Whatever Possessed You To Perform?

29th July 2021By Tuna Erdem & Seda Ergul (Istanbul Queer Art Collective)

This work is part of the performingborders 2021 August newsletter: Shifting Landscapes

ONE:

As a prelude to our musings on the subject of “automation and possession in live art and performance”, which we believe to be radically different from acting proper in film and theatre, let us retell two often quoted notorious anecdotes of Method Acting, which is the method whereby an actor “becomes” the character they are playing, rather than just depicting it.

On the set of the 1976 film Marathon Man, Dustin Hoffman, the method actor, chose to stay awake for three days in a row to be more convincing in the role of the torture victim and upon learning this, his co-star Laurence Olivier asked him: “My dear boy, why don’t you just try acting?” Or so the story goes.

Daniel Day Lewis, another method actor who was already infamous for staying in character even off-camera during his Oscar-winning role in My Left Foot so that he had to be carried around and spoon-fed during the entire shoot, immersed himself in the role of Hamlet, to such a degree that he saw his own father’s (the famous poet Cecil Day Lewis) ghost on stage at the London National Theatre in 1989.

It is no wonder that ghosts enter such stories, since it seems as if the actors are not “playing” a character but are being “possessed” by it. And what is a character but a non-corporeal entity that jumps from body to body to live on and on. Indeed characters such as Hamlet, that have outlived generations of actors, can be seen as body-snatching demons.

It is tempting to speculate that these stories would not be in circulation if they had happened nowadays. “Acting” is not a “becoming” but a pretending and in the ideological climate of the contemporary moment, there is something very pretentious, even insulting in the notion that one can ‘know’ what it feels like to be in a position of being discriminated against, by simply training for that position or spending some time “passing as if” you were in that position. Contemporary sensibilities would often go further and demand that only people who have already gone through the experience for real, should be cast in the role in question: a disabled actor for the role of a disabled character, someone with real sex work experience for the role of a prostitute, etc. Though the role of a torture victim being played by a torture survivor, might pose another problem of triggering trauma and turning acting itself, into a torturous experience. So asking for the actor and the character to coincide in reality, is still, in line with assuming acting has to have a dimension of reality. A point Laurence Olivier would still find baffling.

However live art performance rarely has anything to do with this immersion into character, in scripted feature films or theatre plays or the very complex relation between reality and representation, becoming and pretending, experience and appearance. Performance art has no character to become, to stay in, to pretend to be and it has no rehearsal or retakes to perfect the act. Most of what is known as performance art, is nothing other than the artists as their naked self, putting themselves through a real experience that is not scripted and very loosely controlled, if at all. Usually there are merely some limits in place and the rest is left to the happenstance of the “here and now” or “chance operations” and very open to the energy in the room or the intervention of the passerby.

Despite this difference performance art creates its own legendary anecdotes, very similar to the ones retold above, as is the case with many notorious anecdotes of Marina Abramović, the ‘grandmother’ of performance art:

In her performance Rhythm 0, she invites the spectators to use the 72 objects she has provided on her naked body. Some audience members took the instruction to the point of whipping, cutting and holding a loaded gun to her head. After she stood motionless for six hours, the protective audience members insisted the performance be stopped, seeing that others were becoming increasingly violent.

During her performance Rhythm 5, she created a star shape with wood shavings covered in gasoline and lit the wood on fire. After cutting her nails and hair and dropping them into the fire, she lay down within the burning star. When audience members realised her clothes were on fire and she had lost consciousness due to the lack of oxygen amidst the flames, they pulled her out, ending the performance.

In the 1975 performance of Lips of Thomas, she whips and cuts herself then lies on a block of ice and starts to freeze. After 30 minutes on the ice block, the artist was carried away by members of the audience, who cannot stand the situation any longer.

Although in the method acting anecdotes the actors seems to be trying to assert maximum control over their own acting and in the anecdotes of Abramović, she seems to be relinquishing all control to the spectator, the reason these stories become so cherished and hashtagged and reposted is because of the extremes that the performer/actor is going to.

In each case, when you listen to the story you cannot help but wonder: whatever possessed these people to do such things? Which is not a bad question if you really try to find an answer beyond “they must be crazy”. Endurance performance, as well as most forms of body art, have such an impact because of what is regarded as their masochistic excess. In this sense, Hoffman, Day Lewis, Abromovich can all be regarded to be torturing themselves in the name of art.

This “crazily dangerous” aspect brings the performers on both sides, closer to that of the circus act, of the spectacle of impossibly dangerous acrobatics and near death experiences. But then again, most of those are just smoke and mirrors and not at all the real thing, so here we go again, unable to distinguish the real from the not so real. No wonder the notion of the supernatural, of demons and possessions are at work here.

TWO:

The excess, is exceeding the real as in surreal

the conscious as in unconscious,

the normal as in queer.

But of course it is old as hell to believe artists are both a bit crazy and have a special pipeline to the divine; that inspiration is sent from above;

that creation comes from the gods,

therefore the artist

in times of creation

must be possessed by a divine force;

that, conception of new things can only come about by the penetration of the Holy Spirit or Zeus in the form of a golden shower. All very creative fictions, enduring and insistent.

And a load of bollocks.

We don’t believe in the artists as the chosen one, we don’t even believe in talent. No doubt some things come more easily to some than others but that is just a tiny ingredient in the soup that is art. We do not believe that the artist is any crazier than the next person. And we believe in the sentence Louise Bourgeois, wrote and stitched and engraved over and over again:

Art is a Guaranty of Sanity.

We believe that art is a thoroughly human exercise, that everyone needs. Art, is a human right. Not just consuming it, but creating it. Just as sports, is a need and a right and a must to keep sanity, so is creating art. But although the world has acknowledged the need to exercise the body, opening gyms in every neighborhood, for some reason, we have failed to acknowledge the need to exercise the soul and think the studio is reserved for those who are dedicated Olympians.

We don’t believe in a unified self, we believe in the unconscious, that human beings only partially know what they are doing and even less still, why they are doing it. That, there are conflicting forces and cacophony of voices living inside each and every one of us.

We become someone else when

we are with different people,

And on different occasions;

We have different personas

to face different situations:

I am panicky in daily life but become calm and collected in life-threatening extraordinary situations, you are rather meek in dating but become dominant in bed, they are a loyal friend, but a competitive enemy at work etc. And these different “characters” don’t just come in pairs or neatly organised in dichotomies. We wear our characters, like we wear our costumes: a different style for different occasions, as well as for different eras of our life. And yes, sometimes “the suits wear us,” but if we are then possessed, it is not by a magical suit of armour or even the poisoned dress of Medea, it is by a part of ourselves that we neglected or repressed or simply couldn’t find a use for.

We also know by first hand experience how you are made to fit in a role by parents, by careers, by well meaning friends, by lovers, by community. How subtle and insistently, your roles are tweaked constantly to fit into the expectations, norms, preferences of others, how you are given scripts and mentors and guidance and endless policing, for so many of the roles that you are forced to perform. You are made to perform under threat of exclusion, you are made to lie on the torturous bed of Procrustes, as a life long endurance performance. After all, it has been more than 30 years since Judith Butler tried to explain that gender is a performance we repeat every day, every second.

So performance art creates situations in which personas that have nowhere else to manifest, emerge. It is healthy, not crazy and it is not the exclusive domain of some special godlike, talented people.

Human beings are already possessed,

because they possess an unconscious,

performance is an exorcism.

THREE:

The appeal of possession, is no doubt connected to freeing yourself from responsibility, being able to claim: “it was not me! I was possessed!” Or “It was beyond my control” as it is famously repeated in Dangerous Liaisons and should remind us that extreme emotion is always a form of possession, in which control is lost and the demons that possess us are indeed nothing but unconscious traumas. Freud famously said that ‘there is no original trauma’ and that trauma is activated only when it is repeated.

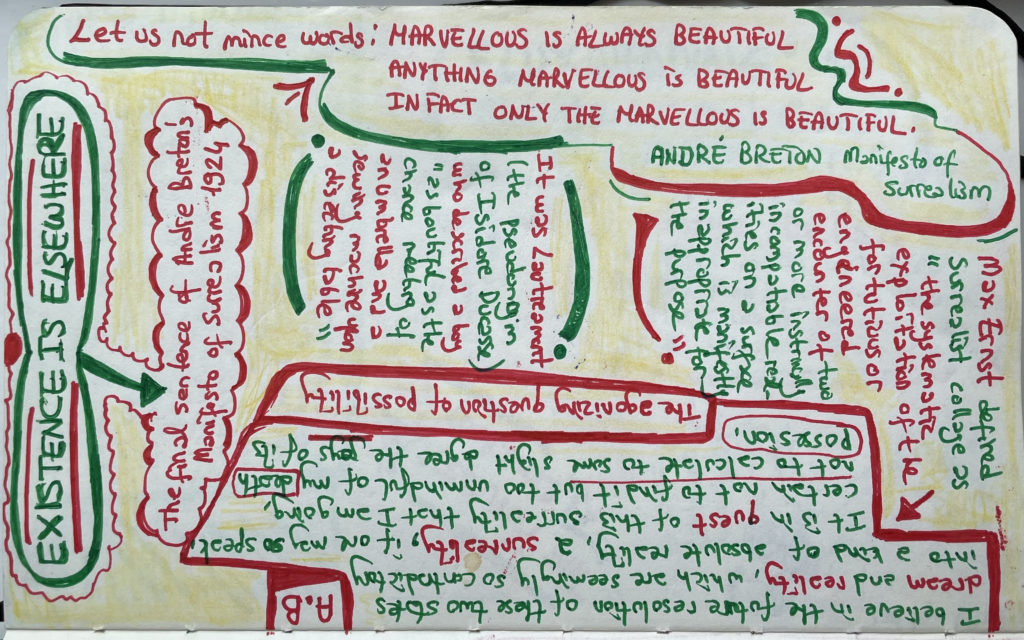

The automatic writing of Breton and the surrealists is like a spell to invite possession, an avant-garde method of creation, but unlike The Method, as method acting is often called, it can easily be done by anyone, that is why today it has turned into a method used in any type of creative workshop. There is of course something naive in its original conception, so much so as it assumes the conscious and the unconscious can be separated, that you can find a technique to bypass the conscious and have direct access to the unconscious (even if we put aside the questionable desirability of such an endeavour). In fact, these two are like a moebius strip, as Lacan has asserted, it is impossible to know where one ends and the other begins, there is the unconscious present in every so called conscious act and the unconscious has its conscious shadow trailing along, even in the pitch dark of repression.

Automatic writing is, free association as a technique of psychoanalysis, turned into a technique of writing and creating. But whence it was the gods that talked through the artist, now it is the unconscious that talks through them, always rendering the artist itself a mere mouthpiece, a passive conduit from another realm. However, unlike the gods from above, that only speak to the chosen one, the demons from within are the human condition itself. That is why it can be used by anyone, whether they possess talent or not, because it lifts the pressure of responsibility and the paralysing dictum of perfection. Making mistakes is the whole point of the endeavour after all and as such, it is akin to the Queer Art of Failure as proposed by Jack Halberstam that we embrace in our own art as Istanbul Queer Art Collective.

If Homer was the mouthpiece of Olympus, then Breton was the mouthpiece of Hades. But strangely enough, there is nothing dark in Breton after all but merely fantastical and comical. In fact in the very moment of finding this technique, he placates our fears, rather than expressing them since he explains that the image of a man cut in half, which could have been straight out of a horror movie, is in fact nothing other than a man leaning on a windowsill.

I guess one should never forget the “live”, performative aspect of the technique of free association in psychoanalysis: that you free associate to a therapist, which is a very specific audience. In this sense, it should be underlined that Breton’s first experiment with automatic writing was not done alone, but with a fellow artist that created a countertransference almost immediately.

There is no real free association without transference and it is not free association that is the possession, but precisely transference and countertransference: the projection of the others, of imagos of The Other, on to the person of the therapist. You are able to free associate when the silent subject who is supposed to know is possessed by the imago, the unconscious image of your M(other). Projecting your possessions on to the other, is what frees you to associate freely, not being possessed by the unconscious but by creating some free space in there through temporarily bringing some of it outside.

And of course there is no performance, no live art, without an audience.

There is this theme often repeated in fantastic plots of demon possession, whereby exorcism is only possible if another host body takes the demon in, when it is taken out of the possessed. In the most famous of these plots, the film Exorcist the priest saves the teenage girl Regan from possession, by inviting the demon into himself and then committing suicide. In a more recent twist in Buffy the Vampire Slayer the possessing demon is tricked and transferred into “the vampire without a soul” Angel, where it withers and dies. But this storyline already proposes that the soul is a possession, in the double meaning of “owning” and taking hold of you. People ask “whatever possessed you to do these things” to Angel, when he losses his soul, not when he is in possession of it.

FOUR:

Repetition is the key that binds these desperate musings together. Repetition as a technique to welcome slips of tongue, pretty much like automatic writing welcomes free association. The flow of repetition is like a contradiction in terms; to repeat feels like staying in place, a damn in front of the flow; but insistent repetition puts a magnifying glass that lets you see you can never stay in place, you can never even repeat exactly, change is always there and never as obviously as when you repeat insistently.

As any child would know,

repetition also hallows out the meaning of words, drains them of their precarious certainty, distorts and mocks them.

And as any self-respecting minimalist avant-garde artist would know,

repetition is a tool that enables one to detect even the smallest differences in what would have passed as sameness.

FOUR one:

SOUTH: The Border Oath Version

Performed at: Sound Acts, Athens, 06.05.2016

Performers: Seda Ergul, Leman Sevda Darıcıoğlu, Tuna Erdem

In the Fluxus performance score “SOUTH no.3”, Takehisa Kosugi asks the performers to turn the word “South” into sounds, by pronouncing every syllable and letter in every combination possible.

In remaking SOUTH, we replace the word “South” with a specific text: the military oath Turkish soldiers are obliged to take each and every time they start their border watch duty.

The oath is like a charm that creates the very concepts of land and nation via repetition. Repetition is what creates this imaginary community. And imaginary community is the name Benedict Anderson gives to all nations. Indeed this is how the notion of nation is drilled into the members of any nation, not just Turkey.

As woman and queers doubly exempt from military duty, our method, was to repeat the oath over and over again and in a way this mimics the repetition of the text by the soldiers. However, by opening ourselves to free associations, every time we repeated the text, we created a different version of it, we turned Turkish into gibberish and accentuated the possible different combinations and hidden phrases to be found using the same letters and syllables within the oath, to create a counterpoint to what it is trying to say.

In fact our aim was to steer away from the inherent stability of language, toward the unstable, performative, immediate, humorous and playful world of sounds, and by doing so, to call into question the inherent stability of the physical borders and the conceptual foundations that lie behind our need for them.

FOUR two:

Evil Tongues, Evil Eyes

Performed at: Deep Trash Underworld, London, 2017

Performers: Tuna Erdem, Seda Ergul

The popular imagery, both possession and spell casting usually involves a “foreign” language: a dead language like Latin or an Eastern-sounding language like Turkish. This is not limited to representation either. For instance in Turkey, spells are written and spoken in Arabic, a language most Turks don’t know. Arabic words also cast a “Muslim sound” to what are, in most incidences, pagan rituals predating Islam. It seems that in the realm of the occult, “speaking in tongues” symbolises both our inherent fear of foreign cultures and our attempts at bridging this cultural gap.

In this spoken word performance, we articulated a text consisting of Turkish colloquial phrases used against “the evil eye” and an ancient Assyrian spell. We repeated the phrases 40 times, which in Turkey is believed to be the number of repetitions necessary for a phrase to attain supernatural powers. As we repeat the words we literalised some of the phrases, by using skewers to stab 40 “eyes”.

The evil eye, which is the gaze of the envious, is the most dreaded supernatural force in Turkey, as in many other cultures. In articulating the spells against the envious gaze using Turkish as a foreign language at a time when the English have chosen to leave the European Union to prevent the envious Turks from flooding their country, we hoped to try a bridge/bewitch, the underlying cultural gap.

FOUR three:

DadaAda: 4 poems of The Baroness at 1 of the Prince Islands

Performed: In front of Prinkipo Greek Orphanage, Istanbul, 2015

Performers: Tuna Erdem, Seda Ergul, Leman Sevda Darıcıoğlu, Onur Gökhan Gökçek

https://fytini.bandcamp.com/track/dadaada-4-poems-of-the-baroness-at-1-of-the-princes-islands

Live recording for the album Holding Tail With Mouth: Poems by The Baroness by Φυτίνη/Fytini in commemoration of the 100th year of Dada, which we turned into a performance because we can’t just record, we have to perform. The place is in front of the ruins of the Prinkipo Greek Orphanage in Buyukada, which is one of the biggest wooden buildings ever built and was seized by the Turkish state from its rightful owner the Ecumenical Patriarchate and left to decompose. We “read” four poems by the Dadaist poet Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven aka “The Baroness”. Poems: To Home, Fix, To Whom it May Concern, Perspective.

The poems in question were Dadaist, surrealist poems. They are by a very important figure of the Dadaist movement, who alas never became as famous as her male counterparts. In fact, there are rumours that Duchamp stole her ideas as his own. We read them by repeating words and syllables over and over and on top of each other. We were a chorus of repetition, allowing the text to possess us and carry us to places we did not decide in advance, letting it flow through us. We were already “talking in tongues” since English, the language in which the poems were written was not our mother tongue. Some of us didn’t even know English. The fact that we performed in front of a building that seemed too big to ignore although it had been ignored for decades, precisely because in it, Greek was the language used instead of the ‘official language’ of Turkish, felt like conversing with the ghosts of this haunted house. Repeating words until they lose their original meanings is casting a spell that asks the ghosts of a violent history to come forward and talk through us and to us. The fact that the performance happened a day after State of Emergency was declared, due to an attempted military coup, was what bridged the repressed violence of old, with the unarticulated violence of the present, on a calm and serene hilltop. The ghost of the Baroness and her stolen ideas joined the chorus, from the other side of the world as well as the grave.

NINE:

The beginning of every life, the first period of every life, -to which the memory can’t reach out, because it doesn’t yet possess the tools of this reaching out-, is constructed by the other’s language. This is a story from such a time, that my mother told me repeatedly: One day, when I was younger than 1, while I was sitting in my highchair and my mom’s back was turned to me, I had called her by her name and asked her to give me water: “Oya bu ver”. This was the first time she heard me speaking. She laughs every time she tells this story. “Darling” she says to me, “I thought you were possessed”. She tells a story of celebration, I hear a story of horror.

Istanbul Queer Art Collective was founded in 2012 to engage in live art, with a view that the documentation of performance is an art form in itself. The collective is currently based in London and is comprised of its two founding members Tuna Erdem and Seda Ergul, who are firm believers in what Jack Halberstam calls the “queer art of failure” and what Renate Lorenz calls “radical drag”. Their performances range from the durational to the intimate and can morph towards other forms like sound art or installation. IQAC has performed at various art events around the world among which are: House of Wisdom Exhibition in Amsterdam and Nottingham; If Independent Film Festival and Mamut Art Fair in Istanbul, Athens Sound Acts Festival in Greece, Zürcher Theatre Spektakel and Les Belles de Nuit in Zurich and Deep Trash, Queer Migrant Takeover and NSA: Queer Salon in London.

This commissioned reflective piece is part of performingborders’ ongoing conversation with the Performance, Possession & Automation project, funded by Arts Council England and by Queen Mary University of London’s Humanities and Social Sciences Collaboration Fund. For more about this project go to www.possessionautomation.co.uk

Featured image credits: Doodle Quote by Tuna Erdem 2011