The street as an artistic/political space | Interview with Alejandra Del Carpio + Calle: Bienal del Performance (English)

14th August 2023This text is part of Anahí Saravia Herrera’s commission Embodying Resistance/Encuerpando Resistencia: unfinished reflections from the Bolivian territory – see the full commission with further interviews and texts here.

When we first began to talk, Alejandra Del Carpio (Ale) told me that Bolivia was the abandoned country for the performing arts in Latin America – a sentiment that I would hear echoed when I spoke to Paulina and Tika from Germinal. Far from meaning that there is no performance or live art in the country, it points to the fact that there are no institutions that support even the more traditional disciplines like dance, theatre, or even cinema. In Bolivia, there are no university degrees in any of these areas (in either public or private settings) and so for many, to be an artist means to leave the country to obtain a degree elsewhere, seriously limiting who gets access to this information and is allowed to call themselves a performer, deepening already wide economic gaps within the arts ecology. For more interdisciplinary, political, and experimental performance work, there is almost no space, visibility, or support, with all platforms and projects being wholly self-organised, self-funded, and artist-run. Building on a desire to create space for this work, in 2015 Ale began a project to create space for these practices and build an invitation not just for performers to come show their work, but for artists from across disciplines to play with what it means to work with performativity in their practice. From this initial festival came Calle: Bienal del performance (Calle: Performance Biennial) which has had three iterations that have taken place in Bolivia, Brazil, and online.

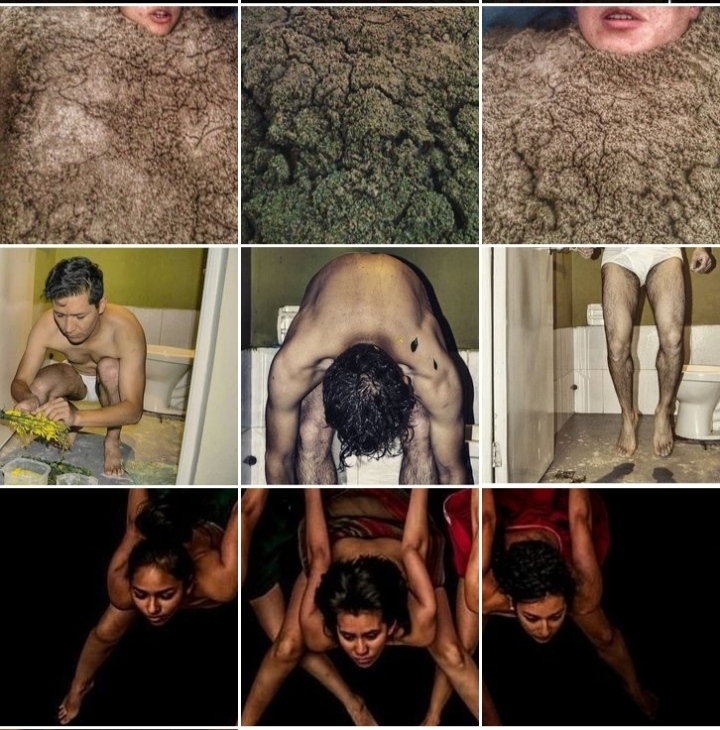

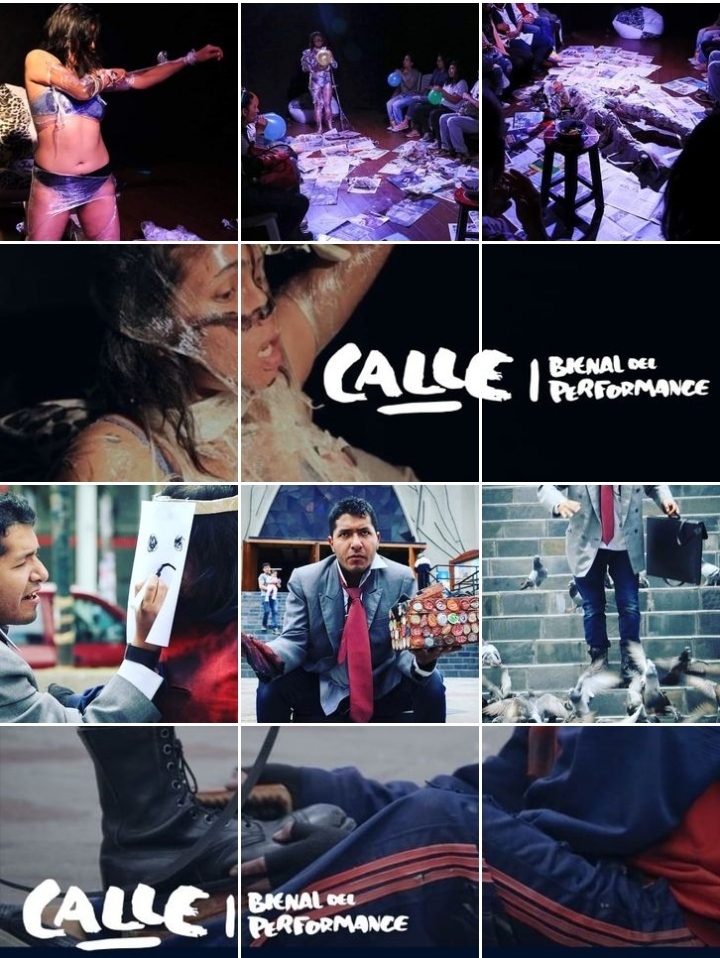

In her own words: Calle is a gathering that happens every two years, bringing together where artists from different origins and contexts work on a theme and seek to transmit their reflections through the symbolic, aesthetic, affective, historical, and political languages involved in performance. Its main objective is the occupation of public space through an artistic intervention that reaches the gaze of people who, for different reasons, are kept on the margins of hegemonic and institutionalised art galleries. Calle understands performance, not as art to be displayed behind glass, but as a living movement. It pursues the desire to put bodies in play with the city, intervening in its everyday life, questioning it, and inviting joint spectator-artist transformation. This event is carried out in a self-managed, independent, and collaborative way, without public or private financial support, and to date, it has taken place in four versions: Cuerpos (2015), Calle.exe (2017), Identidad (2019), and Territorio – Memoria ancestral (2021). Since its first version, Calle has taken place in La Paz – Bolivia, although in its last version, it also took place in Sao Paulo – Brazil, as well as having had video performance screenings in Argentina and Mexico.

In countries where so much of life happens outside and where the public space already holds performativity, building a project based on these interactions as opportunities for artistic and political encounter are particularly powerful. Through this conversation comes an interesting reflection on what it means to take public space as an artist, an action that is political and breaks the format of complicity and immunity that is granted to art in a theatre or a gallery. Suddenly, by taking the work to the streets, the frame of ‘consumption’ is taken away, indicating who the audience is and how they relate to the artist, opening doors for a new kind of relationship between the public and the performer. Working in an incredibly politicised context, the commitment to using public space and placing art on the streets, even in the face of ongoing civil unrest in Bolivia, is something that has shaped the project’s politics, placing it somewhere between art and activism. Rather than look to build an institution or create a space that reinforces a tradition of exclusion, Calle has stayed resolute in creating space for art in public where it might seduce, relate, and speak to an audience much larger than those who might be reached typically. An audience who – when you’re making work about feminism, gender-based violence, migration, and racism for instance – may connect to the work in deeper, more meaningful ways.

We met to talk about this work, the iterations of Calle Festival, and Ale’s personal practice weaving programming, street performance, and curation into her own work as a performer.

Note on translation and the final research:

As someone with access to both Spanish and English, this research has happened across both as well as through local dialects. The final works are edited versions of our conversations, which took place in Spanish with interjections in slang, Aimara and Quechua. The original version of this final text is in Spanglish, with my reflections in English. I have also provided a full English translation. The texts in Spanish were edited with the support of Camilla de la Parra, who also consulted on the translation.

See the Spanglish version of the text, with an untranslated conversation, HERE.

Trigger warning: Violence and sexual assault, not graphic.

Talking about the beginnings of the project and how she was led to create Calle, Ale said:

Ale: In 2015, I was already in the theatre world and I was missing the process of doing research. So I asked myself: “Where are the other artists?” I only know a lot of thespians, but I would like to have more contact with dancers, I would like to know what the painters are doing. And then, in this research, I started to think about performance without realising it.

So I did the first Calle. I did it more to fulfill a desire to research because at the time the project was [still] in its infancy. I started to contact people, to see who was doing performances in Bolivia. What specifically do they do? Where do they come from? What have they studied? […] I was encouraged to do a festival and I wanted to invite people, but I was super young and I ran into many people who were already doing performance who said “But who are you? Why would you do a performance festival?”

I was generationally disconnected from all these artists who already had their trajectory in performance. So, I was obviously an unknown to them. They looked at me thinking: “What are you playing at?” And I decided to believe in my game. I had no budget, I had nothing. I invited lots of artists and was faced with a lot of “no’s” or question “How much are you going to pay me?” or “No way am I doing something with no budget, I’m a big name artist”. […] So it was a bit sad, but at the same time motivating, because I said: “I’m going to do it anyway”.

[…] For the first iteration, I started talking to friends. For instance approaching people like: “You’re a painter, but do you want to do a performance? Are you up for it?” So it was like an attempt to convince people about performance and I started to gather people together this way, some of the well-known artists ended up doing a workshop. For me it was a satisfaction to have brought together for the first time, at least in the history of what I knew, dancers, visual artists, and stage artists, all doing performance. That’s how it was born!

The biennial was born out of both desire and curiosity. When I started researching performance, I was fascinated by the universe of performance practices and the forms it could take, Bolivia already had a long history. Performance practices in Latin America and other territories are also fascinating. The consequent question was how could an ordinary person, immersed in the infinite rush of the city and its noise, be immersed, challenged by, and feel questioned by this form of making art. As a result of this question, five desires were born in me, as an impulse: The first was to take to the street as a public space par excellence. The second was to bring together artists as diverse as the performance itself, as diverse as the society they seek to question. The third was not to ask permission, nor to depend on any institutional hierarchy. The fourth was to build community and networks of artistic articulation. And finally, to raise social, political, and cultural issues in the place where it is performed.

The final result of this first meeting was called Cuerpos (Bodies) and I decided to make the theme poner el cuerpo (translating to putting the body, but implying the process of putting your body on the line, and using it in first person) because whatever path you have had in art, it was an invitation for you to come and put your body on the line. A multidisciplinary invitation, through performance. […] I had nothing and ended up investing all my savings […]. It had very nice reverberations, from new people I didn’t know, people who came for the first time. Obviously it’s also had a lot of critiques. Again, people asked me: “Who is she and what has she done? What does she think shes inventing? She’s not inventing performance in Bolivia”.

Anahí: In London, it also happens that people control performance spaces a lot and at least I, as a researcher and someone who is curious, have entered the field in an interdisciplinary way. I feel that there really are generational hierarchies in the sector.

Ale: There is a kind of hegemony of practice, which I mention in Calle’s story. What defines the space as hegemonic is Who does it? Why? How is it done? How is it performed? Who get to write the book on it? I relied a lot on negative criticism and it made me radicalise my practice. I mean, I accept it, I take ownership of the fact that I’m not from that generation, I didn’t invent performance in Bolivia. But ultimately, what is performance, how many times do we come across performative practices in different disciplines assuming that’s not what they are, who is it that says who is a performer and who isn’t?

The next year I didn’t do it and a very dear friend came to me and said: “Do it again. Nobody else but you is going to do it”. […] I said, “No, it’s been terrible, although it’s had some very positive things come out of it, I have no resources again. How can I do it? I can’t do it, or can I?” And so then, again I said let’s see, I’m going to get friends together, the ones who have given me some positive criticism and see how they respond to the idea. And once again, a new festival is reborn through self-organizing, the second one was called’ Calle.Exe. From there, the biennial was created as such.

Anahí: So you didn’t call the first one a biennial?

Ale: No, the first one was a meeting of performing artists. I hadn’t planned to do it again, not two years later and certainly not every two years. […] In the second interaction, different artists came together, including some who had been doing performance for a long time. It was still small and obviously one develops oneself in practice, right? So the first festival it was a continuous day. The second time, I thought I wanted it to last longer, so I did it for a week, with a performance every day.

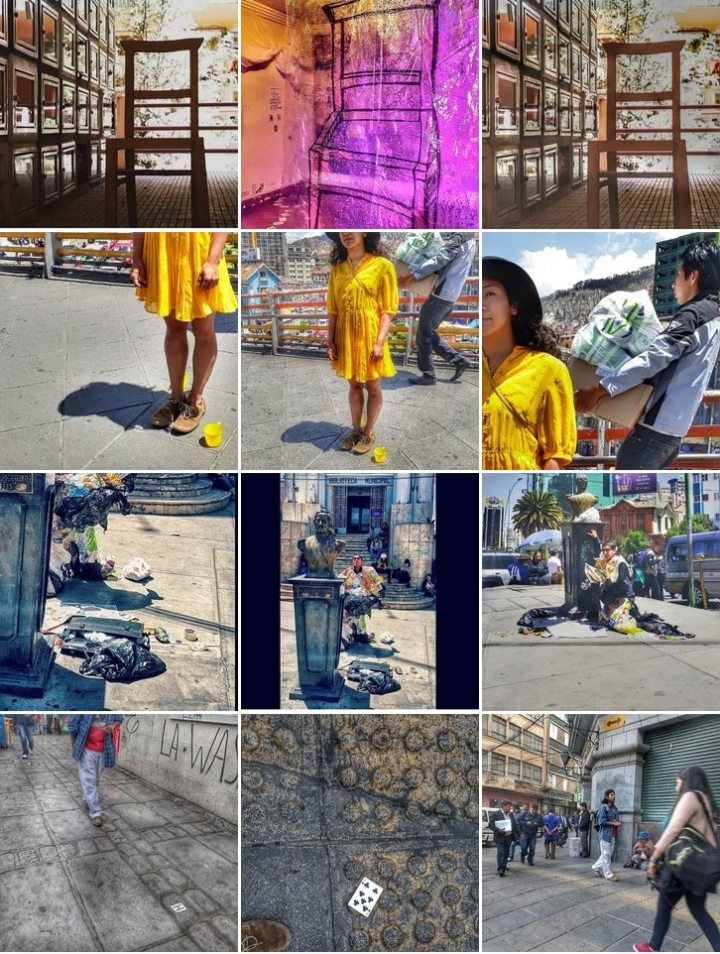

By that point, I had already reflected on what I was trying to do with the festival… Between the two festivals, I had continued to be a theatre artist, I’d done many plays, I worked in a theatre group. The situation was always that there was no audience and whenever I went to see performances, plays, or live art in galleries, it was always the same people. It’s like a complicity. When you go to the theatre, you’re ready for whatever they present you with, you’re going to see it to the end and when it’s over, you’re going to applaud and then you’re going to think about it. When you go to a gallery, you go predisposed. You’re going to accept whatever they’re giving you because you’re prepared for it. Performance doesn’t need people’s predisposition. I don’t want my friends to come and watch and applaud. I want to know what happens to people if we take it out on the street… Are you up for it? I asked the artists. “Yes”, they said, so we went to the street. And that’s when it started to be called as such: Bienal Calle. There were different places it took happened in: Perez Velasco, San Francisco Church, El Prado, the General Cemetery, these were the main places performances were held.

Anahí: This proposition of being on the street, was it new at the time? Street performance was already happening, I imagine, but as a festival, a biennial that took place on the street, was it the first one? Had something like this happened yet?

Ale: I don’t think so. Performance normally belongs to the street, it works in the street, it belongs to the street, right? In biennials, there will always be public actions. […] My questioning wasn’t so much with space, gallery or stage, but with the eyes of those who see it. If someone is going to talk about a political issue, such as violence against women or whatever, that it shouldn’t be for four people who already know about it. I wanted it to be for a woman in the street, who will be called to the work in a different way, to the caserita who is passing by1. Everyone said to me: “But no one will understand”. And I said that I didn’t want them to understand it, I want them to see it and to for the rest of the day keep thinking about what they’ve seen. If someone really wants to understand, they’ll come up and ask. If they don’t, and if they misunderstand it, that’s fine too.

The second edition, Calle.Exe, took place over one week in November 2017. As the next festival approached, Bolivia entered an increasingly unsteady political period which would come to form the political frame for the next iteration of the festival in 2019 Calle: Identidad which took a closer look at the concept of cuerpo-territorio (body-territory) a term used widely in climate justice and feminist movements in Latin America to describe the relationships we hold between our bodies and the territories we come from and how ownership of both is shaped through the lens of extractivism, colonialism, patriarchy, and capitalism. This became particularly important as the social uprising in Bolivia reached a climax in 2019, with the stepping down/ousting of ex-president Evo Morales that took place on the third day of the festival. This political context bled directly into the performance work and into the performer’s commitment to taking public space in a time of crisis. Thinking about the third edition, Ale says:

Ale: The second edition came out really well, but it taught me more professionally what I wanted for the next one.

Anahí: Did you already know you were going to do it again?

Ale: It was a decision. This is it and this has to grow, it can no longer go backwards, only forwards. Obviously, throughout my career I was also doing performance as an artist. I participated in the first two bienials, but not in the third because it’s a very big job, to organise a biennial all on my own. The third was the biggest, there were twenty-one artists, there were three continuous days and a closing event. The third biennial was exactly the date of the political problems in Bolivia in 2019. So we did the first day, we did the second day until halfway through and there was no third day, because everything was already in chaos. It was the toughest edition for me because I invited international artists. I went to present a performance, Te ves en mis ojos, (a work about the pain of being a migrant, the pain of political chaos, the pain of being a woman in all this, the pain that everyone can see whilst you are blindfolded) at a conference in Buenos Aires, the Congreso de Teatro CON/TEXTOtipea: Performatividades (2019). There I met very interesting people from Colombia, I was able to see a friend from Brazil, and another from Argentina.

When I decide to do the third biennial, I asked them: “Do you feel like sending a video of something you’ve done? I’ll present it here”. The girls from Argentina, part of the group Vibra Mujer, who work with women from a feminist perspective, told me that they wanted to come. My friend from Brazil says to me: “I’m coming!”. In the end, four Argentinian women come, my friend from Brazil, and two Mexican artist friends who tell me that they want to participate. […] Without meaning to, the biennial becomes more international.

The theme of this Bienal Calle was Identity. I wanted to talk about everything the body as a political territory, especially within the political context of Bolivia, because before the girls arrived I told them: “Bolivia is not doing good. It looks like there’s going to be a coup. We are entering a state of siege. We can’t go out after a certain hour. Do you still want to come?” I said: “Don’t come because I don’t know what’s going to happen. Every day there are protests, I don’t really understand what’s going on, but it’s very intense.” The Argentinian women came with even more enthusiasm, poniendo el cuerpo. This biennial was very emotionally tough for all those who participated because the day it started, the police announced they were no longer working and left the streets free. There was looting. You went out into the square and there was a Christian prayer group, a Catholic prayer group, people singing songs, people who didn’t understand anything, people arguing… it was chaos. We were also there and decided that we were going to do performance. We went out into the streets and did all the performances that had to be done. Sometimes there were spectators, but it was a lot for us too because there were days when there was no one outside their house at all because it was so dangerous.

Anahí: And the people you did see?

Ale: They were grateful! […] I would say that it was the biennial of emotion. The day it ended, it ended because Evo Morales resigned. Bolivia went into total chaos. That’s when I really said: “The biennial is canceled”. The girls from Argentina didn’t present their work, they had come in vain, to do their non-performance, as they call it to this day, although they finally did it in Argentina.

Anahí: Super tough not to be able to have closure after such an intense experience.

Ale: The day of the opening, when we were all there, was the day that a state of siege was declared. People couldn’t go out from eight o’clock at night. […] And we said: “Are we going to do it?” Everybody said: Yes! For Bolivia, for art, for everything. […] It was very intense because the airport was closed and the girls were leaving on the night of the third day. Everything was canceled. We had a partial closure of the biennial at my mum’s house in the end, because all the possible places for a gathering were closed and meeting was forbidden. It became a political conversation[about what]was going on: What we think, what has happened to us, and how all this was being handled. At the same time, […] everybody around Bolivia – Brazil, Argentina – were writing to the girls’ WhatsApps saying: “It’s a coup!”. And the girls were telling us that it was a coup and we Bolivians, we were saying: “No! It’s not!” That’s what was, gathering to discuss: “Is it a coup? Is it not a coup? What’s happening to us?”. The [guests] were all mothers, and their families called them crying telling them: “You have to get out of there, you don’t know what we’re seeing on the news here”. There were things that we in Bolivia weren’t able to see. We hadn’t realized that the military was already taking to the streets… […] while we were in that discussion, they set fire to the Puma Kataris2 and that’s when everyone said: “I’m leaving”. […]

I remember going to the airport, that day was really the most extreme experience I’ve ever had in my life, […] there was no transport, they didn’t want to take us even to the airport. After talking to many, many taxis, I managed to get a taxi to take us for three times the price. There were two drivers and one was armed. He said: “I’m sorry, but I need to protect you and protect us. […]

I was in a fit of shock and anxiety, but I had to keep carrying on. Then we got to the airport and they went in. They were safe and sound… The worst thing was that the Brazilian got out, but the flight from Argentina was canceled and they were at the airport for four days. I called the Argentine embassy to see how we could help them to get them out and the embassy told me that they could take criminal proceedings against me for having brought people in and not having taken responsibility. […]

Following this, Ale was resolute that this was the last time she would host this festival, but in 2021, during a residency in Brazil, she was again approached by collaborators and friends who offered to support the first festival outside of Bolivia. So, with this renewed support, she said yes. This time, the biennial took place on the streets of La Paz as well as in Sao Paulo and online, where she hosted works by international artists from across Latin America as well as Europe and India.

Ale: That’s where the last version of the biennial was born, called Territorio – Memoria Ancestral, because in Brazil I was researching my Black indigenous roots with a women’s collective called Warmi Sankofa Ayni, they have studied ancestry and migration a lot in their work. My time there became a research on being a migrant, and what it is to be a white migrant verus a racialized migrant. So we did this biennial. All the people who participated were of diverse racial backgrounds and sexual identities. I wanted it to be like this. Everything that has been proposed from there was very beautiful. There was a lot of conversations, especially about racism. It was a really wonderful biennial. It was carried out on the basis of donations, with the support of a school of live arts, and of a lot of organising with friends. At the same time, I contacted artists in Bolivia and said to them: “Is there anyone who is up for taking to the streets?” “Yes,” said the artists, “obviously yes!” And that’s how there was a part of the biennial in Bolivia happening simultaneously. It was three days in Brazil and one day in Bolivia.

Anahí: How important are exchanges between territories or between artistic networks when you’re based in Bolivia? As you say, here there are no formalized spaces where performance artists can find a home, so I imagine that exchange with other countries is very important. Not only to go and study, but also in terms of collaboration, and the use of resources that exist elsewhere. What has your experience been with this?

Ale: Exactly. The same in terms of support [for] culture. Next year the biennial is coming – my friend from Brazil says to me: “Shall we do it in Brazil too?” I tell her that yes, and that I’m going to apply for a fund but here in Bolivia there’s nothing. She even says to me: “Or should we just do it here and totally transfer the biennial to Brazil?” I think not, because I want the festival to definitely be in Bolivia, but by doing it here it would have to again, be self-organized. In Brazil there would be space, people, collaborators, and so on. The lack of economic support in Bolivia is very, very, very tough. […]

I want to continue working on the body as territory and political space, and on territory as political space as well, because it’s not the same story that Brazilian artists have told me as what Bolivian artists have said, of course. They are not the same spectators in the street.

I was able to do a performance (Q’epi Migrante) in which I dressed completely as a chola3 and handed out coca leaves in Brazil. I was talking about this migrant myth we have in Brazil, which says that Bolivians cannot exist in the Brazilian imagination if they are not working as textile workers. There are many factories [in Brazil] where people are working in very terrible conditions. So, every time I said that I was Bolivian to anyone in Sao Paulo, they would say: “Ay” (as if they felt sorry for me). That day I wore a skirt. I really like working with wool and I wore threads from which hung scissors, and needles and I was holding coca leaves. In Aymara customs, it is said that you make a kintu – which are two little leaves of coca that you put together and give in sacred places. So, I traveled through the streets of Sao Paulo to places kintus in spaces that were ravaged by colonisation. As there are a lot of people on the streets, they came and asked me for coca leaves, because coca leaf is illegal in Brazil, it’s a drug. They could have arrested me. The police came and there was a whole conflict there with the coca leaves, which I got super illegally too, as if it were marijuana. People passed by and said: “A Peruvian?” And I explained, no, I’m Bolivian. Then others would come and say: “Is this art?” I really liked it. I love the perception I had in Buenos Aires and of Brazil as a Bolivian migrant woman.

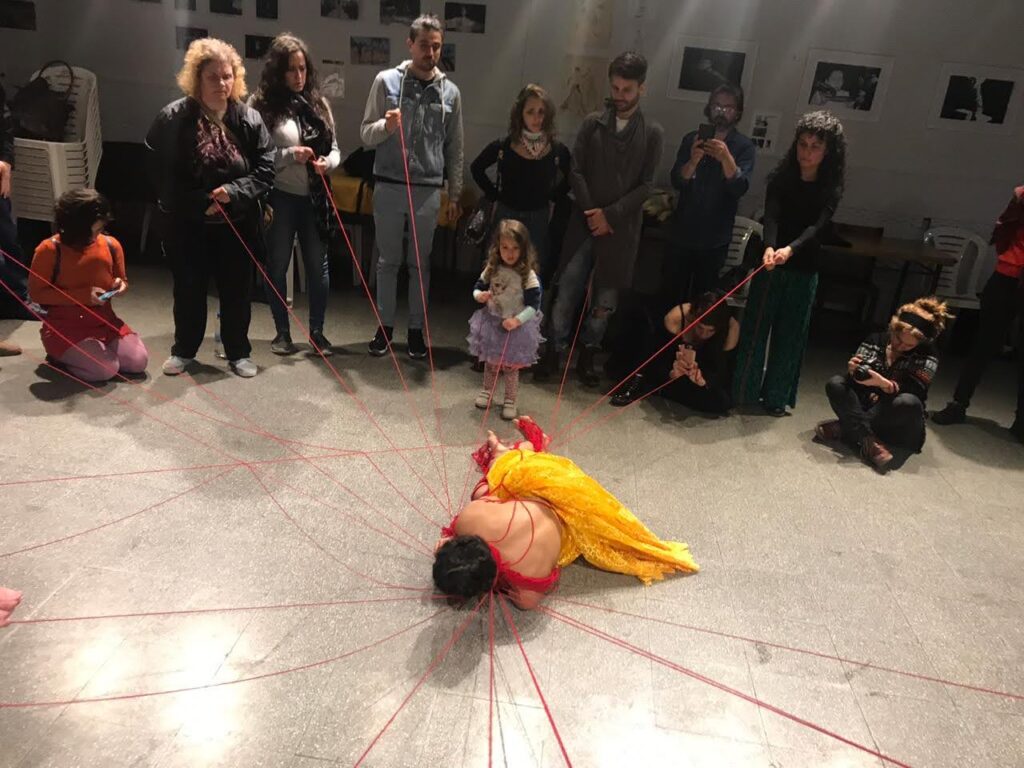

I had a final performance (Raíz), separate to the biennial in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in which I dressed again as an indigenous woman, and from my research into yarn and wool, I made a q’epi4, a super heavy aguayo5, loaded with stones. I tied it far away, with wool tied up to my feet, and in that tension, I placed little pieces of paper. I would then stand with a sign that said, “What do you think when I say ‘Bolivian Indigenous woman’?” People would come and write down their perceptions: super racist things, nice things. What I wanted was to break their preconceptions. So, I would start stretching and stretching and stretching the wool until it would break with from force of my shuffling feet.

When it was over, with the leftover threads I tied all the people in a circle, everyone tangled with everyone, I tied them together and gave them a little piece of paper asking: “Where do you come from? What are your origins? Do you think there are indigenous nations between Bolivia and Brazil? Do you know any names? What do you know about your grandparents?” Asking everyone about their origins and how they might coincide with Bolivian origins. […] Talking about migration is crucial. Doing performance in different places is important and I like that this relates to the political and to the fact that we are women. In the biennial in Brazil we were almost all women, including non binary people, trans as well, and the men that were there were diverse… but there were no cis men. I found this very interesting because in Bolivia too, who has been with me for years? It’s not cis men. It’s diverse women and men.

Compared to many projects happening across Bolivia, many of which have a longer history, Calle has remained independent and unfunded. Whilst this has given it artistic freedom, it has also meant that questions around the sustainability of the project are constant, linking to wider conversations around the embedded hierarchies of power in art spaces in Bolivia, which still heavily rely on an institutionalised vision of art that determines whether or not someone can call themselves an artist and receive funding for their work. The result of this is that many of those who want to pursue art and performance leave Bolivia to build their career elsewhere. To be able to do this, it is necessary to come from a privileged background that can support this. It is not necessarily those with the most exciting propositions that are allowed to enter local (and international) arts ecologies – it is those in structurally more privileged positions (which is to say upper class, white Bolivians).

Ale: A friend of mine in Brazil said to me: “Why don’t you show more in galleries, festivals and things like that? Your work is amazing”. I said to them, I don’t have certificates, I don’t have master’s degrees. If you ask me for my CV, I’m going to send you a CV with no institutional qualifications and just list everything I’ve done. So I am super undervalued compared to many other people who have studied outside the country, as I mentioned before. […] In a meeting with other projects in Bolivia they ask us the question: “Do you have economic support? And I said no, but everyone there said yes… A debate began where they said: “We have a history”… And everything goes back to the same hegemony. They say: “We’ve been around for]many, many years, established. We have space and we are a big team. So of course we have support.” I think that they have never given me funding because it goes to people who have a curriculum with foreign recognition. So, it’s like an endless rat race […]

I have felt this much more strongly in Bolivia than in Brazil or Argentina, which are the countries with which I have exchanged most with on these issues. All my colleagues in Brazil have some postgraduate degree, as a minimum, but that doesn’t mean [they are closed to working with you] if you don’t. But in Bolivia they are. Because of this, you don’t feel identified with the term artist [without qualifications]. Once upon a time, I used to feel that way, but today I realize that I don’t, my thinking and my creative process come from art more than from activism. I’ve been questioned by some artists who have participated in the biennial – to what extent is it an art biennial and to what extent is it an activist biennial…? In reality, it’s a combination of both.

Speaking to her own artistic practice as someone that centres public space as a stage for her work, Ale spoke further about what it means to bring political commentary to public space, and make meaning in a relational, site-specific way.

Ale: During the pandemic and the rigid quarantine in Bolivia, unfortunately, there were a lot of rape cases within families. When the quarantine came to an end, people were already working and so, I went to the street. Taking advantage of the fact that I am a small woman, I dressed up in a girl’s dress, took a teddy bear and a red cloth about four meters long. I put the cloth like blood between my legs. I went to four places in La Paz. On the viaduct between Avenida 6 de Agosto and Avenida Arce, I sat down and the cloth unfolded to the cars. The best thing about that intervention was that below, on the viaduct, there was a graffiti from Mujeres Creando that says: Aborto Libre (Free Abortion). Then I went to the María Auxiliadora church, unfurling the fabric, from the steps to the street. There, people gave me lots of dirty looks, but nobody approached me, and then I went to the Prado steps where I had a better reception. I only stayed for fifteen to twenty minutes in each place, static. Finally, at the Obelisk, a guy said to me: “I’ve been following you since the first time you did it. I didn’t know whether to talk to you or not, but thank you for what you’re doing. We get the message. I think everyone is impressed and people pass by, but it doesn’t mean they don’t see you and know what you’re saying”.

So I think as an artist this is a constant challenge, how to reach people. What do you want to say to people? And that’s where the permanent contradiction lies: if you’re going to go out on the street, you have to know how to talk to people. So you can’t be self-absorbed in your art, you have to know what message you’re giving. That’s why I’m encouraged to go out on the street, because I have something to say, I don’t want to be hidden.

Alejandra Del Carpio is a multidisciplinary artist between the performing arts, performance, and visual arts, her work explores feminism, decolonization and the investigation of her ancestry. She is the founder of the Bienal Calle, and intends to continue to grow the project both in Bolivia and Brazil, and if possible, to expand the seed to other Latin American countries for future editions. She hopes that the capacity and resources for the event will get better and better, because the artists are excellent and the pieces presented are transformative. .IG:@calle.performance

Footnotes:

1 Caserita, is the word (of affection) used to describe women on the street who sell things, in kiosks or by foot in a more ad-hoc way.

2 Puma Kataris are a fleet of modern busses and set bus lines that got launched in La Paz in 2014, they were the first of their kind in Bolivia who works on privately managed public transport system in the form of mini buses and trufis (shared taxis) all which are independently owned by those who drive them and have informal stops around the city.

3 Chola, is a term used for an indigenous woman, one who usually wears traditional clothes. It can be in a derogatory manner, with racist tones.

4 Q’epi is an Aymara word for ‘bundle’ usually one made of an aguayo.

5 An aguayo is a rectangular piece of coloured wool that Bolivian indigenous women use as a complement to their clothing and, primarily to carry their children or to carry items. Their use has spread to Peru, Argentina, Ecuador and Chile.

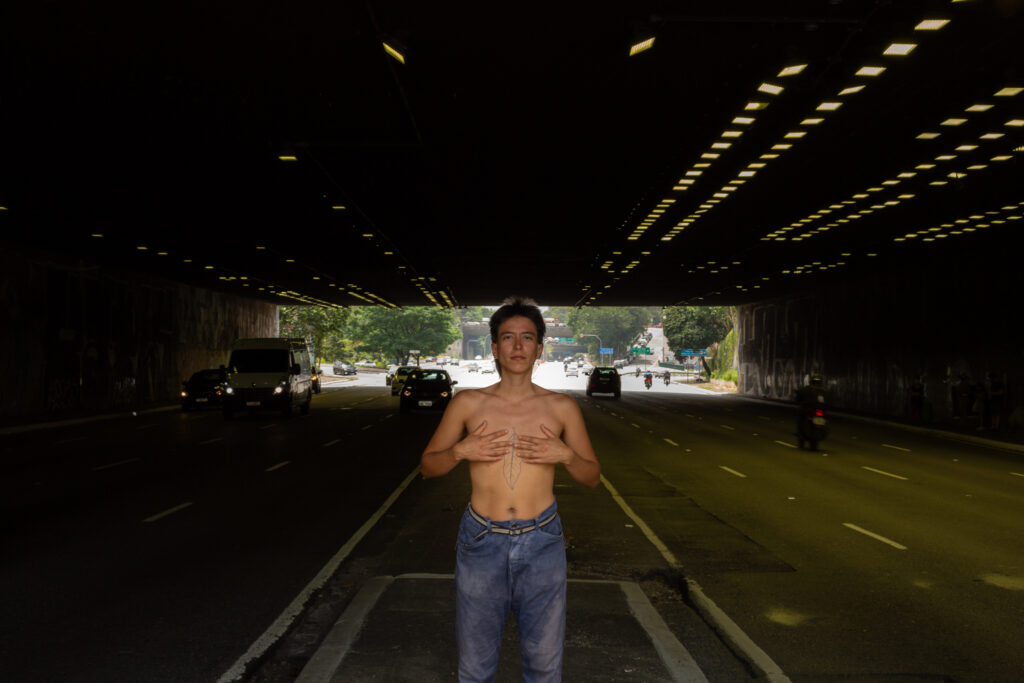

Lead image credits: Bienal Calle: Memoria – Territorio Ancestral, Closing performance, (2021)