Bodies on the line: Creativity as a tool for struggle | Interview with Danitza Luna from Mujeres Creando (English)

14th August 2023This text is part of Anahí Saravia Herrera’s commission Embodying Resistance/Encuerpando Resistencia: unfinished reflections from the Bolivian territory – see the full commission with further interviews and texts here.

Mujeres Creando is an anarcho-feminist movement based in Bolivia (across many different cities, but with the strongest roots in La Paz). It is a group completely independent of the state, the church, and the NGO industrial complex and has been running for more than 30 years. It takes feminism as a tool for societal transformation, and rejects the liberalization of the feminist struggle for the fight of “women’s rights”, instead taking more radical aims to completely topple patriarchal, capitalist and colonial structures of power. The collective is known for creative actions that take place across the city, as well as for providing legal services for women through Mujeres en Busca de Justicia (Women in Search of Justice), running Bolivia’s only feminist radio Radio Deseo, taking care of a cooperative space Virgen de los Deseos where they host a cafeteria, library and cultural programme, and supporting all kinds of independent self organzing by women fighting for justice. They work with those specifically at the sharpest edge of state violence, the ones that suffer the most oppression and get access to the least support: indigenous women, street vendors, sex workers, domestic workers, transwomen, in short “las mujeres mas jodidas” (the women that are most fucked). Whilst the group is known for their creative interventions, they maintain their status as political agitators and organizers first, using creativity as a tool for their struggle. Their actions are some of the most emblematic feminist interventions that have happened in cities around Bolivia – often using their bodies to take back public space. In the words of María Galindo, the founder of Mujeres Creando:

“No somos un grupo ‘artivista’, porque en Mujeres Creando hay una cantidad incontable de ocupaciones ajenas al arte relacionadas con la producción de justicia, con la habilidad de sobrevivencia colectiva y con la construcción de una relación conflictiva de diálogo y provocación con la sociedad a la que pertenecemos.[…] Nos identificamos y reconocemos colectivamente como movimiento anarcofeminista que ha desarrollado una serie incontable de metodologías de trabajo, algunas de las cuales han sido ocasionalmente recuperadas por ‘el mundo del arte’ y han sido reconocidas como artísticas, aunque su matriz ha sido siempre de la política.” Feminismo Bastardo (p.116), María Galindo

“We are not an ‘artivist’ group, because in Mujeres Creando there is a countless number of occupations outside of art, related to the production of justice, to the ability to survive collectively and to the construction of a conflictive relationship of dialogue and provocation with the society to which we belong. […] We identify and recognize ourselves collectively as an anarcho-feminist movement that has developed an uncountable series of working methodologies, some of which have been occasionally recognized by “the art world” and have been recognized as artistic, although their matrix has always been political.”

To talk through their creative political practice, I interviewed Danitza Luna, a core member of Mujeres Creando, who has a background in art and who now impulses their political work with her creative critical perspectives. I met with Danitza in La Paz at Virgen de los Deseos in December 2022.

Note on translation and the final research:

As someone with access to both Spanish and English, this research has happened across both as well as through local dialects. The final works are edited versions of our conversations, which took place in Spanish with interjections in slang, Aimara and Quechua. The original version of this final text is in Spanglish, with my reflections in English. I have also provided a full English translation. The texts in Spanish were edited with the support of Camilla de la Parra, who also consulted on the translation.

See the Spanglish version of the text, with an untranslated conversation, HERE.

Anahí: Can you tell me how you found and got involved with Mujeres Creando?

Danitza: We as Mujeres Creando have existed for thirty years. I’ve been a part of the group for about eleven years. When I was a newcomer the kinds of questions I had were”What should we do? What do I need to learn?”, suddenly I realise that eleven years have passed. A long time.

Many people have passed through Mujeres Creando, we are not a static movement because there are times when comrades have to interrupt for their activities. There are also comrades who leave us, there are comrades who stay. But before there were even fewer of us that were a part of the group. [Julieta Ojeda has been here almost from the beginning, María Galindo founded this, Helen Álvarez is here carrying on a strong fight for the femicide of her daughter, Emiliana Quispe has also been here longer than me, and then there’s a new generation that comes after.

The radio is a bit older than me, it must be around fourteen or fifteen years old. I came to Mujeres Creando through the radio: I listened to Maria’s programme on the radio, I listened to them and said: “Who are these women?

Anahí: And at that time, were you already a feminist, did you already know about politics, or was that your moment of politicisation?

Danitza: No, actually. Not at all. I mean, it was a very intuitive process. Because I didn’t come from any movement. I didn’t even understand the word feminism. The understanding of intuitive feminism1 was definitely there, there are things that a woman in this country (and anywhere else) notices, right? Like something is always different for you. Why do I, being a woman, have to carry this extra work, this extra burden? Or why does the other guy earn more than me? Yes, I had that understanding, but I never understood the word feminism.

When I heard them on the radio, what attracted me to come here was that they were very coherent and they were doing very concrete things. The art also attracted me here because María was already known for having done several very strong actions here in La Paz. I was just starting my university years, I was in a moment of questioning: “Why did I study this? What am I going to do with my life? What now?” So, at that time I was curious to look for many answers and I just ended up here, at first just taking part in small tasks.

Little by little, I became familiar with the theoretical questions of the movement, the movement’s proposals, and began to contrast this with other reflections that I saw around the word “feminism” here. I understand what you must see there in England, in reality, the [feminist movement] brings here a bad imitation of what they do there, making the feminist struggle more of a job, especially within the NGOs. This is something we call gender technocracy, which is a way of categorising and differentiating ourselves from this type of practice, right? Because, unfortunately, there is an unnecessary complication of the terms within feminist theories. There is an exquisiteness around [making feminism] very academic, which is exactly what happens in England, isn’t it? They want only the universities to handle the theory, they want feminist knowledge to be so sophisticated that not many women can have it and that the grassroots women (those of us who don’t have so much access to these spaces) can only say: “Well, I agree because you know more”. That is what we are trying not to be.

That’s why, looking more at the artistic side, I was more interested in this because I came from a career in the arts, didn’t I? I studied fine arts, I finished and I got my degree, which isn’t really of much use to me (she laughs). But well, [I was able to contrast] those visions of art that are so traditional here, it’s basically the imitation of the academy in Europe, and it was a complete disappointment for me. I said: “Ah, to be an artist in this country is to imitate, it’s to repeat, it’s to submit [to power], it’s to be a social climber, it’s pure careerism, pure classism”. And if that’s the case, I don’t want to be an artist. I don’t want to be associated with being an artist because the social identity that has been generated around what that means is not for me. So when I saw that [in Mujeres Creando] they were doing things that were more artistic, more creative, more interesting, with more impact, with more theoretical background and more concept, I said, this is something valuable, here I can really learn a lot. I came to contribute what I knew. And it was very good because this process was already happening, it was already open, especially by María, […] who had opened this path […] because of the brutal [feminist] concepts that she proposes and because she works with these concepts not only on a theoretical level, but also on a creative-artistic level.

Thinking to her first time taking the streets with Mujeres Creando, Danitza told me about an action they put together for Mother’s Day.

Danitza: I remember the first action I did here for Mother’s Day, was one with featuring crucified dolls, talking about the false morals around Mother’s Day. So we went in a kind of procession where the crosses were there, mothers were crucified as dolls. We gave out a hymn for mothers that was totally changed from the official hymn. It was the first time the group had said: “Who is going to participate? Come on!” And with all my fear, I said: “Why don’t you do it? They need girls” It was quite nice because I think they also planned it so that it wouldn’t be too strong and so that the police wouldn’t come and repress us. It was something very gentle.

This was her first time encountering the public in first person – the next part of our conversation makes reference to political interactions on the streets of Bolivia and why this is such a politicized space. This is also a reflection on the current political landscape in which the current government MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo, previously run by Evo Morales) has coopted many collective movements and also disempowered independent civic-led spaces in service of the party’s agenda. This brought up an important point around what it means to take civic space, who we’re entering into dialogue with when we take the streets, and the legacies of political power we’re speaking to when we do this. Particularly, in a western context that often idealizes so-called leftist spaces in the Global South, it feels important to highlight the nuances of working independently within these territories and the struggles that continue to happen under “radical” governments whose priority often seems to perpetuate their power – despite having offices such as the Ministerio de Culturas, Descolonización y Despatriarcalización (Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalization), which in theory sound like something that the movement should be working with. In these contexts, it has been important for social movements to remain critical and independent of these government bodies, generating a more community-led anarchist critique based on their first-hand experiences as marginalised bodies living in these contexts.

Danitza: It is confronting when people look at you and say: “What is that? Why are they saying that?” Here people are very politicised. Even if they’re are not aware of political terminology, people are very aware of the political issues in this country. People organise collectively in Bolivia. There is a collective sense of self-organisation. What the government really wants to do is to rig that, right? Or they want to dominate that. They want to capitalise on that. There are social movements that were very strong at a certain moment, and now are not even a shadow of their former selves. The COB2 , what used to be the Defensoría del Pueblo3, which no longer exists, the CIDOB4 has been broken into a thousand pieces. There is a fucked-up process of co-optation of social movements and a lot of division. The social movements themselves, self-critically, do not know how to tell themselves that they have allowed themselves to be co-opted.

And in that context, we have often discussed that we are basically one of the

few social movements that are left. Sustaining ourselves as independent, sustaining ourselves as anarchists. Without depending on or owing anything to anyone.

Anahí: A very important part of your practice is the creative interventions you do: you have the graffiti, the cumbia songs, and also more performative actions like the ones you just mentioned. I’m very interested in the question of why use art in political spheres, how does art help to support urgent political work, and how did you come to develop this creative practice?

Danitza: Over time I’ve come to realise that art is not an accessory to the struggle, nor is it decorative, or merely aesthetic. It is something that is interwoven with politics. Very intertwined with the questions of hands-on labour as well. In Mujeres Creando if you want to support us and be a part of the movement, and you also want to benefit and learn, you have to do manual work. You don’t have to be afraid to clean, to wash a dish, to help in the kitchen. You can also do intellectual work or creative work, the latter being the work I lean towards the most. I’m not a lawyer, I’m not a social worker, I don’t know anything about the law to be able to help a woman who is in a complicated situation. But I can have an impact on the symbolic universe that oppresses us. There is a very fucked up symbolic worlds that defines women and reaffirms many things that are unjust for us. With these traditional ideas of what it means to be a “woman”, what does it mean to be a “woman” in Bolivia? Why should a chola5 always be seen as a worker, as a martyr, as asexual? What does it mean to be the ugly one, the birlocha6, the spinster? There are many roles here, because it is a universe of symbolism that is always there to discipline all of us, isn’t it? This is a universe in which I can generate a political incidence, from this artistic work that is not simply reduced to the question of art for art’s sake.

Speaking truth to a feeling I have often felt myself after entering the cultural sector, Danitza also spoke to the continual internal battle that plays out whilst doing creative work alongside activism that can feel more urgent. The questions ‘What is the best thing for me to be doing right now? How can I be most useful to the movement, or my community?’ are part of a continual critical dialogue that underpins meaningful work by artists looking to create as a key part of a wider social movement.

Danitza: I sometimes feel a bit guilty because I have dedicated myself to a field of art that has nothing to do with the many urgent issues relevant to women. What do women need? They need justice, family pensions for their wawas7 …. On the other hand, if we were to dedicate ourselves only to resolving the urgent legal question for women, there would not be a theoretical-conceptual proposal in the background, which is also artistic. We would become an operative arm, firemen to save women from emergencies. So, it’s complicated, it’s seeing all the edges of what the struggle is. […]

I have always struggled with the category of artist. I don’t fight it so much anymore, but it was because of that top-down, vertical quality of the title that my hesitation is still very present. I like the word “creator” a lot more, for example. We were in Mujeres Creando, and one of the girls asked: “Why are we ‘Mujeres Creando’? We could be women fighting, women resisting, women enduring…” (we do a lot of that too).

“It’s Mujeres Creando” (translating to Women Creating) said María, “because if you’re here, that’s why you joined, isn’t it?

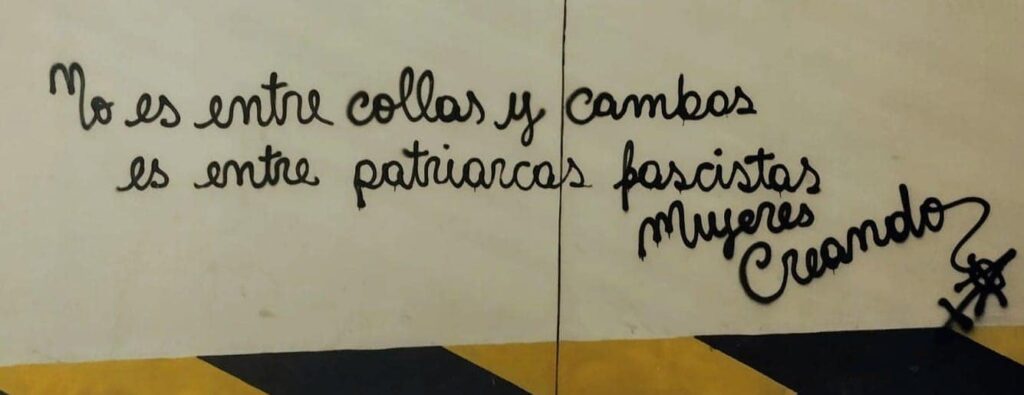

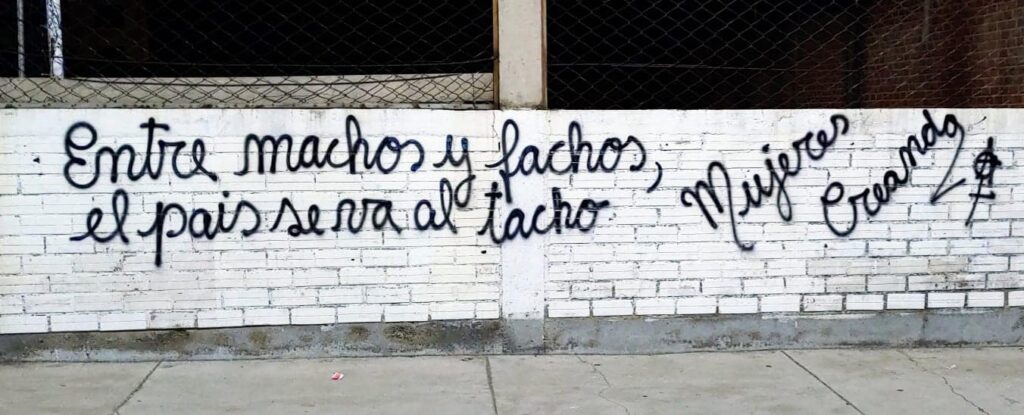

One of our famous graffiti says: La creatividad es nuestra fuerza de lucha (Creativity is the power in our struggle) and it’s true!

Creativity brings satisfaction to what we do, I’m not going to tell you that being here and doing political action is always pleasant, you have to put up with a lot of things. But when you do an action you think a lot about the artistic side, and that allows you [to enjoy it a bit more], it allows you to take space and to rethink what public space is.

The street is always in an internalized struggle of being westernized, to keep itself clean and tidy. The city is always fighting with the women who sell on the street, with the disorder that exists outside. The graffitis are precisely a response to this, because we are not a western society and what we do is intervene in these [westernized] visions, because the discourse of power, the aesthetics of power lie there don’t they? Ordering you, dictating everything to be perfect, all so that you go and produce these paradigms of power in what you do. That’s what I imagine it’s like in England, I don’t know what the urban space is like there.

Anahí: All these tendencies that you describe, you feel them really strongly. At least here in Bolivia, there are still daily interventions by the same women who go out to sell, by people who occupy the streets, nobody does that in England. Besides the fact that it is illegal, people don’t even dare to do it because of heavy state oppression and the fact that ideas of what is right and what makes a “good” city and a good citizen, are deeply internalised by the population. This is also why taking to the streets is difficult (which is a strategy activists also use) and not only because the police repress, but the very imagination of what is possible in public space is quite limited. It always strikes me that there has never really been a revolution in Britain.

Danitza: Here we are fighting so that this badly copied western vision doesn’t take root so easily, right? On the other hand, while there is this western vision, this fucked-up colonialism, there is also the betrayal of the male comrades who are from indigenous movements or alternative spaces, those who are on the left but are willing to negotiate with the bosses, and who don’t even take women into account. It’s like this double oppression, isn’t it? On the one hand, the colonizing patron and on the other hand, your own comrade, who can be as indigenous as you, or your leftist comrade. […] A good way to confront all these discourses at the same time is art and going out into the streets.

Maybe this is something you see as a strategy. You say a “strategy” could be to take to the streets, but here there is no other way. Here, the street is the ultimate stage for social contact and social struggle. Here you can’t comment on a social reality if you don’t do it in the street.

Looking at the street as the ultimate public stage, Danitza also speaks to how the use of the streets in different ways has always been a part of Mujeres Creando’s practice. Beginning with a pamphlet in the 80s titled “Mujer Pública”, they expanded into graffiti, leaving verses and poems on the streets where they could be encountered and re-encountered in a more democratic way, drawing performative meaning from their public context.

Danitza: It’s not a question of pamphleteering, but rather of generating an interruption to a discourse that is omnipresent and tells you to submit to power, to shut up, to not talk, to not answer back, and to not rebel. For example, a graffiti I like says: No hay nada más parecido a un machista de derecha que un machista de izquierdas (There is nothing more similar to a right-wing macho than a left-wing macho) and to leave that phrase, I don’t know, in front of the COB (mining union), everyone’s like Waa! They have to erase it quickly, don’t they?

Anahi: I know you have done a lot of interventions, which ones have had the most impact for you personally, or which ones have had a very strong reception?

Danitza: There is one, when Pope Francis came, we did an action to repudiate his visit. The whole country in unison: […] the media, the government, everyone was happy, right? Everyone with the “Welcome Pope Francis” speech. For us, it was also a whole discussion about whether we should do it or not, because there are sisters here who have been nuns. There are comrades who have at some point been aspiring nuns. So you can imagine the conflict and emotional load for many of them.

For the action, we dressed up as nuns. We had some fucked up signs that talked about paedophilia in the Church, talked about them not paying taxes, that they have a lot of privileges, that they have the most expensive university in the country, that they have houses where they have harbored a lot of denounced European priests, and also about their intrusion in the question of abortion and euthanasia… Here the Church has a lot of power.

That action was one or two days before the Pope arrived and the whole country was putting on it’s make-up for his arrival. As we were so well produced, we first went to the Plaza Murillo because that is the territory to conquer. All the power is there. It’s the logic of the pueblo that in the square is the government, the police, the clergy, all together. The point was just to be there and resist, not shout – nothing, but also obviously [we had to] get the images because [that’s important]. If you’re going to do a whole display in public space with so much risk, you have to get some good images to be a record, not only as a record but also to serve as a symbol and a counter-response to a discourse.

At first they didn’t realise who we were, the police came and said: “Mother, can you leave?” When they realised what we were saying, I think some of the nuns even had a pregnant belly (implying it had been the pries), they also realized that María was there, that we had with us various symbols, there was a host showing a Christ with a cross of penises (this was kind of the origin for our Altar Blasfemo (Blasphemous Altar) that we made with María and Esther Argollo)…. So, they obviously then came to drag us out one by one, and the idea was: if they’re going to remove us, they’re going to have to drag us out, but we’re not going to fight either. […]

Then they grabbed each one of us. We were in a chain, we grabbed each other arm in arm, but you can imagine that for nine or ten women, there were about 50 police, especially women police. The first rows are the women, in the second row, the men come and they kick us from behind, they throw pepper spray from below so that you can’t see them, because the press was already there too. […]

Before I was in Mujeres Creando they used to arrest comrades when they did their graffitis, the police would come and put them in the cell. Several comrades knew what it was like to spend a day in prison, but for me it was going to be my first time. They put us on a bus, and I said: “This is it. They’re going to put us in and it’s going to be a day for sure”. We had already prepared for that, you have to know what you’re risking when you do this kind of thing. And I said, if something happens I’m going to call my sister, my mum won’t find out, because if she finds out she’s going to have a fit. They put us on the bus and they went to the middle of nowhere. I said: “But where are they taking us? Why are they taking us?” And they let us out there on a hillside. This is the action I remember most because of that feeling. We were actually very scared because we thought, since the Pope is coming, they are capable of doing something to us, or kidnapping us and not just doing something that is wholly legal.

But the pictures came out. So we said “It’s done”, and nobody else […] that I saw [did something like that during the Pope’s Latin American tour]. It’s not a question of art, for us it’s not a territorial question of occupying the street either, it’s a symbolic question of occupying public space, not so much to vandalize, but to intervene in the discourses of power. That’s why we made an intervention to the statue of Columbus, and to the one of Isabela Católica. We have a Spanish queen [in one of our squares], it doesn’t make any sense.

Anahí: And you renamed that square Plaza de la Chola Globalizada, right? The graffiti is still there.

Danitza: Yes, it has become very interesting. When we turned her into a chola, that photo went everywhere. I’ve never seen a photo of us go so far. It went so far that the Ministry of Depatriarchalisation took the photo for one of their posters. We denounced them on social media and they took it down, but what the fuck is wrong with them? They’re going to repress something and then [they’re going to] use the photo without [giving] us credit? Later, UN Women (it’s colonialism, it’s liberalism) used the photo…

I remember I was at a kind of seminar given by an artist, Rogelio López Cuenca, who was talking a lot about monuments, when they started to bring down the monuments of Columbus and, above all, when the dictator’s head fell in Afghanistan. And he said: “Monuments are [an] extension of the symbolic discourse of power”. That’s why they have such a vertical construction, it is a concept of surveillance reminding you of your place. […]

So intervening is very important, it’s not just a question of vandalism. We have always struggled against those who said: “Don’t destroy public space”. The mayor we have only really thinks about that and the very conservative part of La Paz society, which is always the most elite part, the people who have access to cultural spaces, always says: “Oh no, how can they destroy that? Why are they damaging that? Italy gave us that statue!”. (She laughs) How can you not destroy it?

In all of Mujeres Creando’s interventions their actions have been reversible, using paint that is removable as well as putting clothes on statues, all of which come off easily.

Anahí: Is there any other action that you really enjoyed producing?

Danitza: I can tell you about the Altar Blasfemo (Blasphemosu Altar), [an] action and artistic proposal that was very intense for me. It is a work signed by three people: María Galindo, Danitza Luna, and Esther Argollo. These virgins here [in the dining room of Virgen de los Deseos] were taken from the altar.

In 2016, there was a Biennial in Bolivia. They are very elitist biennials, they invite many foreign and national artists, but they revolve around one person in charge – the curator. María has a trajectory that many elitists here would envy. They say: “Why is an activist going to take up this space?” So, the curator said to María: “Bring one of your works, since you do so much outside, why don’t you bring one of your works here?” She said, “If you want me to participate, then get me a wall near Plaza Murillo, get me the wall of the National Museum of Art or the façade of the vice-presidency building. If you give me that, yes.” She told us and said to me: “I thought they weren’t going to do it, I thought it was like sending them to hell, I mean as if they were going to get the wall of those heritage buildings!” But in the end, she got the wall of the National Museum of Art and María said: “Now we have to do something!”

They were only given two days to paint the wall, in the same week they were running a large feminist gathering, so they were only able to spend a day putting the work together before the opening of the exhibition. They took what they had already developed in the intervention for Papa Francisco, an unholy host, images of Christ carrying a cross made of penises, as well as new interpretations of feminist ‘virgins’, they built around this to make their work “Altar Blasfemo”. The wall they were working on was near Plaza Murillo, where they could once again make demands of both the church and the state.

Danitza: It wasn’t just the altar, it was a critique of the state and the church. We made an altar to the church in our style, and for the state an anti-chauvinist shield. We took the Bolivian coat of arms and transformed it into the worst coat of arms. […] We also created virgins. We decided, the virgins go on top, the Christs go on the bottom and we are also going to include a Pope masturbating. We made the Virgin of Desires, the Virgin of the Ovaries, and the Virgin of Abortion.

It was 24 hours of work between the three of us. It was about eight or nine meters. We told all the women in the movement to come and help, even if it was just to paint a brushstroke. And at night, when we started to see what it was, people came, they called the press, asking: “Who are you and what are you doing? Are you vandalising?”

Anahí: No, it’s art!

Danitza: (Laughs) They had no idea that it was part of a Biennial, that there was a permit. We finished, with all the interruptions, at midnight. The idea was to inaugurate it the next day, the Biennial, in theory, was to be inaugurated at night and María said that we should do an inauguration at ten in the morning, on our own, because those other people didn’t interest us. As if we could have done it! The next day it was scratched up, it said “Fucking Feminazis”, “Locas”, it was all scratched up, and it wasn’t that it had been done in the dark, there were people there at the time doing it. A kind of mass of people started to gather, people from the Church who wanted to set something up. Forget about the inauguration, people wanted to tear down the wall. And the thing that fucked with them the most was the altar. Not even the shield, and the shield was powerful: it was a guy practically clutching the weight of machismo, strapped to his penis. [See more photos of this here]

It was terrible, if there had been stones they would have thrown stones at us, we could have been stoned. The police came to take care of us, a reverse of the usual. I really thought, this is like uncovering the scab and seeing the pus come out. When you make an image, the power of the image generates a social welt that bursts everything and helps you see how sick your society is. I said, is this 2016? It seems like we live in a village in the 1800s and if the priest says burn them, they’re going to burn us. I felt disappointed in the society I live in. But not all the people think like that. Even the curator came out to say congratulations girls, and he went back in (laughs).

Anahi: That’s how they always are: they don’t care about anything.

Danitza: Even the director of the museum, [when] the journalists went to ask him how they had allowed it, he said: “No, they didn’t tell me, I thought it was going to be another work, it’s not my responsibility”. He was a cretin, a real cretin. I already knew that the artistic class was like that.

Following the exhibition, they were commissioned to bring the Altar to an exhibition in Quito (Ecuador), where they were also censored after being placed right on the back of one of the oldest churches in the city. The exhibition was themed around transgressive feminist work titled ‘La intimidad es política’ (Intimacy is political), and they shared a space with the Guerrilla Girls, Yoko Ono, and Marina Abramovic, and work by the Zapatistas.

Anahí: One thing I’ve been working on is the issue of embodying politics. Do you work on something like that? Do you talk about embodiment in your practice?

Danitza: We talk a lot about what it means to ‘poner el cuerpo’ (putting your body, but reads more as putting your body on the line or using your body), it has a lot to do with an ethical principle, among the many that exist in Mujeres Creando, which is to speak in the first person, from your body, from your reality, from what you know and not to speak for third parties, because that also happens in liberal feminism, doesn’t it? Because white women and the liberals want to speak for indigenous people, for the victims. And on the other hand, poner el cuerpo also means going out into the street. Because how are you going to realise what is happening in society if you yourself don’t risk society’s reaction with your own body, with your own voice?

Your body is you and your word. The first action we did on Mother’s Day, at some point we started singing the hymn to the mother and when people realised what it was about, it generated a social reaction and you feel that reaction in you too. You kind of mirror what you are doing. I know this has a lot to do with performance, because it has a similar principle, and sometimes people get confused and think that we are performers.

On one hand, if you want to categorise what we do within the art system, it does fit within [performance]. But on the other hand, what we are doing is not just art. We’re taking a risk, if [doing an] action means something important to me as a person, and something important to the movement and I want to stake my freedom or my physical integrity on that, then estoy poniendo el cuerpo.This is not the same as making a pamphlet, or posting on a social network and seeing what happens… It’s another thing to put your body on the line and put your own voice and your own words at stake, to listen to yourself. Especially if you are a woman in this country, the first thing they teach you is: “shut up, don’t say anything else, don’t be loud, don’t be mouthy”. Taking your own voice is not easy. We still struggle with the process of throwing our voice, and even knowing what we’re going to say.

I don’t think we are closed to being called performers, but on the other hand, we know that what we are doing is not just that and has a lot to do with putting our bodies, above all, on the street. The street as the main stage.

Anahí: There is a double meaning of poner el cuerpo. For example performers, on the one hand put their bodies physically out there, but as you say, there is two layers. You can’t leave the street, in the same way you can leave a performative stage. Not the same thing is at stake.

Danitza: It’s much more controlled, especially since the gallery does that a lot. In other words, if you do a performance in the gallery, how far you want to go is much more controlled. Even the discourse you give in a gallery, one enters a universe in which you know you are dealing with an artistic pause. The public is allowed to for a moment to feel what the artist is going to say, but when they go out into the street they are going to live their reality. They remember the sensation, maybe I will like it, maybe it will mark me, but it’s not the same, it’s different on the street.

We finished the conversation by returning to the role of creativity in political struggle, Danitza’s own journey through this as well as the paths of other compas around her who are working to weave their creative practice into political work. This approach to building a movement continues to stand out in a territory with a strong tradition of mobilizing but with a relatively choreographed way of taking the streets.

Danitza: One slowly understands that there is a creative part to the struggle. Creative work can be a motivation for your political work, but your political work can also feed off your creative work, your political work can have a conceptual base in the creative, and you can play with both… Here in Bolivia there is still a very square discourse of social struggle. That is, to demonstrate means just do the march, go with a banner and do some kind of damage or whatever, and that’s it… That’s the shape social struggle takes on the streets, and it doesn’t have to be that way. For example, I could tell you that many of the current feminist collectives outside of Mujeres Creando hav] taken us as an aesthetic reference, as a strategic reference and as a political reference. So there are already comrades from other collectives who are encouraged to throw paint or do performances in the street.

Speaking to her own practice as an artist, feminist, and activist, and what that means about making interventions in these spaces she says:

Danitza: The etymology of art history is masculine and patriarchal. And there is nothing you can do about it. The idea is not to fix what’s already done, but rather to undo it and strip it bare, to show that it’s wrong. I intend to produce things for myself and for the movement, because I have found that the feminist position that I have discovered here has to come out in some tangible way.

In April 2023 Danitza released the book: ‘Conceptos fundamentales para las luchas feministas’ (Fundamental concepts in feminist struggles), an adaptation of the book ‘Caliban and the Witch’ by Silvia Federicci, featuring Danitza’s illustrations. This book was published by Mujeres Creando.

To read more about Mujeres Creando, listen to their radio and see updates on their work, you can go to their website and Facebook page.

Danitza Luna lives and works in La Paz, Bolivia. Luna is a cartoonist, illustrator and graphic designer, graduated in Visual Arts from the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (Bolivia), specializing in sculpture. Since 2011, she has been part of the anarcho-feminist movement “Mujeres Creando”, one of the most important and influential political platforms in the country, which develops artistic projects and interventions in public spaces, as well as art workshops and educational programs in universities and women’s unions.

Footnotes:

1 Intuitive feminism is a term and approach to feminism used by Mujeres Creando and María Galindo in particular, which returns the power in theory making to “las rebeldes” / the rebels and to sites like the streets, the neighbourhood and the market, it is a bottom up approach to theory and affirms that feminism is something that comes from first hand lived experience, not something made in institutional contexts.

2 Central Obrera Boliviana, Bolivian Workers Centre the biggest trade union federation in Bolivia.

3 Office of the Ombudsman, literally translates to the Defensors of the People, this is an institution that has been established by the constitution to safeguard and fight for the human rights of the country. It is supposed to be independent of the state.

4 Confederación Pueblos Indígenas De Bolivia/Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia.

5 Chola, is a term used for an indigenous woman, one who usually wears traditional clothes. It can be in a derogatory manner, with racist tones.

6 Birlocha is a term used in Bolivia to refer to a woman who is rude, vulgar, crude, a slut. The word’s epistemology goes back to colonial times where it was used to definie indigenous women who dressed as ‘upper class’ or to mestiza women who did not wear formal clothing correctly, removing underskirts etc.

7 Quechua word for baby or child

Main picture credit: Action against Papa Francisco’s Arrival in Bolivia by Mujeres Creando.