Shifting Landscapes: On temporalities and process of transformation | Dinis Machado

14th August 2021This work is part of the performingborders 2021 August newsletter: Shifting Landscapes

Dinis Machado is a choreographer whose work is of outstanding beauty. A balancing act between delicate and harsh realities that occupy spaces of wonder and intrigue, inviting the spectator to become an explorer in Dinis’ ruminations on their own place in the world.

As an artist, Dinis exists and works between Sweden, Portugal and the UK, three very distinct and almost consequential contexts where they found pockets of distinct ways of engaging in their own practice, their own body and transnational understandings of contextualisation of one’s own work.

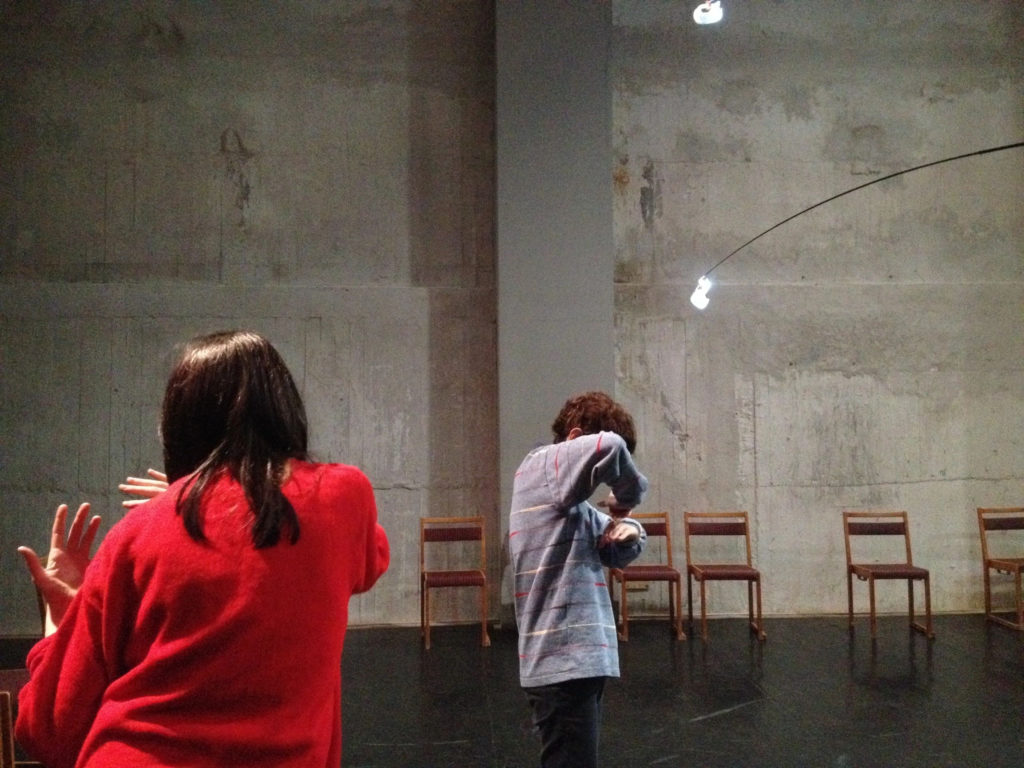

This year, on the occasion of visiting my former home town and region of Coimbra, Portugal, I saw a performance of their latest solo work ‘Yellow Puzzle Horse’ at the experimental performing arts festival CITEMOR, itself a festival that functions as a home for many artists from across the country and the overall Iberia Peninsula (and when money allows, from around the world).

It is with this in mind, and with performingborders’ own research around linguistic and cultural borders, that we have a conversation about Dinis’ trajectories – both personal and artistic – and debate what it is to work across borders, across genders and languages and how those impact our own understanding of ourselves and our practices.

The interview is presented in almost verbatim, with pauses, ‘erms’ ‘ugh’ and all, for we feel these are elements fundamental to understanding the meaning of the conversation. We are two migrants in the middle of linguistic fluxes, constantly navigating the various structures of the languages we employ in dialogue and constantly adapting our ways of communicating to others. So our sentences are weird and sometimes nonsensical, sometimes in what the English call ‘broken English’, and sometimes with straight up ‘made up words’ too. But if you read them again, and embed yourself in the conversation, you will find their own meaning and structures. Whilst this might provide a bit more of patience from the reader, we hope that you come with us on this journey and take your time to understand the sentences even when they might not make much sense at first reading, or they might sound grammatically disjointed. For they are not actually disjointed, but simply consequences of two people navigating their own unique ways of talking to each other, about themselves.

performingborders (Xavier de Sousa): One of the things that we kind of really focusing on at the moment is language and how our own language and our own bodies, our own culture and our own understanding of ourselves is interpreted by those who receive what we put out there from different borders, but also kind of point of view and how that might impact our thinking as artists and insecurities and as a platform and I suppose caretakers. We try not to call ourselves directors anymore. We don’t like it. We prefer to have a bit more of a loose kind of structure for the way, you know. And so I wanted to kind of chat with you as, as an artist, you kind of trade between performance art and choreography and the dance spaces across three countries: Portugal, UK and Sweden.

Dinis Machado: Exactly. Then I tour in others. I mean, I used to tour in other places before Corona, but now much more like episodically. Yeah, there is a bit of a, I mean there is a bit of a fourth center of touring for me. That is South America in general. But it’s like it’s not really a country, it’s just a nucleus of performing arts festivals in South America. But that’s completely stopped now with Corona. Yeah, I don’t know. I don’t I haven’t been really looking into it because it has been it’s already so chaotic to tour within Europe at the moment.

performingborders (Xavier): Could you talk a little bit about your trajectory between you and Portugal, you in the UK and you in Sweden, for instance? They’ll be quite nice.

Dinis: I mean, I’m born in port, in Porto, in the north, and. And I started studying dance and theater very early, like I watched a performance when I was six years old, and then I was nagging my mother to study theater and dance per year. I started studying dance when I was six in 94, so by the end of the 90s I was on my teenager years and this was also the end of the 90s and beginning of the 2000s, as I understand backwards, it was quite a moment of explosion of the independent scene in Portugal, or at least a very strong moment. I did work with the company of Balleteatro in Portugal in the very beginning as a kid – so ‘not for kids’ performances, but as a child actor within strange contemporary pieces. And then I studied theater in Porto, but then when I was 18, I move to go to Lisbon. There was also this thing that I studied mostly I like I studied dance theater, but I studied mostly dance until I was 15. And then when I was 15, I had a bit of a crisis with dance and I shifted completely to theater. So my BA is a BA in theater in Lisbon. And then after that, I kind of, I I studied a bit of visual arts in between, and then I went back to study Choreography in my Masters in Stockholm, but I did start to produce work much like I moved to Lisbon when I was 18. And when I was 20, I kind of opened a company and I started producing work and I produced work regularly until 2012 in Portugal. I worked with several companies in the beginning as a freelance performer and I think I had an encounter that was very important in Lisbon with a company that is called the Cão Solteiro with whom I was like a resident performer for a year and erm… Then I started producing my own work, and that kind of took all of my time quite soon, but, um, yeah, I produced work for seven years or for five years in Portugal before I left. I left 2012. And then, um, I passed shortly in Berlin. And I went to Stockholm to, to, to take my MA but I don’t know, I mean, I never – back then I worked my works were really text heavy, so I really didn’t want to move. I was very scared of it. My English was really bad and, um… But I mean, during these years of the (financial) crisis, it was like one day I was there, but no one else was because everyone kind of moved somewhere. Oh, so at a certain point, I kind of understood that. It was also like – I think it was 2000. Yeah. It was like 2011 that I had super much work and then it was like a cliff… the Ministry of Culture was extinguished… Funding, like a lot of funding was suspended and stuff so I decided to leave, but I really wanted to leave with a context, like I didn’t want to, like, arrive somewhere on my own. So I started looking for a Masters and, to be honest, I didn’t know so much about the Swedish scene back then. I applied for three masters and I stayed in Stockholm and I decided to just go and originally it was just like I was just passing by for the first year, I was kind of discovering where I wanted to go. But I think that very early, as I told you, I was working because I got a residency grant in Berlin just before I start to the master. So I already knew that I was going to Sweden, but I am I was for a while in Berlin, and I think that time was very like I think Berlin was very inspiring, a lot of weight. And I think I also really understood that I didn’t want to live there.

performingborders (Xavier): You’re the only person who ever said that to me (laughs)…

Dinis: (laughs) I mean, I didn’t grow up in a big city I grew up in what is like the biggest city in Portugal, which is pretty small and um, and in the nineties, it was even smaller, so… I don’t know, I always felt very overwhelmed with this feeling of the capital that you need to be the hottest, the coolest, the… I don’t know, I was like… I don’t know, I just understood that was not my space, I think… I think I like to inhabit a space that is a bit less pressured. I’m in general into something that is a bit more calm and slow cooking, so I really ended up liking Stockholm very fast because it is a big city. It’s a lot of cultural stuff going on, but it has also a lot of problems. But it’s also a very peripheric city. And I really like that… Like prophetic in the sense or in the sense that is not in the center of Europe is not a place where people pass by on the way to somewhere else. It’s a place that everyone hates. Everyone thinks the weather is trash. And and I love that. And there are other things that I like also because it’s… Yeah, I mean, obviously in Sweden, people think that the funding structures have a lot of problems and they have. But I think in comparison with the rest of Europe, there is still a lot of space for research and for for things that are a little bit less intensely direct to production. So yeah, this was a bit of fastforward because my relation with the UK kind of happened in the limbo in between Portugal and Sweden because. When you’re studying in Sweden, you can’t really apply for funding, so I had this period when I was studying that I really didn’t had any way to fund my work because Portugal would like, this was when the Ministry of Culture was extinct. There was some years that they didn’t even open like Project Grants. And in Sweden, I couldn’t apply and also like I didn’t and nobody knew me until then because, I produced work that was quite heavy, and I mostly toured within Portugal until 2012… So during this kind of space of time while I was studying and that started a bit before when I was about to go to study, I had this project that was called Black Cats Can See in the Dark But Are Not Seen that I was developing, and one of the partners was Dance4 because I had been there while I was assistant of Miguel Pereira and they really liked me or I don’t know, the way I worked. So we started a conversation and they were supposedly partners of this project, and this project kept being postponed because there was no funding. Funding was like disappearing. So all of that all like we would rescheduled and it would be just postponed. At the time, the Arts Council England used to have at least this policy that foreign artists could apply for funding as soon as the activities were happening within the UK, which I think it’s actually pretty radical, I would say, and pretty unique in Europe, that it’s like what counts is that the activity is happening in the UK and engaging artists in the UK It’s not so much that the choreographer applying is from the UK So we were just looking for possible funding for the project and they proposed that we would put in place the project there and we got the funding, and that was really important because that was the first project that I developed within a kind of international setting. I mean it it was a project that started really in the dark, but it ended up being called for ImPulsTanz, which was like a really big push on an international level. And then slowly, I, I, I finished my Masters in Sweden and started getting more established in Sweden. So our days. Yeah. So my work just kind of kept being structured by these three places where because I then I kept having fun being in the UK because I thought that was a group work that involved a lot of people. So there was a lot of connections that kind of self-generated the other projects and stuff. So after that, I kind of had these three networks in Portugal and Sweden and in the UK that have been just growing since then. So, yeah, sometimes the more difficult one is actually the Portugal one, with more closed doors. Yeah, I don’t know… I think now it’s in a very good phase. I think there is a lot of renovation also in the curatorial tissue. I had a few venues and festivals with whom I collaborated very frequently. One of them is CITEMOR and the other one is the ZDB but Portugal was very arid at a certain point. And I think that Portugal is a very resistant to support young artists or younger artists, and I think there is a big, big deficit of artists from my generation being supported in Portugal, this ‘artist that left the country’ thing… I really think that it’s very it’s a very big… I don’t know the other countries that I have been, and when I am in festivals, I see so much more work from young people being invested. I feel in Portugal you need to prove a lot to get a little bit of money to do something. This creates a landscape that is very harsh, I think, where people have to really create work with no means until they they have any means. And I think that’s a very problematic… Laboural… how do you say like… labour context?…

performingborders (Xavier): Labourious as a context.

Dinis: Yeah. Yeah, yes. I don’t know… My connections to Portugal, I think, are very much booming at the moment and also the UK, I thought it was going to just collapse due to Brexit. But the truth is that I’ve been there more and more, and the plan is that I will be doing quite a lot of projects there. So I’m kind of divided in between these three places. What is not always easy in terms of because all funding is structured in such a nationalistic way and actually I had some luck in the last year, so I had some quite deep conversations about this with some curators of things that I applied for and that people really like, in a very open way, ‘OK, can you explain this? Where are you?’ And when you start trying to apply for funding that is about stretching, or the structuring a program of activities rather than a production it becomes it’s very based on ‘we are funding our artists’ and in that sense, I am an artist in Sweden. I live in a generation that didn’t have the privilege of being able to live in a place. I think sometimes I hear really deppreciative terms about this, what some people call the residency hoppers and people should actually understand that we live in a structure that is presented to us, like it’s not a choice. I mean this is my story of life. I had to leave my country and I had to produce work in a way that I had, and this produced this network of collaborations that is the one that I have and I can’t just erase my life because that that will just put me, like in a negative place that’s asking me to forget about 10 years of networking and production of resources and contacts and relationships and knowledge. But it’s always kind of a struggle on how to how to make how to frame things in a way that that is understandable.

performingborders (Xavier): That is very daunting. Could you reflect a little bit about the fact that when you were living in Portugal and were kind of operating primarily in Portugal before you had to move to Stockholm. You mentioned that your work is very text heavy and then you kind of felt reticent about that, about moving abroad when your work was so text heavy. I was thinking also about like how difficult that makes for you to operate, as you were saying… Could you talk a little bit about that process of adapting your work in a way that becomes less text heavy, per say?

Dinis: It was not that, I think that the thing was the other way around, like when I decided to move from Portugal, I had given up a text or I was in another relationship with text. I mean, I’m saying this, but ‘Black Cats’ is a super text-heavy piece (laughs) I think I had this idea that I was going to be less centered on text because I think around the time I also started really thinking. I think that was a really big turning point in my work in general, I started really questioning, I started really re-articulating the way I think about my work and… Because I think until then I was articulating my work – because I mean, I grew up… Ah… In… when I was 18, we were really living this most also in Portugal at least a lot, this kind of conceptual paradigm. The years that preceded me leaving Portugal, I had to really question this, I mean, I was articulating my first works, I would talk on it through conceptual perspective but actually the works were super fictional. I mean, when you produce work through the years, you articulate yourself better; And I was really into going back to to the body as a matter, as a material, in a very material way… So there was a very big shift in terms of where I was constantly sourcing my material and I mean, that was the moment when I decided to also kind of transition myself.

I mean, I was only a kind of an OVNI (alien) in the theater context because my works were super abstract. They didn’t relate so much with the theater texts in that sense and they were very choreographical back then. I was mostly working around like construction of spaces and things a lot… so my work was very scenography heavy, and there were super many things. I think that was actually more of a condition when I left Portugal, that I really had to restructure the way that I built scenography so that I could tour in Portugal. I toured with trucks l- not with trucks, but like with vans. Um… Yeah, so I think it was a bit the opposite is that I, I kind of… I was in the moment already was where I was looking to get into the body as a material or as a primary material rather than… Rather than starting on the table with text. So like the body, the experience of the body and ‘Black Cats…’ is exactly that. It’s the work that kind of envelops from the experience of moving. There is all these texts that are kind of a fictional diary, but then there is also a lot of very, very bodily material that relates to the experience of the body. Mm hmm. Um… So, yeah, I don’t – I think more I decided to move because I felt I could that I was not dependent on… on text in my work. I don’t know… everything… I mean, sometimes life is like that. Several things come together, in the moment that is possible…

performingborders (Xavier): Yeah, of course. Yeah. It’s interesting, that, because it kind of speaks to this kind of like… Well, there was this necessity for you to move, right, in your life because of structures failing around you of support, but at the same time you were kind of met in this moment where you were going through a transformation of your practice anyway, so that allowed you to travel more freely. But in the way, can you talk a little bit about the frame in your work across borders that you were kind of referring to earlier and how? Perhaps how, how do you see your work being framed or read differently across the places that you kind of operate in?

Dinis: It’s very hilarious, because my work – I think my work is considered a very formalist work in Portugal and it’s considered extremely theatrical in Sweden… like this in very mainstream terms. I think this has very much to do with the traditions of a rich country, like because Portugal has such a strong interdisciplinarity tradition. I feel whilst in Sweden it’s much more divided, like what is dance and what is theater and… and then in the UK!… I don’t know, I would always like… I remember that when I started working in the UK, everyone was like ‘oh, the UK…’ because everyone has this terrible idea about the UK dance scene… And I think it took me some years to understand what was going on there. Why were people even interested in my work in the UK? But I mean, one of the things that I understood is that it is very difficult for the UK artists to tour internationally… And… And I think that was that is also, like on an institutional level, that is also something that is very appreciated in my work that I have collaborated with UK artists and take them to international context. But…. I don’t know, I actually really I like more and more the scene in London, I would say, because I think you have this super mainstream scene that is the one that manages to tour internationally and etc. But then you have to really like… I don’t know… like the dark side of London. (laughs)

performingborders (Xavier): What do mean about the dark side? (laughs)

Dinis: All of them! No, I don’t like… I think the UK is one of the places that has I mean, for the good and for the bad, where diversity questions are think – are thought on a super consequent way. It’s also the way where people are empowered, like what’s in the rest of Europe. I feel that disabled people, trans people are so often still in a place where they have to kind of beg for a place or something. You will always have a cis able white person telling you what’s OK, what is not OK. In the UK, they will just slap in their face and say ‘no, this is what am going to do’. And I love that. Like, I like that there is a really strong community. I mean, it’s like it’s not one disabled person dancing or I know in Sweden is also not one, but it’s like five or six or ten. I mean I’m talking like that are in the circles that live professional from it. I think, yeah, I really like that about the UK. I also really like that is, I don’t know, the UK is this place… It’s like I spend there quite some time per year but I don’t live there and I love that. It’s like I fly, I go to a very big city for a while and I’m constantly in touch with the UK, but I think I would never manage to live in London. It’s like it’s so much, I feel like a kid.

But I don’t know, I think I… Because I mean, what what everyone would basically tell me is that… Is that the UK is stuck with a kind of a generic or generic modernist style or kind of thing. And I think there is – I mean, I have seen that also a lot, but then there is… I think it’s very plural, like the fabric of London, like people have really different gazes. They have their own thing that they’re into, and then they will look at your work through their own paranoias. I really like that, that it’s a bit… I feel the gaze over my work is very – it’s multiple… Like, it’s not that there is like one way of looking at work and people. I mean, I also only perform in the more on the side places of London that where there’s probably all the weird people that are the ones that I love. Yeah, I know, but I mean this just to say that I think I think, like, there is a predominant gaze over my work in Portugal, the predominant gaze from my work in Sweden. But in the UK, it’s a bit more strange. But I also think the gaze over my work in Portugal is changing a lot. I think for a while people were really not getting what I was busy with and they just assumed it was badly done. I mean, maybe it is! I don’t know… but I think there is more and more people kind of relating to what I am doing. For example, this work that I showed now within ‘Pê de Dança’ in Lisbon, I presented that same work in Portugal in 2014, I think… and back then, I really felt that people were like, ‘what the fuck is this’? But now we re-staged that work with local performers and I think the work was quite well received. So I think there is a very different gaze over the work.

performingborders (Xavier): You talk very much about you in your work about temporalities and spaces that you inhabit.

Dinis: what was the first thing that you said?

performingborders (Xavier): Temporailities. Yeah. And just the copies that I’ve seen and kind of things I’ve read. But also hearing you talk about this kind of inhabiting different spaces for temporal… for a short amount of time, in a way. And so with that with that kind of temporality in mind, I wonder if you can reflect a little bit about how that piece, the differences of how that piece was received in both times.

Dinis: Wow. That’s a lot to answer. I mean, a piece in particular is ‘Cyborg Sundays’ is a piece where there is a story, there is a description of… I mean, it’s a piece that is working very much about my moving from Portugal. And it’s a piece where there is a description of a group of people that live in a self managed community in a desert island, and it’s just a description, a very detailed description of all the gestures that they do during a day. So it’s just like they picked up a glass and they put it there. And there is a kind of… Ideallic tone of it, it’s like vaguely vanilla and… It’s very detailed and the story, it’s made with five performers and the performers, they don’t know the story by heart. They just know like in very detail of what happened there. So during the performance, they try to – they try to recollect this memory together, but they don’t have, like, memorized sentences like in theater. They will just like, oh, someone picks up the glass and then someone else will… And they drank the glass slowly… And so they’re just like trying to reconfigure, or recollect this memory. Somehow, throughout the process of rehearsing the work, they have to kind of created some sort of prosthetic memory, so they, they kind of feel that they have been in this place.

And then in parallel to this, they are dealing with a series of.. of movement practices that relates with gestures. I mean, it’s a very complex network where they are both building and constructing movement at the same time. And it’s also kind of a trance-like because they have so many tasks that they have to deal at the same time that it produces a kind of a slowness that is not really slow is just that they are administrating all these things at the same time and it produces some sort of trance-like experience, I would say. And for the viewer, what it produces somehow is that these gestures that are like… they are clearly gestures and they’re very precise, like you kind of see that they are not like just improvising, that they are clearly doing something but you don’t really have a name for it. It’s pretty abstract, but it’s always gestures, it’s not just movement. So these gestures kind of work as vases for these things that are being described, it’s like they are not illustrating these actions that are being described, but they kind of give them flesh in a very abstract manner. So, yeah, I mean, that work is all about the things that you were saying, like you said, temporality and – what was the other?

performingborders (Xavier): …the islands that you are referring to, right?

Dinis: Yeah. Yeah. So, I mean… My work is very much in very different ways about this idea of like consubstantiating fictions, like how do fictions transform our bodies, how the way that we see things transform our bodies in very material ways. But all in all, yeah, I mean, the reverse of it, I think it would be how we… how we kind of have different experiences of the materiality of our bodies in different contexts. I mean, this put to kids would be like… How we kind of imagine our bodies differently when we are with different people or in different places or the kind of intangibility of trying to grasp the shape of our body and how it works, how it looks. And obviously, this has strong connections with trans questions as well. Yeah… And with that kind of… also…. kind of mutability of the body in itself, like, I don’t know, for one side, I work with transforming the body, transforming the architecture of the body. Like, I don’t know, I have pieces where I have this foam bricks and they’re one of my feet so that it very concretely kind of transforms the whole architecture of my body. I mean, this is a very immediate thing. But, um, but also through just parameters that are complex ways of exercising our imagination and… and kind of… but not imagination in a way of pretending, but a kind of a reprograming, like how do we reprogram the way that we look at ourselves while we move or how do we reprogram the way that we move unconsciously or… Yeah, this kind of create… creating artificial organisms or something. What what what obviously comes… I think it’s very like… I think it also is very influenced by a very… in Portugal it would be ‘agridoce’ (both laugh), our sweet and sour relationship with somatics. So I think in a way, I work with very somatic strategies where we try to visualize things and kind of embody them, but in another way, very much questioning all the the authority questions around somatics. Yeah, so I think all my work is about that, it’s about like creating spaces through assemblies of bodies, creating spaces through common investment of energy, being through describing it or through dancing together, or that you actually can transform the space you are in and the body through what you are doing.

performingborders (Xavier): Nice.

Dinis: I don’t know, I think lately I have… I have thought that it’s like… That there is something about like a non esoteric spirituality or something like also in the last years in the work that you have seen. And in other works, I have been working so much about this relationship with nature and like, what does it mean to be a queer person in nature? And at the certain point, I was like, OK, maybe this is about like… Yeah, this could be some kind of spirituality without religion, spirituality without… Without the idea of something else, but with the idea of relating… with an idea of like contemplation and relation with, with the complex transformability or mutation that is already happening in us, inside of us and the things around us. Yeah, to just kind of… To relate and contemplate and interact with this… with this complexity.

performingborders (Xavier): Nice and how how do you think the work has changed since those two times that you’ve got to perform in Portugal contexts? The ‘Cyborg Sunday’ specifically, has the work changed? And how is that… How is that change for you as a maker?

Dinis: Yeah… hhmmm… It’s interesting because the first time that I performed this work in Portugal was within the opening season of Rivoli. Rivoli is this… I mean, you know, it’s this city theater in Portugal that was closed down by the Right-Wing Government that was in Porto. Then when it was changed to a kind of a liberal government, it was reopened and there was this opening season, and I was invited to show it there. And back then, I was kind of in the ending period of creating the work, the work was like basically almost done. And it seemed to me very absurd back then to come to Portugal with like an international… I mean, Porto and Portugal was a place that was quite stagnated in terms of art where unemployment was urging. So it’s just absurd to me to just come in with this kind of international team of performers. I mean, it was not that they were superstars or anything, but still I felt that at that moment there was something that needed to be done. In the end, like that would involve the people that were in this place and so we did an audition and we did the Portuguese version of the work in there. It was from the beginning, a thing that was only going to happen once. And so we showed the work there. And then I only showed it another time in Lisbon at ZDB (Galeria ZDB). So then the work has been touring… even when it was performed in Lisbon, it was with international team and then… Now, I did actually the same, so I, I, I re-staged the work with a local group. It was half because of the same reasons, because I think that Portugal is in a point where it makes sense to engage with the local like to… I didn’t really feel it was the moment to kind of come with an international team of performers and just do my thing. I thought there is I was also very interested in this kind of…the new fluxes that there are in the city, but I think there was something very, very interesting that happened when I left because it’s like my generation kind of left the country at the same time that a lot of immigration was happening from Brazil. So I was also like I thought it would make so much dramaturgical sense to involve all involve people from Brazil and Argentina that are living now in Portugal, all the team, and to kind of understand what is the relationship in between this fluxes and also use it as a way for me to know people that are working in Lisbon at the moment… the difference is that, I mean, there is a very big difference. When I did it in Porto, it was a pre-première. So it was like the work has never been shown, and now it’s like the work is… I don’t know if it’s in the end of life because all of a sudden it’s having a revival and people now want to program this version that was shown in Lisbon. So but, um, yeah, there is this kind of before and after thing. I am in a very different place in my career. I created this… I actually wrote this story when I was living in a caravan in Stockholm because I had like – because I moved to Stockholm with a private loan that was slowly emptying out. The beginning of the second year of my Master’s, I had four thousand euros in my account to finish to do the Masters for a whole year. In Stockholm is not exactly a lot of money. I used to live in a boat where I paid very little money, it was like a ship, an icebreaker. And the guy that owned the ice breaker decided to sell this ice breaker, there we paid like €200 or per per month in this ice breaker. And I mean, the minimum rent for a room in Stockholm was like for four hundred euros.

So then after a very long crisis, I just had to buy this caravan for one thousand euros and I was like, ‘until I can do something else or maybe for this year I will live in the caravan’. And then everything kind of changed very quickly. After one month that I was living in this caravan, I got this co-production with Kullberg and then ‘Black Cats’ really started going and I got a bit of funding from the Arts Council England, but also a co-production from the Cullberg Dance Company here. So things changed, but this text was very written in this tipping point in like in a moment where the future was extremely uncertain. So I think there is something almost like… There is something in this story that is kind of about consubstantiating a space that I needed or something. Sorry, I got a little – yeah, so this to say that I am in a very different point, nowadays. So I mean, for me to re-stage this piece is like… It’s still a piece that tells so, so much to me. But it’s also like… I’m clear we’re re-staging a piece. I think the questions that move me today are others. I mean, that’s something… that’s a question that I had a lot, because when I was migrating – this whole period of making life possible in another place – that was a period that lasted for maybe five years, six or seven years. I mean, that was the main moving forth of my work as well, and that was kind of researched as a theme. Whilst nowadays I have, I mean, that’s not my life anymore, so I, I think nowadays, other questions appeared. I mean, obviously they are not separate because the questions of transness that are part of my work today are part – I mean, they are present in ‘Cyborg Sunday’. In ‘Cyborg Sundays’ everyone has… all the performers have a wig that is a replica of their own hair and at a certain point they exchange them. So, I mean, all the things that are in my work around transness and about questioning… I think my work has a lot of like… Questioning the aesthetics of queer aesthetics and kind of shuffle them and I think at a certain point I was very busy with like ‘what happens when one queer aesthetics become so commerciable, so profitable, and how do we escape its appropriation?’.

I think that has also to do with kind of reinvent our masks or reinvent the way we kind of mutate out of the appropriation that society wants to do of us. So I have always been kind of trying to… Yeah, I think my works work is also like very much in reformulating this, like, I don’t know, I think I’m very busy with, like, what is queerness when it does look queer? What its like… what are trans bodies that are maybe not visibly trans bodies? To kind of also deviate the focus of these things from its visual appearance maybe, and to their recognizability and to kind of produce new formulations, even visual formulations out of its escape, out of escaping that recognizability.

But sorry, I got the bit taken away because you were asking about work and the difference of showing the work. Yeah, I think that is the most… the difference. At the same time… At the same time, works are kind of vortices of reality. I mean, that’s very much how I think them. I mean, because this was such a ritualistic work or so in a way, I mean, by the end of the day, when I’m there and I’m looking at the work and they are performing it (I don’t perform in it) where I feel kind of in the same place. Like, I don’t know, I think works, I think very much of work as… as a temporal reality, like work build realities, so for me, the works are their own time, so it’s not.. it’s not so different, I think the things that are around them are different. And those are maybe like for example, I mean, in the original cast, there is a person with disabilities. And there is… it’s a very interesting work because through this maybe seven years that we have been touring with the work, I mean, there is a person with cerebral palsy in the original cast and during the seven years, someone in the cast has gone through a transition as well. I also went through one (laughs). So there are, there are things in the work that were like a strange premonition, but I also haven’t changed the work. Like I have changed… I have changed things that I wouldn’t dare to say back then. I have formulated things for myself, like there is, for example, at a certain point they are describing a group of four friends that are having sex in the forest. And when the work premiered, this were all cis bodies. And so we have changed that very concretely and also the casts have become… I don’t know if I should say that they became more and more queer because, I mean, there were queer bodies that were just not out there in the beginning, what I also find very interesting. But yeah, I think the piece became more ostensively queer, I would say, and in this restaging of the work four of the five performers are trans people in a way or another, are trans non-binary people. So I think that changed in terms of visibility. I mean, I think that changed in my work in general. Like, I have created through the years more and more precise rules about who I invite for my work and counterbalancing absences in the scene.

performingborders (Xavier): Can I ask perhaps one kind of final question? Which is this idea… we’re talking so much about a temporality in context and how those things kind of change and change us, in our bodies and our own understanding of our practices in a way… I just wondered if you could reflect a little bit about how …language for instance, your own language, be it a vocal language or a physical language, how does it change, if it does at all, depending on what context you are? Because it seems to me that you, you operate so much on a contextual level, both in terms of cultural understandings of the stuff that you’re kind of exploring, but also in terms of the relationship with with the means of production, to use a very Marxist term. You know, like, you know, you’re talking about like, you know, moving away from which allowed you to kind of create this kind of work or you now are kind of able to operate within those things in a way that actually you understood that in Portugal perhaps bringing that work needed some local contextualization of communities, right? Local people and local laborers, I suppose. So I wonder if you can reflect on just a tiny bit on that, on perhaps how context impacts your work and your understanding of your own language.

Dinis: It’s a complicated question, isn’t it?… Because I think, like… I think I’m always in this balance between the things that move me, that are maybe things that I experience and that I experience in my daily life or, I don’t know, there is a source of my work that is experienced in life that is going into the streets. A lot of times when I when my group works finish, people come to me like ‘where did you find these people?’ And I’m like ‘Oh, I don’t know… there’ Yeah, I mean, I think there is… there is a part of my work that is really like on creating criteria on how I live my life, where I choose to be at what time. So in that sense, I think my work is very penetrated by reality. But in another way, I really think the works are kind of universes in itselves. So I like to make the works kind of elevate from a direct comment on a specific reality. So I think the works, on a more abstract way, I would say, are not commenting directly reality, but then I kind of search… ways, I mean, it depends a bit like I have pieces that also like the solo that you just saw (‘Yellow Puzzle Horse’ at CITEMOR Festival) it tours, of course, but sometimes there are just possibilities where it’s more possible to kind of articulate a context. And then I really try to kind of weave this with the context. I really try to articulate contexts behind the works that I kind of feel that they swept into the work. Like when I choose people, like I take ages to choose the people that I will work with because I can’t work with so many people… There is a lot of people that I want to work with, but also because I think it’s a balance in between who I feel that I want to work, who I feel that I should be working with, who is missing in these teams, who is missing in society. I think it’s really a balance for me, and I think that balance is really important because it really, really sweats, passes into the work like…

I mean, the difference in between having a team of white abled people and a diverse team with some criterias, it’s not only that you are doing good for the world, is that the dynamics in this group will be completely different, like it is going to be a different work. Uh. I don’t know, I was having a conversation yesterday where someone was asking like, ‘but if I want to do this work and I want to talk about this thing – (that was a quite normative theme!) – ‘do I have to include these people or how can I put these people but still talk about the normal people?’ And I was like, no, but it’s not… You are not going to do that. Like, the people will change the world. We will be talking about other things. So I think. I think that for one side, the context where I live and the context where the performance lives transforms the work that we are doing, and the questions that I arrive to the works with. In another side, I think that the constellation that I create with the team creates more a second context, that is this context that is kind of the base to create the work. And then there is other fluctuations in relationship to the context that you show. I mean, I remember when I started performing in Brazil, and in South America in general, but in Brazil in particular, because Brazil had such a strong history and it’s such a strong reference in terms of Trans, thinking and I was very like ‘What do I have to say about, like what is the value of my work here, actually?’ And then I kind of understood what it was because because my work, in a way, in so many ways works and draws a connection in between Transness and the means that a body has to perform its Transness. And I think that’s obviously very in a very different way the question in the Brazilian queer context. Yeah. So I don’t know. Sometimes there are also meaning, I think meanings or readings or relations in the works, but you’re not completely aware that they kind of bloom while the work encounters other… other… other perspectives over it.

Dinis Machado (They, Ela, Hen) With a background in dance and visual art, Dinis Machado’s work is informed by how the sculptural construction of objects, spaces and bodies is reclaimed and worked as choreographic material. In a post-somatic perspective, and caring about bodies that do not conceive, perform or imagine themselves as they are medically described, Machado works with ideas of mutation and transformation – psychedelic bodies that they imagine, claim, and consubstantiate for themselves.

Born in Porto, Machado has been based in Stockholm since 2012. They studied MA Choreography DOCH (Stockholm), Independent Studies Program at Maumaus – Visual Arts (Lisbon), BA in Theatre by ESTC (Lisbon) and studied ballet and contemporary dance at Balleteatro (Porto) from 1994-2002. In 2020 Machado was awarded the Birgit Cullberg Stipendium by the Swedish Art Grants Committee / Konstnärsnämnden.

Their works Site Specific For Nowhere and Cyborg Sunday were part of Moderna Museet’s quadrennial Moderna¬utställning¬en (2018). Their work has been presented in Austria, Croatia, Uruguay, France, Sweden, Germany, England, Argentina, Chile, Brazil and Portugal in contexts such as ImpulsTanz, Weld, Dance 4, Chelsea Theatre, FIDCU, NAVE, Festival Arqueologias Del Futuro, ZDB/Negócio, METAL, Chisenhale Dance Space, Colchester Arts Centre, Rivoli, CCB, Festival DDD, Citemor, AGORA, Reflektor M, among others. dinismachado.com

Xavier de Sousa (he/they) is an independent performance maker and culture worker based between Brighton and Lisbon, whose practice explores personal and political heritage within the context of discourse on belonging and migration.

Through theatrical, durational performance and moving image, Xavier explores the dichotomies between the live experience and agency in the performance space, as well as written text and queer methodologies of performance and research.

Alongside his performance work, Xavier has written for publications such as In Other Words (2020), Les Cahiers Luxembourgeous and Centre National de Littérature Luxembourg (2021). He curates the digital platform and commissioning programme performingborders and New Queers on the Block, Marlborough Productions’ Artistic and Community Development Programme. He is co-founder of Producer Gathering and activist group Migrants in Culture. He is a member of BECTU and ITC.

This commission is a part of the performingborders 2021 programme, supported by Arts Council England. The full August newsletter: Shifting Landscapes can be seen here.

Featured image credits: Performance of ‘Yellow Puzzle Horse’, Dinis Machado, courtesy of the artist