she proposes “making kin”, the practice of creating relationships of responsibility beyond blood ties. (HARAWAY, 2016, p. 4). It is weaving “oddkin” with humans and non-humans as a way of “sticking with the problem” on a planet in ruins. Accompanying the people involved in the production of Citemor, under the generous guidance of Vasco Neves and Armando Valente, directors of the festival who share the same ground with everyone who works to make it happen, was to experience this practice in action. Among artists who return regularly for residencies, new project beginnings, work-in-progress sharings and presentations, and those who arrive for the first time, the festival space is opened for difference, for the experimental, for what is affirmed as process.

Some texts written over the last few years clearly illustrate this character of the festival. I recommend reading Pablo Caruana’s text written based on this year’s edition, which echoes his position as a long-time partner of the festival. (link). Like Pablo, Claudia Galhós has long been involved in critical writing from within the festival; some of her texts can be accessed here. (link). I also recommend reading the texts in partnership with performingborders, which has been growing stronger in recent years through the Live Art Writers Network project, including the texts that Dori Nigro and Paulo Pinto wrote based on the 2024 edition (link), and the texts that Xavier de Sousa and Anahí Saravia Herrera wrote based on the 2022 edition (link).

In the end, I realise that Citemor is not just a festival, but a promise: a utopian island that emerges from the ruins of the catastrophes of our time, a space-time fold that twists reality and invites us to collectively imagine other ways of being together, showing that possible worlds can still germinate in the precariousness of our present. It is not about escaping collapse, but learning to create within it. In this sense, Citemor operates as a true laboratory of coexistence, where processes are worth more than products, lasting alliances more than ephemeral circuits, trust and care more than competition. By sustaining this practice, it embodies — albeit provisionally and situationally — the promise of other ways of doing things together.

In this way, the festival acts as fertile ground for exercising our political imagination: an invitation to inhabit the present traversed by the future. Not the future of progressive linearity, but the ‘not yet’ of cuir utopia that José Esteban Muñoz speaks of, a horizon that announces itself as a promise and guides the imagination. In this space for imagining political futures not through a straight line, but through the twists and turns of sensitive collectivity — embracing instability, error, failure, and recognising vulnerability and interdependence not as weakness, but as the very condition of possible political strength.

To accompany Citemor was to experience a temporality, curved, twisted, cuirised, that rejects productivist linearity and embraces error, vulnerability, and deviation as material for creation.

This context echoes the disorientation described by Sara Ahmed, for whom caring is a matter of disorientation and reorientation — turning to unexpected sides, refusing pre-determined paths (AHMED, 2019). It is a refusal to reach a final destination, an insistence, to return to Haraway, on “sticking with the trouble” (HARAWAY, 2019), rather than seeking easy solutions.

The critical thinking and writing that arises from this experience cannot, therefore, be that of evaluation or normative synthesis. It must assume the nature of the festival itself: procedural, undisciplined, multifaceted, made up of stumbles, detours and reorientations. More than talking about the works, writing has become for me an exercise in dialogue with them, a gesture of resonance that recognises the risk of capture that all writing carries, but which insists on twisting itself together with time, inhabiting the interval. In this movement, the practice of writing ceases to be an exercise in ordering meanings and becomes closer to the creation of provisional, mutable, and contextual meanings — aligned with the cuir, undisciplined temporalities that Diana Damian Martin spoke of in our conversations. Temporalities that interpolate present, past and future, that escape both normative linearity and end-of-the-world rhetoric and, precisely for this reason, strengthen our political imagination. A writing that fails to grasp and insists on creating, that refuses to be a record or synthesis and prefers to remain as reverberation: open, ruin and promise at the same time.

May critical-reflective writing then be dance rather than discourse, gesture rather than explanation; may it reject the linearity of normative criticism and surrender to the twists and turns of experience. An embodied-symptomatic, blasphemous, cuír, situated writing that insists on germinating futures in the fissures of the present and recognises, as feminist and decolonial epistemologies remind us, that the first territory to be colonised was the body. Perhaps this is why the insistence embodied experience is, today, a fundamental decolonial gesture: to write from the body is also to resist, to reopen the future and to keep alive the power to imagine other possible worlds.

May we commit ourselves to the task of decolonising thought, writing, artistic practices and also the very modes of circulation of art, such as festivals. May attention to marginalised knowledge teach us to deviate from pre-tracable routes, to operate twists, to open gaps and to reorient our bodies and ideas towards other maps of knowledge and practice, towards relationships and temporalities that refuse to submit to colonial and capitalist logics. May art continue to remind us that inventing possible worlds is not a neutral but situated gesture; may we commit ourselves to policies of care, responsibility and insurgency, learning to create from within collapse and to listen to those who, for centuries, have resisted, survived and imagined other worlds.

Letícia Maia, 24 September 2025, Porto, Portugal.

*I adopt the spelling ‘cuír’ instead of ‘queer’ as a political and epistemological gesture of shifting the term from its hegemonic Anglophone and academic origins, situating it within the tensions, affections, and dissident practices of the Latin American context. ‘Cuír’ operates as an inventive and disobedient translation, emphasising the sonority of Ibero-American languages and rejecting the normativities that ‘queer’ has acquired in certain institutionalised circles of the Global North.

References:

AHMED, Sara. Fenomenología Queer: orientaciones, objetos, otros. Barcelona: Bellaterra, 2019.

ANZALDÚA, Gloria. La conciencia de la mestiza / Rumo a uma nova consciência. In: HOLLANDA, Heloisa Buarque de (org.). Pensamento feminista: conceitos fundamentais. Rio de Janeiro: Bazar do Tempo, 2019. p. 161-177.

BUTLER, Judith. Atos performáticos e a formação dos gêneros: um ensaio sobre fenomenologia e teoria feminista. In: HOLLANDA, Heloisa Buarque de (org.). Pensamento feminista: conceitos fundamentais. Rio de Janeiro: Bazar do Tempo, 2019. p. 195-214.

CURIEL, Ochy. Construindo metodologias feministas desde o feminismo decolonial. In: MELO, Paula Balduino et al. (org.). Descolonizar o feminismo: VII Sernegra. Brasília: Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de Brasília, 2019. p. 33-51.

DERRIDA, Jacques. Uma certa possibilidade impossível de dizer o acontecimento. Revista do Departamento de Psicologia da UFF, v. 13, n. 2, p. 231-252, jul./dez. 2001.

FABIÃO, Eleonora. Performance e teatro: poéticas e políticas da cena contemporânea. Sala Preta, v. 8, n. 1, p. 235-246, 2009.

FABIÃO, Eleonora. O que é um corpo em experiência? ou sobre performance, programa e Cia. In: Catálogo da 17ª edição do Festival Panorama, Rio de Janeiro, 2009, p. 18-19.

HARAWAY, Donna. Saberes localizados: a questão da ciência para o feminismo e o privilégio da perspectiva parcial. Cadernos Pagu, n. 5, p. 07-41, 1995.

HARAWAY, Donna. Antropoceno, Capitaloceno, Plantationoceno, Chthuluceno: fazendo parentes. ClimaCom Cultura Científica, Campinas, ano 3, n. 5, abr. 2016.

HARAWAY, Donna. Ficar com o problema: fazer parentes no Chthuluceno. São Paulo: n-1 Edições, 2023.

KOPENAWA, Davi; ALBERT, Bruce. A queda do céu: palavras de um xamã yanomami. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015.

MESSEDER, Suely Aldir. A pesquisadora encarnada: uma trajetória decolonial na construção do saber científico blasfêmico. In: HOLLANDA, Heloisa Buarque de (org.). Pensamento feminista hoje: perspectivas decoloniais. Rio de Janeiro: Bazar do Tempo, 2020. p. 155-171.

ROLNIK, Suely. Esferas da insurreição: notas para uma vida não cafetinada. São Paulo: n-1 edições, 2018.

STENGERS, Isabelle. No tempo das catástrofes: resistir à barbárie que se aproxima. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2015.TSING, Anna Lowenhaupt. Viver nas ruínas: paisagens multiespécies no antropoceno. Brasília: IEB Mil Folhas, 2019.

Letícia Maia (1988, Mairiporã – SP, Brazil) is an artist who lives and works in Portugal. She holds a Master’s degree in Fine Arts from the Faculdade de Belas Artes do Porto – FBAUP (2023, Portugal) and a Bachelor’s degree in Communication of the Body Arts from the Pontificia Universidade Católica de São Paulo – PUC-SP (2014, Brazil). Her artistic practice unfolds in a transdisciplinary field between performance, drawing and sculpture, with a strong interest in exploring the political dimension of the body — particularly issues related to gender, identity, sexuality, and normativity — challenging the ways the body has been represented throughout art history. In recent years, she has presented her work in a variety of contexts, participating in festivals, exhibitions, showcases and artist residencies in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Austria and Portugal. She is currently developing the project “montar corpo”, supported by a creation grant from the Artistas Douro / Porto City Council program, in residence at Mala Voadora (Porto, Portugal). Her recent solo exhibitions include: “Decomposição Tropical” (Júlio Resende Foundation, Gondomar, Portugal, 2025); “MAKE FEMININE” (a project supported by a DGArtes 2023 artistic creation grant, presented at Maus Hábitos – Cultural Intervention Space, Porto, Portugal, 2024); and “D Ó C I L_corpo, genero, poder, e performance” (AL859 Space, Porto, Portugal, 2023). She is also active in the organization and curatorship of performance art events, like Performance Art Shows Movediça_ Mostra de Performance Arte, since 2017 in São Paulo, and trëma(¨), which premiered in 2023 in the city of Porto.

—

The Live Art Writers Network x Citemor 2025 project was conceived and curated by performingborders, Diana Damian Martin and Citemor Festival, with support from Dori Nigro e Paulo Pinto. Funded by Royal Central School of Speech & Drama – University of London, through UKRI Impact Accelerator funding.