Pensamiento semilla/ Seed thinking | Interview with Germinal (English)

14th August 2023This text is part of Anahí Saravia Herrera’s commission Embodying Resistance/Encuerpando Resistencia: unfinished reflections from the Bolivian territory – see the full commission with further interviews and texts here.

“I am Germinal, a research semillero, a constant opening, at the beginning more than a dozen bodies composed me, right now two curanderas1 think with me. We think rooted in compost and try to use time in circular strategies of thinking, I live seasonally. I saw the light in the middle of a post-pandemic process. I was born in a garden in Sucre, Bolivia. In a kitchen in El Alto, La Paz; in various other kitchens and flowerpots and flats in buildings in eastern Bolivia; throughout a territory that we do not necessarily all find ourselves treading: that is why we virtually work the soil of our relations. I am a daughter of virtuality, I was born through provoked affection: I bring to us a seed thinking: kepicheo2 as a gesture to decolonise knowledge and La cura[nde][du]ría3 as a device of care: an unfolding of and for a contemporary curatorship, a necessary transformation of the relations established with respect to the work of the others, within the world of art”.

Germinal (here making reference to the word germinar, to germinate) is a project that was born from a desire to gather and create space for dialogue with those with an interest in that which we call ‘live art’ being something that goes beyond an artistic product, but rather a process of sharing, dialogue, connection and a space where the sensuous and the creative can meet life. It is a space for stewing and thinking collectively with those within and outside conventional art spaces, with a particular sensibility towards art and a desire to seek out knowledge from spaces of agriculture or land tending and what they can offer to a process of collective growth. The first iteration of the project Germinal: Semillero de investigación para las artes vivas (Germinal: Seedbed for the research in live art) was started in 2021 by Paulina Oña and Tika Michel, initially hosted at the Centro Cultural de España in La Paz virtually during the pandemic. Since then, Germinal has hosted more gatherings in person and online. Their second largescale gathering was in 2022, Tejeduria Germinal: Mesas de trabajo para pensar las artes vivas desde el territorio boliviano (Germinal Weaving: Working group to think through live art from the Bolivian territory).

They use the structure of a semillero to gather and structure their research, stemming from the word ‘semilla’ or seed. Semillero is a term used to describe a research space to seed ideas, typically in academic contexts but also outside of them. There isn’t quite an equivalent term in English that I know of, but terms like ‘seed bed’ capture the literal meaning of the word and the intention behind the project.

Paulina and Tika met through the Maestrá Interdiciplinaria en Teatro y Artes Vivas/ Interdisciplinary Masters in Theatre and Live Art at the National University of Colombia. Both had migrated there to study from Bolivia and after finishing their masters, were looking for a space to seek out performative interdisciplinary practices, with the intention to subvert academic spaces for research and open this up to a wider audience. In doing this they were led to question and consider everything that could be live art, especially in a context like Bolivia with cultural practices that may not label themselves as such. What has resulted is a project with an emphasis on the research process over the outcome which looks toward live art practice as lifelong, and at creative practices not categorically but as open-ended and entangled with the everyday.

Note on translation and the final research:

As someone with access to both Spanish and English, this research has happened across both as well as through local dialects. The final works are edited versions of our conversations, which took place in Spanish with interjections in slang, Aimara and Quechua. The original version of this final text is in Spanglish, with my reflections in English. I have also provided a full English translation. The texts in Spanish were edited with the support of Camilla de la Parra, who also consulted on the translation.

See the Spanglish version of the text, with an untranslated conversation, HERE.

Anahí: Where did the idea of Germinal come from, and how did you come up with the ‘semillero’ approach as part of your practice?

Paulina: After a period of confinement and the end of our academic period, the need arose for us to find interlocutors and collaborators. We had already begun to have these kinds of exchanges here in Colombia, but in some way, it was important for us to create or seek these same spaces of knowledge sharing that we had encountered through our Master’s degree. It is a space of a lot of estrangement, and so much commotion. It is also a space for a lot of experimentation. The desire to find such a challenging place for thought, and not only from artistic practices but also from all kinds of vital pulsations that are carried out to be able to find these languages and words, these devices that ‘live art’ proposes. This all put us in a place where wanted to do this.

We referred to the figure of the semillero which, despite being a very academic proposal, it was something we had brushed against in an academic space run by a professor, so has a hierarchy, in a way. It seemed to us like an interesting structure, if we managed to turn it around, if we managed to propose a horizontal space for the research group, if we managed to remove the hierarchies that existed and preserve the spirit of research and investigation that the research group has. And to also create a space for meeting with many other people who may not have the same line of research as you. So, without losing that desire to search, research, and play, we took on the name semillero.

A moment had come when we imagined the seed as a creative power, as a minimal power that brings with it many possibilities that perhaps are not in our hands. After that, we became aware, not only of the seed as a unit, as a power, but also of everything it implies: the terrain where it is found, the conditions, the contradictions it implies, and all these vital processes, the life or death they go through, and everything that could happen around it. We joined together in the voice that the time has come for the weavers. It’s time to throw seed, wherever it is, to see what happens.

During these first two years, we have had the support and funding of the Centro Cultural de España in La Paz (Bolivia), who were very interested in having a programme of ‘live arts’. Because we can’t deny it, until now and for the last two years, it’s a term that is being used a lot, reflected on, even categorized, to name certain practices that perhaps don’t find a place to sustain themselves given their more subversive and outsider qualities. In terms of the practices they propose, which are not just performances, not just theatre, not just dance, but are crossed by the vital powers of the bodies and the corporeal entities that are present in these manifestations. So, in that sense, it resonated with them that we could carry out this process, taking into account that we had been immersed in some spaces with certain people, including collectives that are very, very strong and very powerful at the moment.

Anahí: Your first meeting in 2021 was led by your search for a space for all these reflections. To begin the project, you opened a call for proposals and invited different people. How did the process of creating a body for the project go?

Tika: We had been mumbling about the idea of wanting to collaborate with people here in Bolivia. Above all, we also wanted to invite and interact with the people and teachers we had met in Colombia, and other people from other places.

When we presented the project, we talked to several of our former professors and other people with interesting thoughts and research, and we launched a call for proposals. We did the five-month project. It was super long, and we divided it into four ‘seasons’. The point was that each season had certain topics, and initial ideas with guests related to them.

So, the call was opened and people came in. One of the things we liked the most is that there were people, although few, who stayed from the first season until the last, and they are people with whom we are still collaborating. When we started, we said: “At some point in the future, we can put a group together and we’ll see what happens”, but still in our heads the body of this semillero had not yet fully manifested.

Time went by and people came and went, and the ‘air’ and the space that they generated through this movement, was what strengthened us more, and more. In other words, new people came in, new people left, there were people who stayed for two days, other people who stayed for only one season, others for two seasons, and then the permanent ones. At the end of that first project, we realised that this was the body of the semillero. We were going to be there, each of us with our own projects, another group that is a little closer, but still with their own projects around them and other groups that appear, go out, come back in and are there influencing the space. This has opened up many ethical questions about authorship, which always generates a problem, especially when you have to apply for funding and things like that. But luckily, we’ve been able to have moments of reflection on this. From there, of course, there have been other kinds of ramifications, of instances and other territories involved too. But this is the body that the semillero took in the beginning.

Paulina: I think we’ve learned a lot from this experience with the semillero, because for us Germinal has a life of its own, it does its own thing, it brings together the people it has to bring together. And we realised that, effectively, this was open for whoever can, whoever wants to, whoever has the time. Whoever has the desire to be there will be there, and without the pressure of having to consolidate something. I think that’s what has given it the possibility of continuing to exist, of continuing in the times in which it has been proposed.

Another thing that is also important to emphasise is that this whole first stage was virtual. We were in a moment of confinement, at a time when the pandemic was still going strong in different territories. I had already returned here to Bogotá, Tika was still in Bolivia. So that’s what it was too, wasn’t it? How are we going to resolve and define this ‘body’ without a body? Effectively, by assuming ourselves to be daughters of virtuality, we had to understand that this space and this relationship had been created from this place. This space has also wanted to be face-to-face, and later on, we managed to meet each other, we found a way to find each other. I think this has been one of the coolest things that has happened with the semillero, that it hasn’t stayed in the (virtual) space, but that it mutates and goes where it wants to be, where it wants to germinate. […]

If we had remained in the mindset of: “I really have to be in Bolivia to do this”, it would have been something else, but I think that we have given openness to this quality of presence that we have proposed, which has meant that the dialogues have entered through other spaces and that the sharing has been in a different way. Surely all of this led to the fact that the meeting and the physicality eventually became too important, and this led to a meeting finally taking place in Cochabamba4 in 2022.

Anahí: It’s important that you have created this space within the Bolivian context, where in general there is no career or formal space where one can experiment with practices outside the fine arts, multidisciplinary art, for example, or performance. I don’t know if you see it the same way, or if you have seen that the artists who have come to your project were artists who somehow couldn’t find a home in other spaces.

Tika: I think at the beginning we never restricted ourselves to calling out to only artists, and even more so in the Bolivian context, because it’s a very subjective category. Obviously, for many people, it’s a profession, but there is a whole range of practices in which quite conventional work and artistic professions oscillate, and in there somewhere begins to emerge a mixture that is quite characteristic of Latin America. We didn’t know how to convene people so as not to restrict ourselves to people who are interested in the arts. Evidently, in the end, the people who have stayed are people who work in many other areas, but who also have practices that are sensitive to the artistic. […]

The fact that there are no spaces in Bolivia to develop this work really sucks, but at the same time, it’s an opportunity, because the people you meet come from themselves, from a very authentic exploration. Not from a “I learned this and I do it in a certain way”, but from intuitions and searches that come very much from their core, very much from desire. When the possibility to gather appears, this all bubbles up. It is not something that is closely linked to an academic rhythm or to a rhythm of research in the conventional sense.

Throughout the first iteration of the project, Germinal worked closely with the Semillero de Artes Vivas in Pachuco, Mexico who acted as witnesses to their process, a kind of critical friend to be present throughout as a way to feedback to the project. When the project started, their first suggestion was that, essentially, they bring their hands to the soil, and together, quite physically, get involved in germinating and seeding together. This brought further reflections on what it means to host and grow knowledge together, not just on artist practices but on how these intersect with life around us.

Paulina: […] I feel that for this reason, thinking about the seed from its potential for performativity, from these [other] spaces, encourages other reflections, doesn’t it? To say: “OK, what do I have to put in it? What do I have to do? What is this compost thing I hear about all the time?” You really have to enter into the frustration of not being able to sow anything, or of everything dying. I think that this gave way to being able to see other places from where you could look at what it is we were doing, what is this thing I call art, what I call handicraft, what I call my practice, my craft.

We want to insist in looking at the artist as he is looked at from other cosmovisions: the farmer artist, the poet artist, the artist who looks at the stars, as one might see from an Andean cosmovision. It is not necessarily from virtuosity that something is born, but from what pulsates in the body so that something can be made. Many of the people who stayed have a knowledge of the earth that is fundamental for us. It is vital to have a talk with these people. They are the people who are much closer to other types of processes and, therefore, they are also in other types of community relations with their environment, with their activist practices. […]

Everybody, when they applied, asked: “Can I bring my project? And sure, obviously you can bring it, but we’re not going to work on your project. In the sense of an art workshop, we’re not going to do that clean curatorship so that it’s perfect, but rather to put you in such a conflict with the work, that you question it, and so that an art project becomes a life project. That the project becomes something else that you can talk about with other people who aren’t necessarily artists and who perhaps will contribute much more from ancestral knowledge, a knowledge of the hands, a knowledge of other types of approaches to what, for us, encompasses this whole space of sensitive practice, more than artistic, right? Working on sensitivity is what has been driving us to continue with the project.

Thinking about the role of the body, a big part of Paulina and Tika’s work, is through sensitivity, sense and the sensuous, and where that sits in knowledge-making. Reading through their texts, it’s impossible not to imagine the gestures that run across them, from disentangling yarn to burrowing your hand in the dirt. Their research brought them to collaborate with researcher and thinker Marie Bardet, who is thinking through gesture, bringing them to think beyond the body as an essential and individual entity and towards the body as something that is interlinked, in an ecology that is made up of common gestures and relationships to others. Bardet has written a text entitled Hacer mundos con gestos (Making a world with gestures) – which is an interesting reference for this. Thinking about where the body sits in their project space, they said:

Paulina: I feel that the body appears when the others appear. And this is something that is completely present in all sowing practices, in all these spaces for thinking about plants, the rhizomatic. All this that is now very present with the mycelium stuff, there is a place where the body manifests itself through the others, through alterity. There is no need to remain in these words, “alterity” and “gesture”, no need to remain only in the concept, or in how we have been given these words or these definitions, but to think further about how to make a gesture with the body. […] Following this, putting our bodies in front of a camera, trying to share some gestures together, cleaning, washing, sowing, harvesting, chasing wild grasses through the streets with our phones. All these little provocations, in a way, have been moving from the body as a word with a concept, from a very heady thing, to a place where everyone from their own practice can begin to embody these investigations.

Anahí: I am very interested in your experience with the use of the terms “live art” and “performance”. Within the context of the project, you refer to a difference between each of these practices, could you tell me more about this?

Tika: I think that at certain points, they are practices that touch each other, that can share many things. We have always entered into that conflict and dialogue on what they are […] In the last gathering, we had as a collective, there were some spaces to try to define those terms. One of the things that became clear is that “Live Art” is an instance, a moment that is going to happen. Just as cubism has already passed. What is not necessarily going to pass are the ways in which certain transformations and changes that are part of life itself manifest themselves and happen.

The moment institutions begin to take these terms, suddenly they finance them, and that is what is happening here. From being an intuition, from finding a space (because I don’t find my space and this is the one that more or less gives my work a body), suddenly it becomes institutionalised, and little by little loses its strength. In a way, our work is linked to this because we have obviously studied something with [the term ‘live art’] in its title. We understand that it’s a title and that what is underneath are those forms of manifestations, those practices that will continue to come together and that we will continue to explore, and these are the [forms] that we would call our art, our way of traversing these artistic, academic, social spaces… I think I’ve made everything more complex, but it’s the truth!

Paulina: The term ‘artes vivas’ also arrives in Colombia, obviously taking live art from the West. In any case, I feel that what live art does here is like a kind of cannibalism. Something anthropophagous happens with that term. To say “live art” in Europe and “artes vivas” here in Colombia are completely different things because here it’s very contaminated by its context, by the 50 years of war they have, [by] the political processes, by these other spaces where art is made, which are completely different to what happens in Bolivia, despite the fact that they have South America in common. So this term is very much in use here, very traversed by many things. […]

When we said last year: “Okay, we want to set up a working group [in Spanish the term used is mesa de trabajo, literally translating to ‘working table’] to study the idea of live arts in Bolivia”, […] many of the people who came were very curious. […] However, we didn’t end up concluding what it was. […] Later, when we were able to work with some fantastic accomplices who were Sofía Mejía [from Colombia] and Marie Bardet [based in Buenos Aires], both from the academic space, we said: “Chicas, let’s see, what is this?” And they, without knowing much about the Bolivian context, proposed a series of ways of looking into this and proposed that perhaps live art has been happening in Bolivia since long before there was a career in it here, but that they weren’t named in this way. Perhaps, rather than concentrating on the term, we should concentrate on the practices, which could be immersed within our community of co-conspirators. […]

That desire, I think, was what stayed with us the most after these mesa de trabajo. In the end, it was like: Which table? Nothing! Let’s make a bonfire, let’s put some water on, and chat. And in the end, that’s what it ended up being. Many times, Germinal and all these processes showed us that, effectively, the only thing that can be proposed or that can be provoked is a space of encounter. The living arts, effectively, create a community, a community to olisquear [smell things out], is something we would say…[…].

And I think that for us, more than performance as a category, I think what interests is performativity: of everything, from gesture to the possibilities of doing (always in the gerund so that something more than a closed verb can emerge). Above all, to think about what our kinship is: how does it relate to dance? to theatre? Where do these complicities come from? Who are our accomplices? Who are we citing? Who are we talking to? […] For us, witchcraft is very implicit as a technology in all of these spaces, in the face of science, in the face of what is already known, which is closed, in the face of all this knowledge that is more categorical. […]

Returning to the topic of working transnationally and how the project has opened doors to include diasporic voices in the conversation, we spoke about what it means to speak from and to a locality, from the diaspora and how this can sit separately from nationalistic longing or connections across constructed national identities.

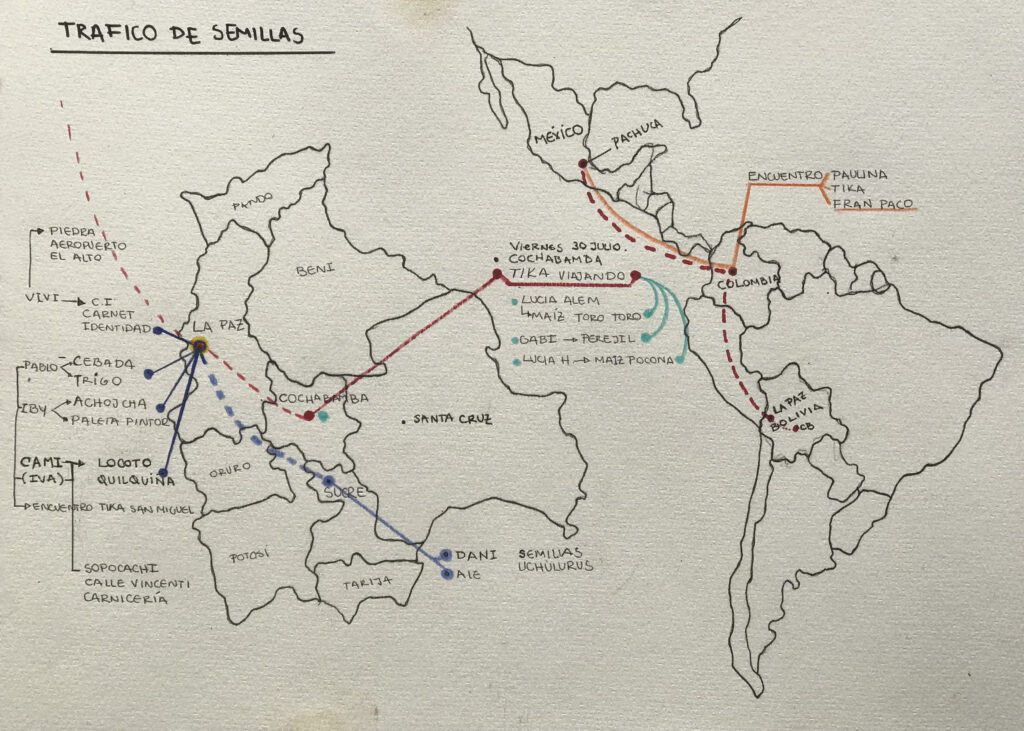

Paulina: We think about diaspora, not as this nationalist diaspora that has to eat its salteñas on the 6th of August, […] but rather through the questions: How does one carry a territory within oneself? How do I bring the mountains with me? How do I think from other territorial and political spaces? That which we call Bolivia, with all its contradictions, without entering into chauvinism, without entering into nationalism. I think that in this sense, it has been very important for us to continue with this dialogue as we enter this space, because we consider that it is also a type of trafficking. Trafficking is something that we have been strongly nurturing and are trying to understand, taking away the moral charge that the word “trafficking” has in terms of borders and the migratory options that exist.

So, this conversation is proposed above all because of this interest in the fact that Bolivia is not only there in square kilometres, but that in fact each person carries it with them in their own way. For example, a friend of mine, Sharon Mercado, who lives in Berlin, works with cumbia and technocumbia, she works from this place of party, beer, and excess. It could be Bolivia or it could be Zimbabwe, you know what I mean? It has particular characteristics that mean that where she is speaking from, is the space that she considers to be her way of being and thinking in, for, and with Bolivia. That was something that interested us above all, to open up the dialogue and not just think about it on a GPS level, but as situated from a place. And to open up the possibility of thinking in a situated way. Thinking of the compass as a space, more than as a map or a geolocator, and thinking of this space from an ethical perspective that makes you question and not only glorify your customs, your forms, your context, and enter all these contradictions. We considered that the good thing about making it a cross-border exchange had to do with this potential to move back and forth.

Tika: […] Until now, within Germinal, the encounters we’ve had have been like this. The latest version was specifically for Bolivian people, so that this thinking on ‘live art’ and everything that is art, could begin to be handled and disrupted by people who share a common, but also different, imaginary. So that these concepts begin to have their own [contextual] meaning. Personally, it’s one of the anxieties I always have. We have had the privilege of being able to go out and study abroad. What do we study? Concepts and things brought from Europe. We are part of this colonialist mechanism of thought, aren’t we? How do we take responsibility so that these thoughts, which in some way are part of this colonial chain, can be subverted a little? How do we take responsibility for these privileges of knowledge so that we are not the ones who come to “teach”? Because we don’t want that. I think there is a responsibility there to turn that around so that a lot of knowledge and things that are very interesting can be re-thought, re-written, re-interpreted, and made sense of in that territory with people who have a common imaginary and sense of having inhabited that space.

Anahí: My last question is, after your second meeting and having seen and worked on the live art ecology in Bolivia, what has come out of the project?

Paulina: One of the most important things, is that we’ve taken away so much importance from the term “live art” and we’ve realised that by digging into everyone’s practices, we’ve been able to find all the potencies that could be present within the field of live art, without the need to call them by that name. Perhaps Bolivia doesn’t need to name things, Bolivia just does them. […] I feel that there are times when we go through this whole process to only to realise that in the end, it’s not that important to name the things that happen in a country like Bolivia with such strong internal contradictions. That would be one of the things that has come out of the project.

Tika: On the other hand, we also realised that by doing this, by opening up and breaking this category and this definition [of live art], what happens is that you realise that there are a lot of people doing things and making work, who don’t name their work from the place of [live art], and that you haven’t seen their work from there either. There is always this idea that there are only a few of us artists in Bolivia, that we all know each other, and that is a totally false statement. You have to go to other spaces, you have to do other things, you have to move away from your comfort zone and safe space, where you’re used to doing your practice. People are doing this work every day. […]

Paulina: We think that live art in Bolivia stimulates life in the practices we hold. They take very different forms, some people come from agriculture, some others from writing, and some from activism, they all start from different spaces that don’t have to do with a virtuous technique of what they do, but rather with the query: How do I use this to question myself? How do I ensure that I become frustrated every time I’m about to finish doing something? […] That specific way of stimulating thinking has to do with live art in that particular territory and I think that’s something really great. Rather than ending up with a catalogue, with an encyclopedia about live art in Bolivia, which happens a lot, right? From Ibero-America, they’re able to say what live art is in Latin America is by grabbing a handful of people and putting them in a book…. and then what? That’s one way of, as you say, “mapping” live arts. But you also have to question that map. You have to present yourself from situated thought, a space that is not geolocalised. Open the map, expand it to an atlas, expand it to another place, and turn off the GPS. So, in that sense, I think it even comforts us because it puts us in a place where we can ask, Is that what all this thinking is for? We have found that, indeed, the answer was much simpler than what we had expected. In terms of that particular desire we had last year to think about the term “live art”, ultimately it’s also important not to take the term for granted […] it’s something that is in the process of being thought, and I think that’s one of Bolivia’s great potentials – everything that’s still in the process of being defined.

As I close this interview, I am holding on to everything that is still to be opened, explored, and determined through the lens of live art not as a category for practice, but as a process through which to question, and an invitation to dissolve the boundaries of ‘art’ and ‘life’.

More information on Germinal can be found on their instagram: @germinalsemillerobolivia, and through a blog page on the Centro Cultural de España website here (as of August 2023 this was not available but should become available soon).

Tika Michel: I’m tika, I’m a graphic designer and interdisciplinary artist, my practices oscillate between walking, fiction and encounters. I’ve been working as an actress since 2004 and since 2013 I’ve been researching expanded artistic languages and performance. In 2018 I studied the Interdisciplinary Masters in Theatre and Live Arts at the National University of Colombia and as a sequel to this experience, in 2021 Germinal was born, a research space for the living: an undisciplined, horizontal, and collective space that continues to expand. I have worked with collectives in residencies and collaborations in several Latin American countries. I currently live in Cochabamba-Bolivia, carrying out collaborative projects and artistic research.

Paulina Oña: My name is Paola Oña, I am the fifth of seven children, I was born in Bolivia after my parents and my older brothers and sisters migrated from Buenos Aires-Argentina, at the beginning of the dictatorship processes in South America and with them, inflation. I have a profession that I never got to practice (I’m a lawyer), but that made it possible for me to study the Interdisciplinary Master’s Degree in Theatre and Live Arts at the University of Colombia in 2017: I decided to migrate because I wanted to study. I am Paulina Oña, an interdisciplinary artist. My artistic practice is made up of a series of gestures that make up not only my sensitive sides, but also the spheres of resistance that constitute me as a migrant, a sudaca, the daughter of a plumber and a seamstress, a witch in a non-binary becoming (naming myself a woman makes me more and more conflicted). My artistic practice oscillates between the fiction of words and the generation of images and sensations, between the real and the virtual, and between theatricalities and performativities.

Footnotes:

1 Curandera literally means healer but in the context of this work is an interpretation of the word curadora which literally can also be read as healer but is also the word for ‘curator’.

2 Cuento Kepi, in Aimara is a way of talking about people who spreads gossip, rumour and stories as a way of disruption. Kepicheo, is a word invented from ‘Kepi’, making it read as a verb.

3 Mix of words, curaduria (curatorship) and curanderia (healership).

4 Cochabamba is a city in Bolivia.

5 6th of August is Bolivia’s day of independence, a salteña is a traditional patty made across the country.

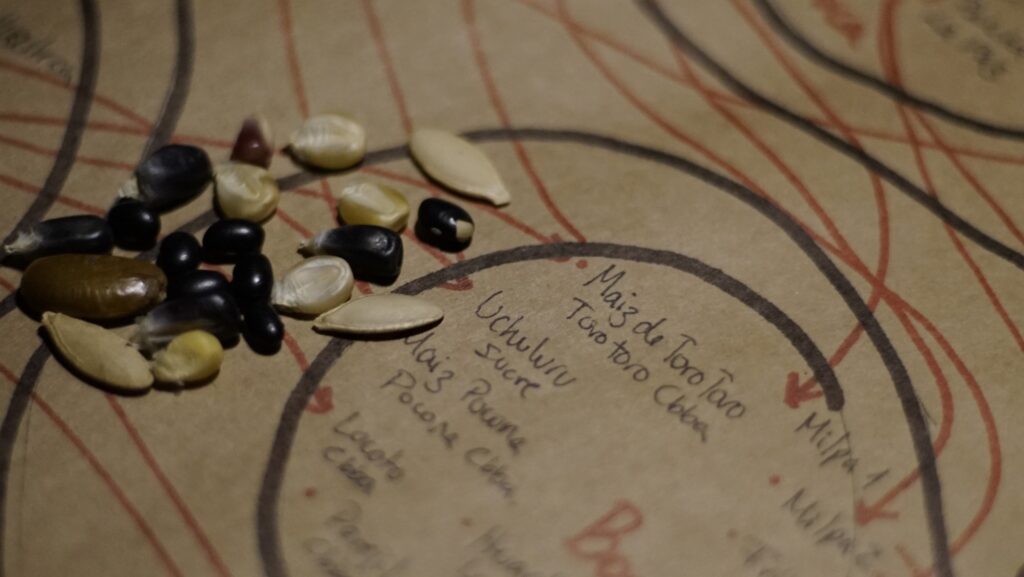

Lead Image: tráfico de semillas/ seed trafficking, Germinal