- Introduction

- Three listening rituals in Sonic Migrations

- Sitting in the garden, watching the birds with mum…

- Performing Resistance, Care and Labour: Feminist Art and Activism in an Irish Context

- The Anchor, The Drum, The Ship

- Hevaltî – Revolutionary friendship as radical care

- Dayra and Communal Debt

- Budget Commission

- CONTRIBUTORS & CREDITS

- Download PDF

HOW RAISED FLOWERBEDS RAISE QUESTIONS:

NOTES ON THE ANCHOR, THE DRUM, THE SHIP

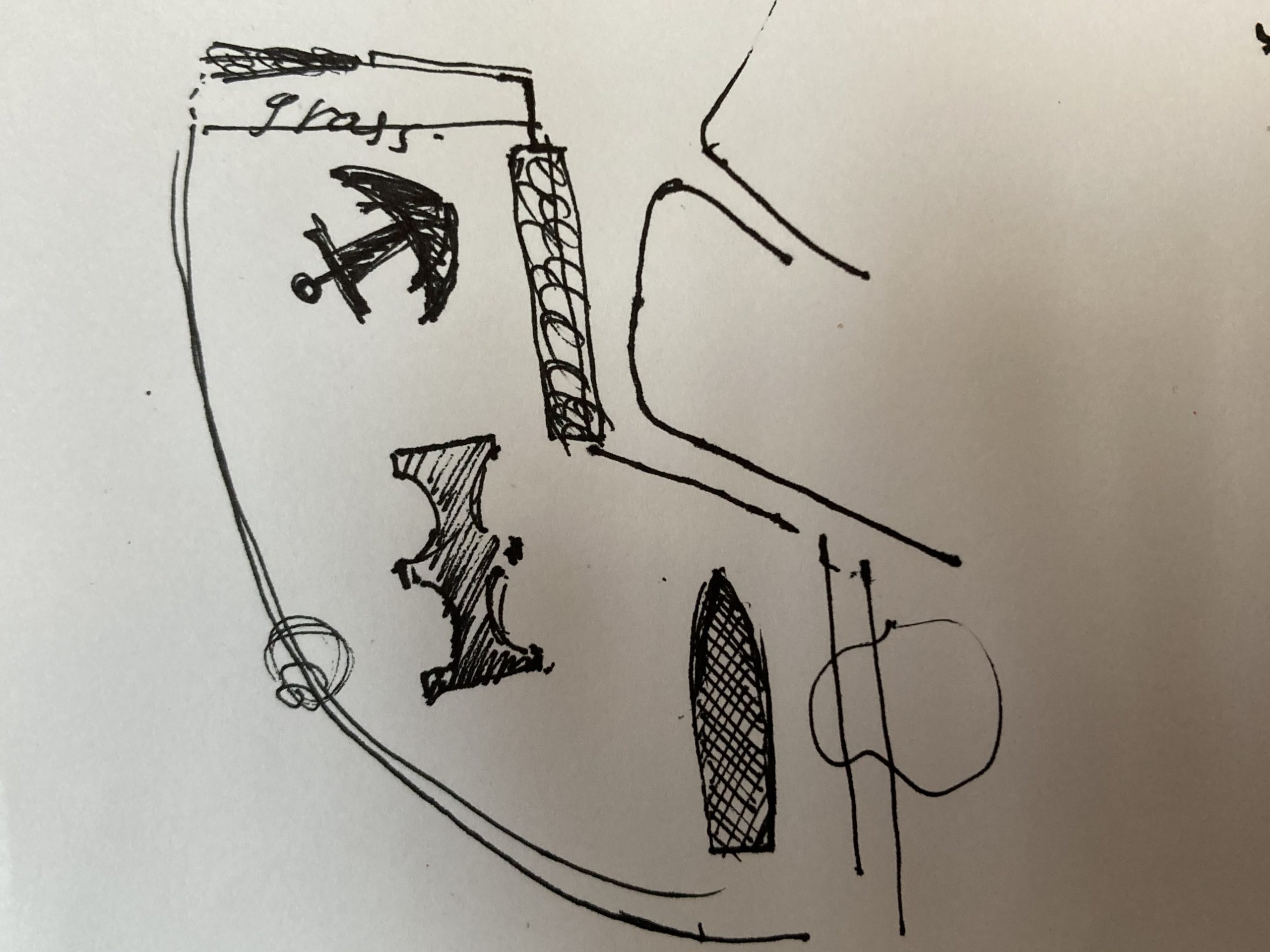

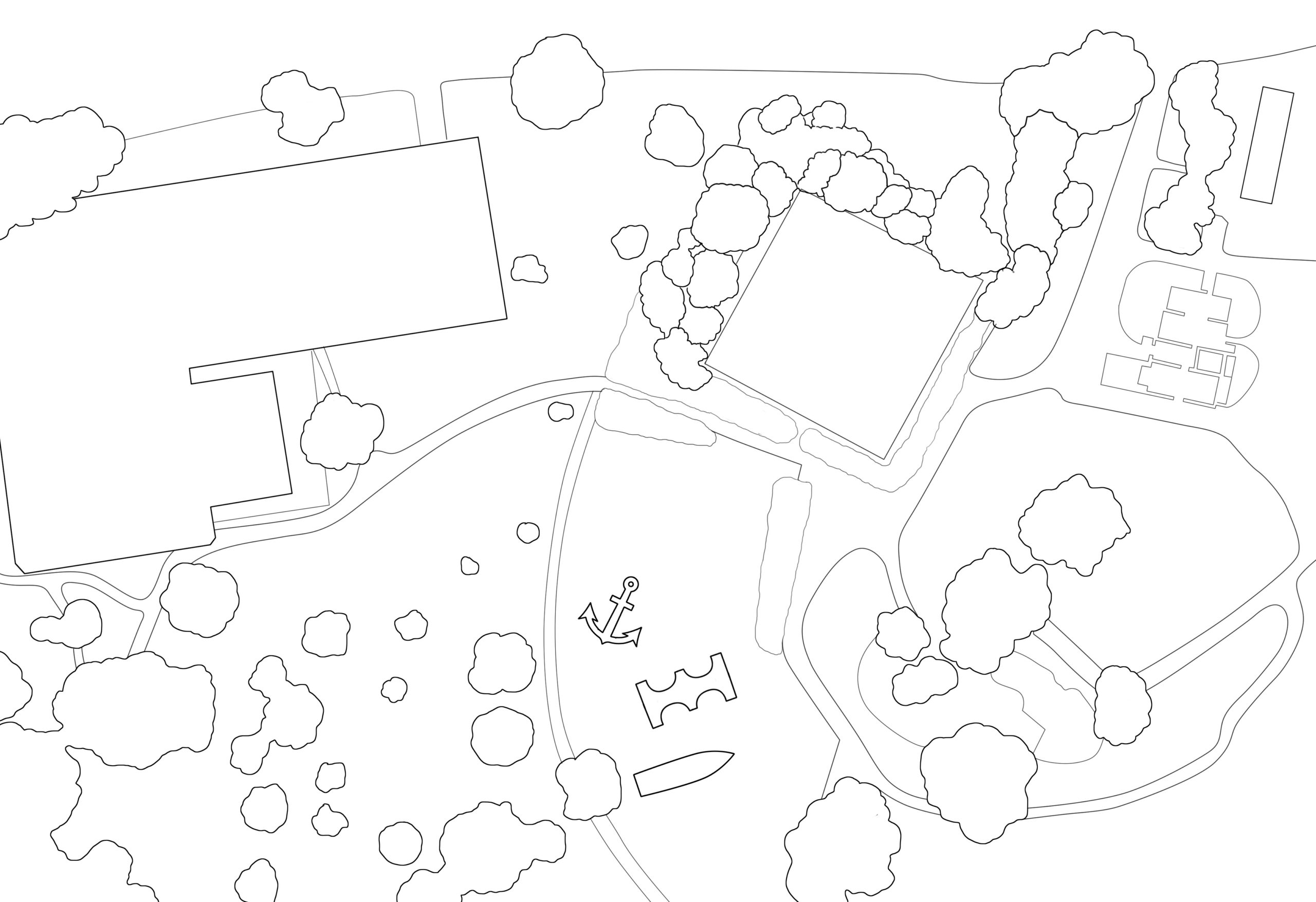

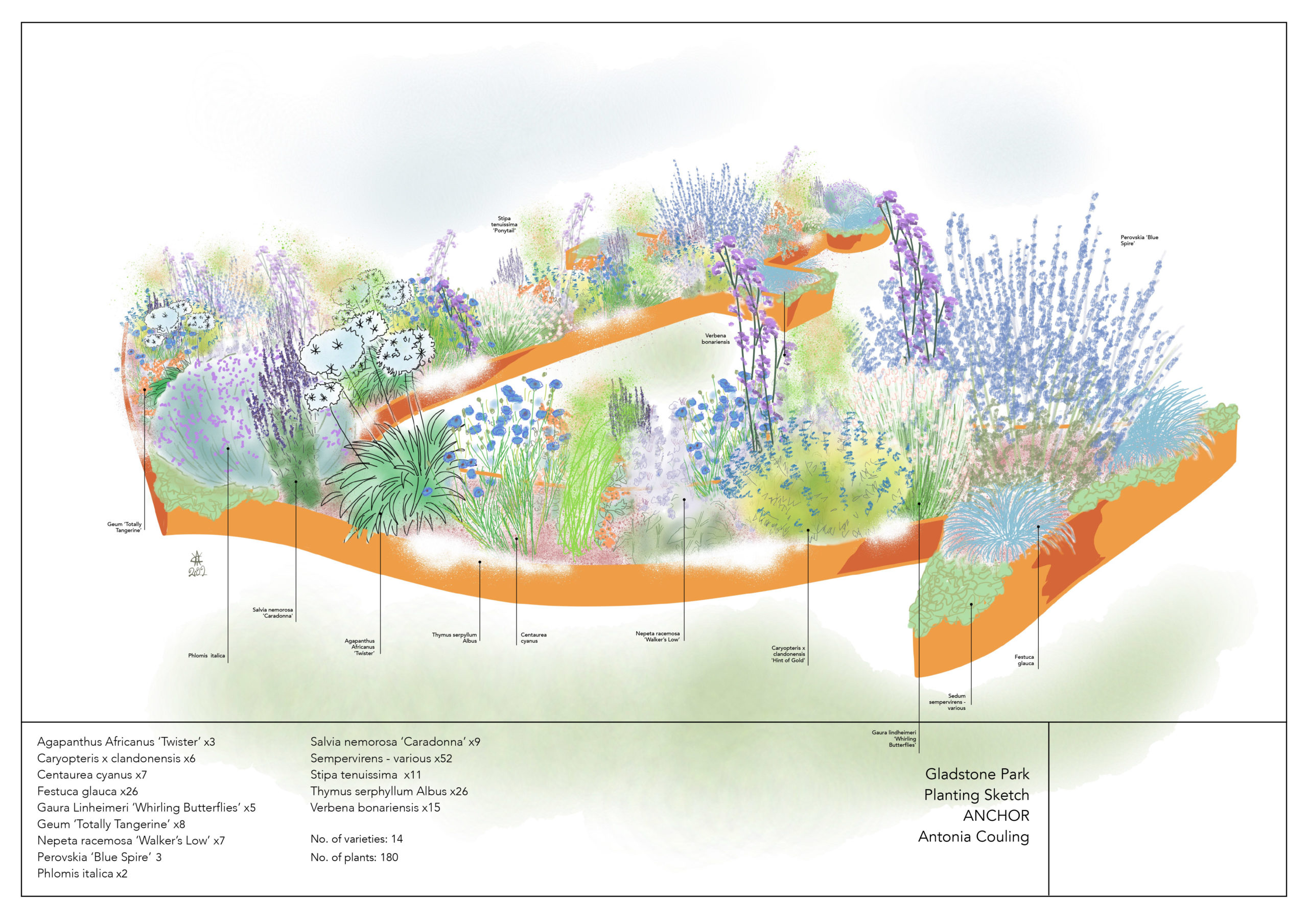

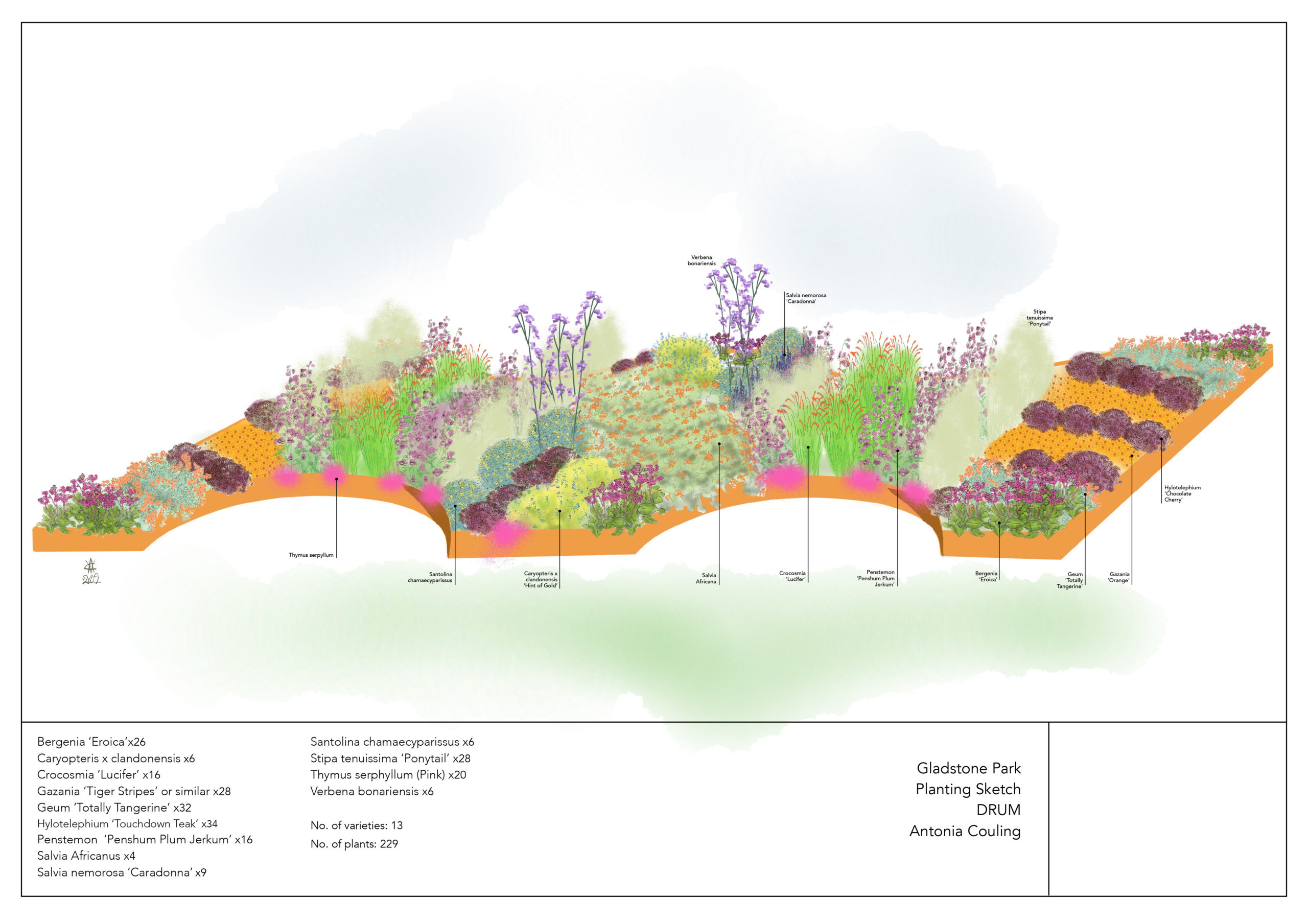

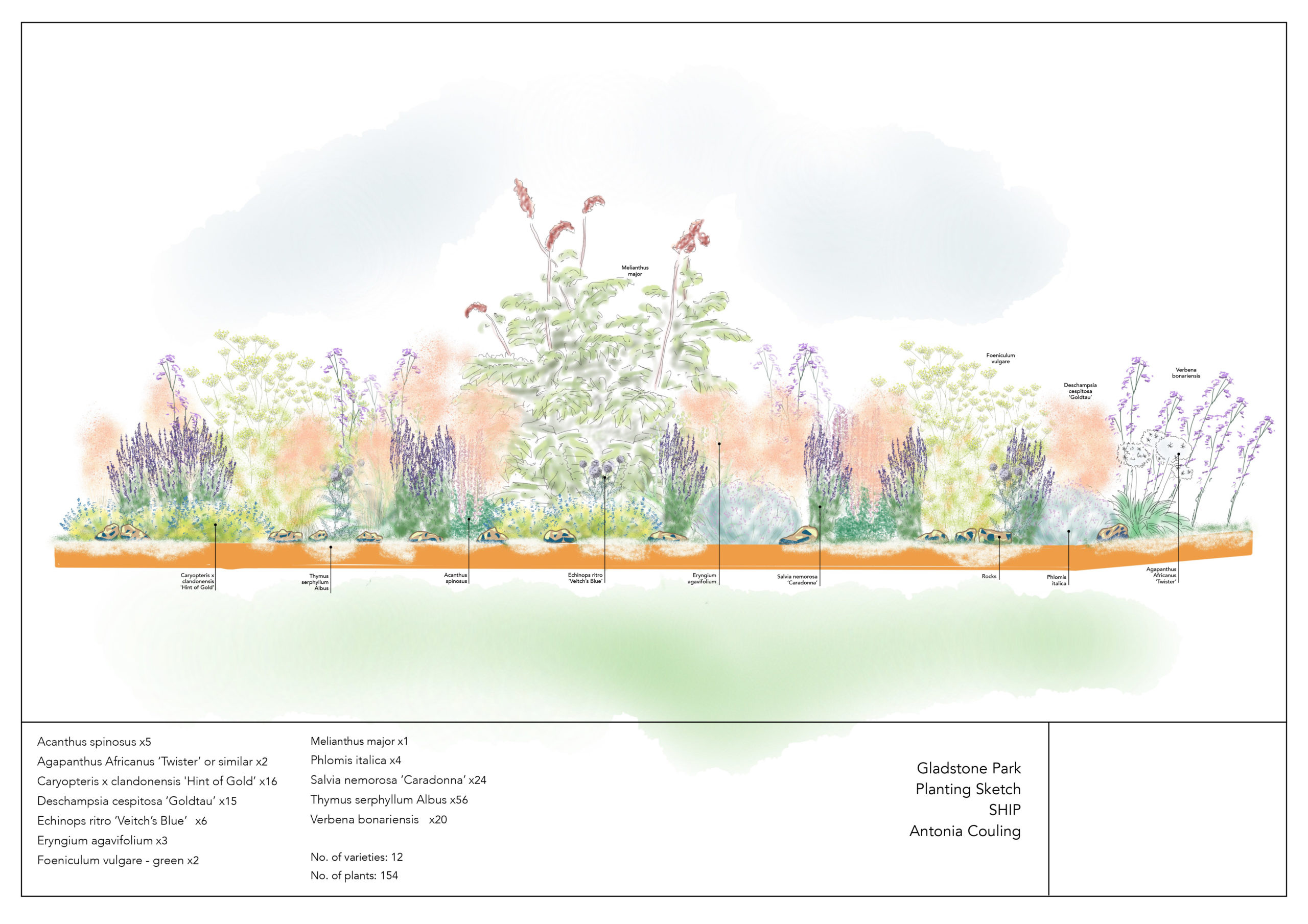

The Anchor, The Drum, The Ship (2022 – ) is an artwork sited in Gladstone Park in North-West London. The installation is a collaboration between myself and garden designer Antonia Couling. The work comprises three flowerbeds, each 10 metres in length, in the aforementioned shapes of the objects in the title. The final planting and bordering of the work took place between the 10 – 14th October 2022 installed by Antonia Couling, a team of professional gardeners doing the planting, myself and a team of heavy-lifters doing the digging and placing the rocks . The work was commissioned by Brent Council and Lin Kam Art.

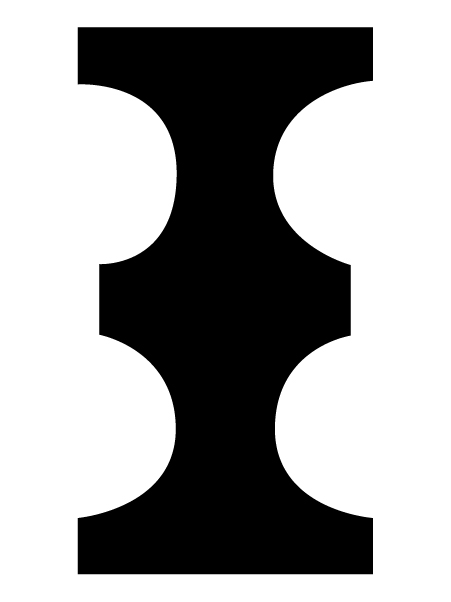

The constellation of symbols (anchor, drum and ship) offer a set of triangulation points to raise discussion around Victorian garden aesthetics, horticulture, plantations, migration and communication. The double-drum (Dono Ntoaso) is drawn from the Adinkra lexicon, a set of Akan symbols used by the Gyaman (also known as Ashanti) people of Ghana and the Ivory Coast. The symbols’ meanings are linked to fables and used to convey wisdom and knowledge. The Dono Ntoaso symbolises united action, alertness, goodwill, praise and rejoicing.

A visual symbol of a thing in the material world, is often a codified simplification of a recognisable shape. In this sense the anchor and ship shapes are very legible to the Western eye. Whereas the Dono Ntoaso symbol is unlikely to be recognised by those who lack familiarity with the Adinkra shapes, perhaps the Sankofa Bird is among the most well known of the symbols through its use in various Black organisation logos, fabrics, jewellery etc. The word Sankofa, can be translated to mean, ‘go back to the past and bring forward that which is useful’.

The anchor symbol evokes maritime histories but could also point to notions of groundedness, or the sunken. As someone who lives on a boat, the ship symbol can also have domestic connotations, and not solely make reference to the slave ship or Empire Windrush. The oldest boat discovered in Africa is the ‘Dufuna Canoe’ and dates to 6500 BC. I mention this to emphasise a longstanding African maritime history that pre-dates the Transatlantic Slave-Trade.

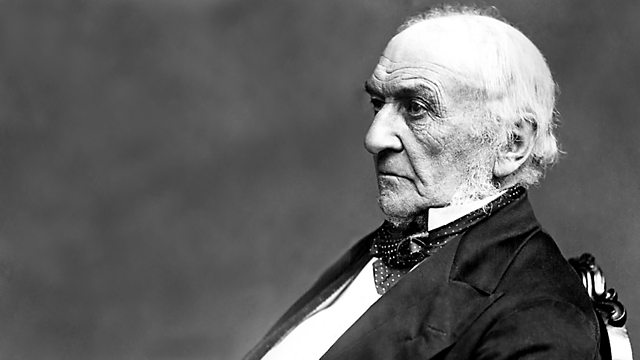

The then existing municipal borough at the time, Willesden (1874 – 1965) purchased the site that was to become Gladstone Park in 1900. The park takes its name after William Gladstone (1809 – 1898) a British statesman and politician, who had recently died. He served for twelve years as the UK’s Prime Minister over four non-consecutive terms between 1868 and 1894. He also served as Chancellor of the Exchequer over a twelve year window. The William Gladstone association lay in the time he spent on one of the properties on the estate, Dollis Hill House.

Dollis Hill House was built in 1825 by the Finch family, it was later occupied by Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks, 1st Baron Tweedmouth (a son of Edward Marjoribanks, a partner of Coutts Bank). After severe fire damage in the 1990s; the Grade II building was demolished in 2012. Today, a purposely incomplete brick structure outlines the ground floor spaces of the house.

William Gladstone’s father, Sir John Gladstone (1764 – 1851) was a merchant and slave owner. After the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, under the Primeminstership of Charles Grey, John Gladstone received more than £90,000, about £9.5m in today’s terms, as compensation for the slaves they were forced to free. He received the largest of all compensation payments made by the Slave Compensation Commission. Gladstone and Slavery (2009) by Roland Quinault is insightful on William Gladstone’s views in this context: “His stance on slavery echoed that of his father, who was one of the largest slave owners in the British West Indies, and on whom he was dependent for financial support. Gladstone opposed the slave trade but he wanted to improve the condition of the slaves before they were liberated.”

Following the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 and the larger wave of anti-racist protests that toppled statues celebrating colonial figures, (notably in the UK, the bronze of Edward Colston in Bristol), there have been amplified calls from community groups in Brent to change the name of the park. There have also been counter petitions to maintain the name.

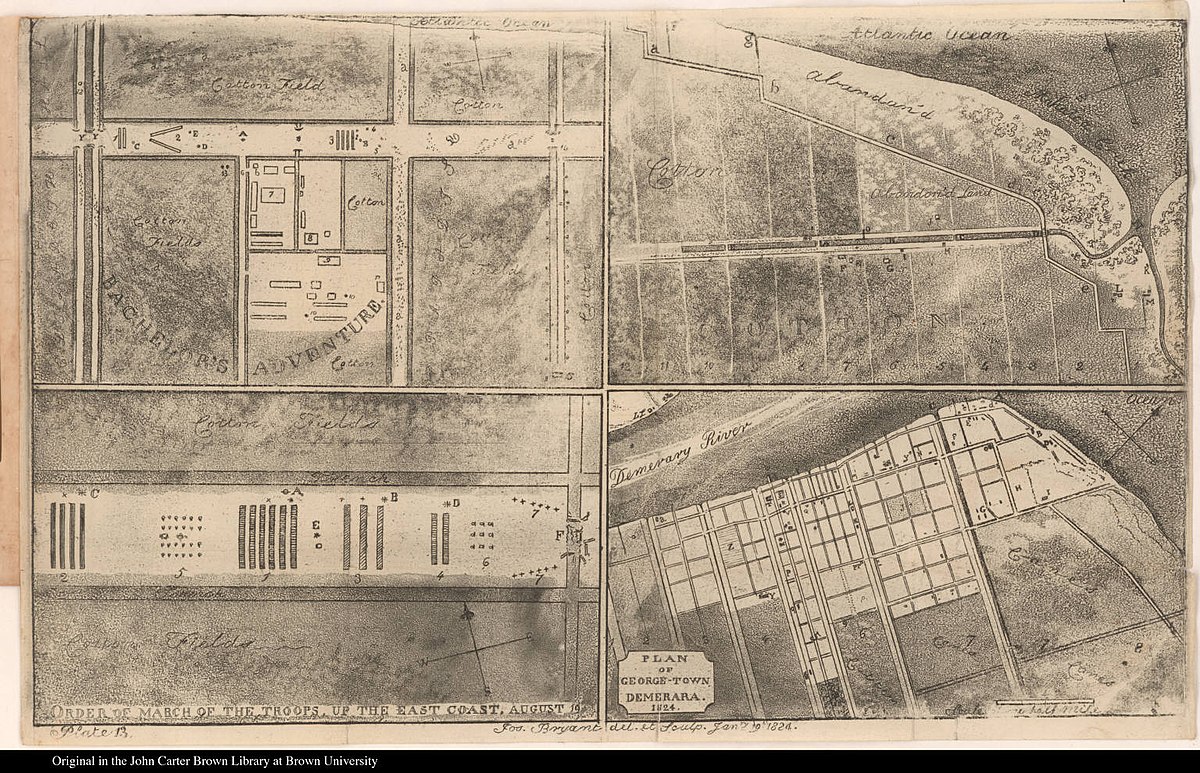

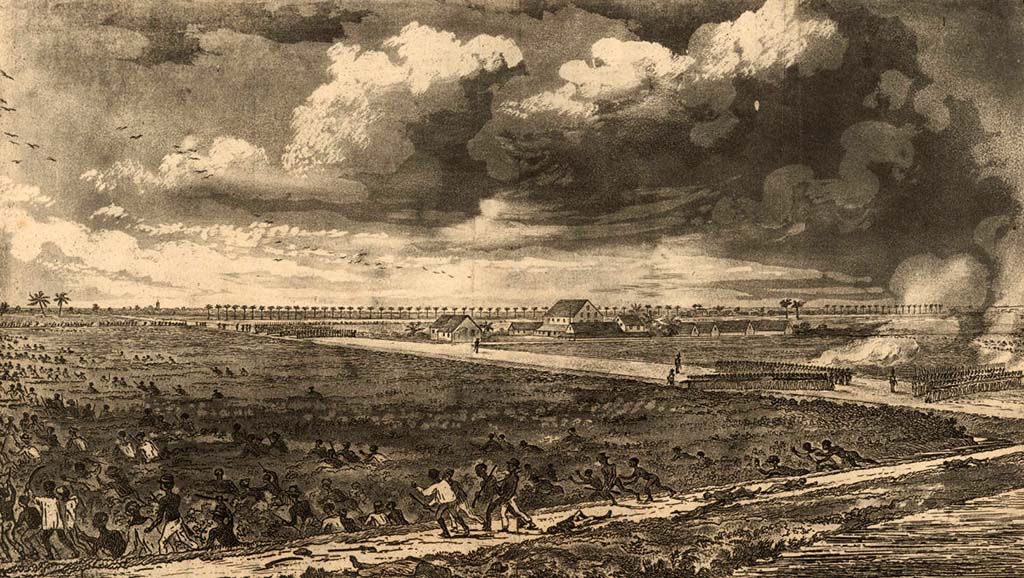

The Demerara Rebellion of 1823 was an uprising on a plantation owned by John Gladstone. The rebellion was believed to be instigated by slaves Jack Gladstone & his father Quamina. Involving more than ten thousand enslaved people and lasting two days the rebellion resonated across the world and was a spur to the anti-abolition movement.

The name of one of John Gladstone’s plantations in Guyana was “Success”. I used this as the basis for an unrealised ground-mural proposal for the park, which has since taken other graphic forms.

In 2021, the then Conservative Government issued new legal protection for what the government’s press release described as “England’s cultural and historic heritage”. Clearly reacting against the call for the removal of particular statues and alterations of names of squares, parks, rooms, streets and so on, led to the brandishing of the suspiciously pithy phrase ‘retain and explain’. One can see the attraction to certain institutions, at one level it’s the closest to doing nothing (depending on the labour invested in the ‘explaining’). There is also a financial cost for councils to the changing of names, removal of signage, changing of letterheads, administrative costs of updating the system – which is another factor behind the reluctance. The cost of an affective pain is pitted against an economic one.

Should the names of all public spaces that take their names after individuals be reviewed every 10 years? I was curious about the consequences of proposing an alternative logic; rather than an alternative name, what if the council declared the park was named after Jack Gladstone rather than William Gladstone? At one level a sleight of hand, but if this pronouncement is accompanied by a committed effort to educate and raise the profile of Jack Gladstone and the Demerara Rebellion, then maybe it functions as a transitional solution.

At the very least the William / John Gladstone name is complicated by being put in association with Jack Gladstone. This unsettles the question of who is assigned the label of hero and whose names are to be enshrined in the social imaginary.

Brent Council currently contracts Veolia (a French transnational company active in water, waste and energy services) to do their park maintenance. As a private contractor – they have a different relationship to the site than gardeners employed by the council directly to care for the land. Veolia calculated their prospective maintenance of the artwork at a much higher rate than a local, independent outfit.

The question as to who and how – the artwork will be maintained after its installation – was a major consideration. Budget for three years of maintenance has been secured by Brent council. This work will be undertaken by Antonia’s company Felicity Garden Design, and a group of people interested in horticulture who will develop to become a parallel group to Friends of Gladstone Park. In this sense, a micro-community is being created to grow around the work itself.

This financial impact could have affected the realization of the work. The park is also reliant on the voluntary labour of the Friends of Gladstone Park who look after certain areas of the park; the areas that they committedly maintain would otherwise be another cost invoiced by Veolia – or done by employees of the council. This also indirectly gives the Friends of Gladstone Park a significant agency in the decision making of what happens in the park.

…

The Anchor, The Drum, The Ship was developed in dialogue with and quotes from other pre-existing aesthetics in Gladstone Park. Notably the walled Victorian era-gardens, which feature a series of intricate perennial beds adjacent to the former stables, now Stables Cafe. Art in public space calls for a set of decisions as to how visually and conceptually disruptive the work intends to be (not that a public reaction can be predetermined). This can be at the level of colour and material – when and why to ‘stand-out’? But also the form itself in relation to the immediate environment. In this case the park is dominated by an Edwardian-gardening aesthetic that has had other more contemporary elements integrated over time.

When is an artwork too polite? ‘English politeness’ is often identified as a mask for passive-aggressive behaviour, can it also be mobilised to smuggle other ideas into circulation?

In the Victorian and Edwardian garden control of the land is performed through the regulation of the planting border. The neater the border the more it signified one had the financial and human resources to maintain the border.

Following discussion with Antonia Couling about the multiple readings one could take from the shapes, she devised a planting plan specific to each of the symbols, which she outlines here:

“The Anchor represents not only associations of all kinds with the sea and what is carried on it, but also the shores of Britain. Sedums and blue grass are planted at the extremities of the anchor on the ‘shoreline’. Running through the central column and branches, however, is a palette of mainly blues and pinks, hinting at an English meadow with its loose grasses and hovering blooms (such as the Gaura and the Centaurea or cornflower), but interspersed are injections of vibrant colour, some shared with the African Adrinka, such as the Geum ‘Totally Tangerine’, and some shared with the Ship, such as the Salvia nemorosa ‘Caradonna’, celebrating the rich cultural mix within those shores. …”

“… The Adinkra drum planting is inspired by Adinkra designs, replicating their bold stripes and sweeps of intense colour. The link between this planting and the Ship’s planting is most evident in the handful of Verbena in the center which will wave tall over the strong identity of the African patterns. African plant species such as the Salvia Africana in the center, Crocosmia and Gazania (or African Daisy) are included. The ship has a taller spine running along its center to suggest rigging (Foeniculum, Melianthus and Verbena). Grasses are interspersed with deep purple Salvias, which will waft to give the suggestion of movement. …”

“… Many of the surrounding plants are also prickly, mirroring the emotions contested history can elicit – that something may seem pleasant enough from a distance, but uncomfortable when seen up close. The low, white Thyme around the edges also hints at sea foam, which is magnified at the front by two Agapanthus.”

Writing about a work that contains live and growing elements, brings a vital element of inconstancy to the system. This is particularly apt when considering a work that might be incorporating historical legacies as a subject. In this sense, although the work is perennial, different elements will flower in different seasons. These flowerings over time can also be read as metaphorical for the different readings embedded in the work – and recognise their own temporality.

On the day the work was formally launched, 14 October 2022, a local drumming group performed by the Dono Ntoaso flowerbed. There was also a poetry reading from Brent-based poet Yasmin Nicholas. Antonia and I gave a tour of the flower beds for local invited residents explaining some of our ideas and the decision-making process.

I am interested in a work that can memorialise without being a memorial, that can generate a relationship with history without being static itself. Among the visible aspects of this work is the hundreds of plants themselves. They will grow and flower and die, embedding these cycles into the installation emphasises the dynamism of what we think is past. The memorial in a traditional sense is built to commemorate a person or event, whereas an artwork can contain this function among others, without this being its primary intent.

⚘ Photography by James Allan

☈ Photography by Caleb Morrison

☙ Photography by Briony Campbell

Images audio-description by Michael Skellern

Harun Morrison is an artist and writer based on the inland waterways. He is currently Designer and Researcher in Residence at V&A Dundee and an associate artist with Greenpeace UK.

Antonia Couling is a West London based horticulturalist and garden designer.