Bojana Barltrop | December 2019

14th December 2019performingborders (Alessandra Cianetti): Bojana, recently I was rereading the catalogue of your solo exhibition ‘The Great Chain of Being’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade (MSUB) that I was lucky enough to see back in 2017. Once again, I was struck by the layers of your multi-disciplinary practice and thinking. I would like to start our interview going back to the years of Belgrade’s explosive creativity at the end of the ‘70s and beginning of the ‘80s when the city was a centre for national and international experimental art in Yugoslavia. At that time you first presented your multimedia work at the Happy Gallery in the Student Cultural Centre, a place that curator Marina Martić describes as a site for unstructured creativity, post-Warholian anything-goes sensibility, musical-visual experiments, different hybrid of performance, happening, photo-sessions as well as the centre of the new Polaroid scene. Photography, and more specifically polaroids, has been one of the main medium you have explored in your artistic practice over the years with a focus on the exploration of your body, identity as well as landscapes, histories and your own family’s stories. I’m thinking here for example of your early work like the zine Playboyana (1979), the photograph series Suicide (1981), and later photographic series such as Poets & Peonies (2016) and The Post-Oriental Condition (2016). Can you tell us more about the relationship between your photographic work and the performative quality of your still life, self-portraits, and series over the years?

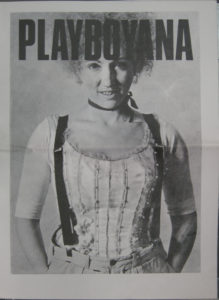

Playboyana, Bojana Barltrop, 1979. Courtesy of the Artist

Bojana: Marina’s description of the Student Cultural Centre or SKC is more or less correct. However, there will be no such Eighties, if there were no Seventies and also there wouldn’t have been the Seventies and SKC without the student revolts of 1968. However, revolts were everywhere, but something like SKC happened only in Belgrade, so, what about Belgrade?

To respond, I will start with Venice. I worked for six months, I think, in the year 2000, on a piece about Venice, its Ikona Galery and photography. I did not complete it but while working on that I discovered Marilla Battilana’s book on some English writers’ works about Venice. For example Sir John Mandeville Travels, 1371, compiled texts from various sources with little truth in it and was used as a guide book for centuries by pilgrims to Holy Land. To begin with, I opened an edition printed between 1400 and 1500. Venice was a major power in the Mediterranean at the time. ‘Package holidays’ along the pilgrims’ route were an important source of its income. Still, Mandeville did not mention Venice. Instead, there was a reference to Belgrade, a city significant to pilgrims travelling by land and on foot, and, according to Mandeville, equally cosmopolitan.

I was born into a large family, mainly from Belgrade and brought up in Belgrade by my paternal family, which, in my view, left its mark.

Founded by the University of Belgrade, with Dunja Blazevic, both liberal and farsighted, on its helm, SKC also had two galleries, ‘Large’ and ‘Small’. First, during the Seventies, under curator Biljana Tomic, SKC produced a string of internationally recognised artists including Marina Abramovic. Second, under curator Slavko Timotijevic, SKC was more like what Marina Martic described. It also changed the name into Happy Gallery to make many persons happy, including myself.

I finished my studies in Belgrade and Denmark. I had extensive knowledge of avant-garde movements of the XX century associated with Russia and the Soviet Union, and those in Europe which reached Ljubljana, Zagreb and Belgrade between two world wars. I was informed of what was happening in New York, Germany and Italy. I saw whatever was worth seeing in Rome, Florence and Venice by 1964, and among else ‘She – Cathedral’ in Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the abundance of Edvard Munch in the National Museum for Art, Architecture and Design in Oslo in 1966. I followed Documenta, and for one reason or another, considered myself a conceptual artist. I also thought that time had come for conceptual art to move on. Biljana Tomic already had given an arm and leg for her cause and artists, but I thought I did not fit in.

The crowd around Happy Gallery was much about parties, drink, maybe drugs, sex and, metaphorically, ‘rock and roll’. People dreamt about New York, Amsterdam, and having success abroad, and followed feverishly what was ‘IN’. If it was a Warhol’s ‘Interview’, they produced fanzines. When Warhol started with Polaroids, they brought to the gallery one or two of their Polaroid pictures, again because it was ‘IN’. It is not altogether fair to say, but I found that approach cheap. Marquise de Sade produced his works in a dungeon, and of course, de Sade was not the only example. I thought that if someone has something to tell, that person can do that everywhere.

I had a young family and earned a living. I did not wish to live anywhere but Belgrade. I was well travelled; not entirely, but still educated overseas. I did not follow any trends, I wished to set the trends. I published a ‘magazine’ named after ‘Playboy’, ‘Playboyana’, already as a teenager. I did not wait for Warhol to publish ‘Interview’, then copied him. I indeed used SX 70 Polaroid camera, but mainly like a paintbrush or a tool.

Biljana Tomic and Slavko Timotijevic differed very much, and the SKC and its art program were split in the middle. But apart from it, there was sharp division within Happy Gallery. I was an outsider, others were mainstream. What interested them, did not interest me – Timotijevic being bold enough to tolerate both.

I did not ‘explore’ my body. I was good looking, so, fortunate that I had a good looking model at hand prepared to work with me for hours, days and nights.

Nor I did explore my identity. My mother was a journalist, my grandmother and my great-aunts had a University education. Their mothers and grandmothers were mainly women of independent means. I was a woman, mother, wife, artist and designer. This was and is my identity.

I am aware that it sounds too technical, but I am a trained artist. I am interested in classical themes and means and visual effects. Self-portrait, still-life, and landscape are classical art disciplines, and I did and do just that. I believe that art should be perfect, and being perfect depends on perfecting technicalities. Gainsborough, and not only Gainsborough, for example, had already painted figures in gorgeous outfits on various background in their studio. The ‘Lord This’ and ‘Lord That’ would come and have their head painted in a reserved space, pay for it and hang them in their homes. We visit these country houses, see the pictures and believe that Lords This and That looked just like that. I am a purist. Background, attire, texture, light, representation are essential to my work. If a piece is called ‘Homage to Jean Genet – Irma’ than there is ‘Irma’, and as far as the public relates to it, the piece is a success. Hitchcock, Bergman, Fasbinder and other directors had cameo roles in their films. Like them, I appear in some of my works.

My grandmother’s sister had an extremely primitive camera, but her photos were, at least in my view, much better than many which I saw. There were at least three professional photographers whom I knew. One was first class and, as far as I know, focused on portraits. The second worked mainly for large publishing houses and the third, earned a living from taking photos on weddings. The first had a relatively large studio, with huge cameras of which I was frightened at first. The second had a decent studio but envied what the other had. The third did not have a studio, only a larder, a bath in her bathroom and a few necessary utensils in different corners in her flat. Moreover, she made all sorts of cakes, at the same time while doing her photos, which was sometimes bad for cakes, but never for photos. So, just from experience, I realised that photography is not about the camera, the object, but about the subject – seeing and feeling, the person behind the camera, and thus, storytelling and believing.

So, again, I do not explore anything. I record and tell. I once did and do what people are today doing with their mobile phones. Occasionally the work does and occasionally does not tell the truth.

I showed the first polaroid self-portraits, on a show called ‘Transformans’. So, I did not display my performative but my transformative abilities. Beforehand, I devoted more than three years to research into seeing, and to put it simply, visual illusions. This show was, among else, the result. I made and displayed food which was like polaroids, in dreamy, Baroque colours. As such, the event contained elements of performance. But, if seen like a performance, an adequate title would be: ‘The Hostess’.

Performance reveals. Transformation hides. It relies on visual effects, thus, depends on photography and a particular approach towards photography. On the other hand, if photos were taken by someone else, it would be the advertisements.

I once heard that painters paint to be surprised and I believe it. So, my works had little with their title at first. For example, I worked with silks, lace, embroidered textiles, petticoats, and corsets. I made a pile of shots. The pictures reminded me of a brothel. The only brothel about which I knew was one I read about in Genet’s ‘Balcony’. The text was powerful. I also did not know much more about Genet at that stage. Nevertheless, I thought that Genet deserves some sort of ‘Homage’, and what I made of some of these shots became series ‘Homage to Jean Genet.’

At this show, there was also the series ‘Inside’. This time, I started with mirrors and again made a huge pile of shots. Some reminded of long corridors in Versailles, with its doors after doors in mirrors, and in turn, of person and its complexities. I continued work in this direction and created a series about what’s hidden by a person’s appearance.

The above work – and what I mentioned is far from all – was exhausting. It was summer, I worked in a red tee-shirt. I also used ‘Fiskars’ scissors for various purposes, and they were somewhere around. I did not know whether I saw the movie about Yukio Mishima about this time or long before and realised what a hassle would be seppuku or hara-kiri. I saw scissors and thought of this film. I decided to check whether I can make, ritual disembowelment aside, an incision easily, not in my body, but in a t-shirt in approximately the same place where the ritual required. It was not, and I took a lot of pictures. Of these, 14 became the work named ‘Suicide’. Technically, I recorded the action, and not a transformation, and therefore this work is the closest to performance.

Polaroid pictures are small, and the spectator needs to focus quite a lot to find out what is in front of him. Thus, they ask from the spectator to approach them as a classical painting and either follow what the artist intended to say or shuffle them like a pack of cards in their mind and construct their own narrative. Alone, they did not say much. Piled, they are like an abstract painting, something which asks from the spectator too much.

Everything evolves, and so I did. I moved first towards design to move again, mainly, into architectural history and theory and research into the relation between desire and politics, politics and architecture, and knowledge in general. I became more apt, to use your words, to express layers of my multi-disciplinary practice and thinking. The result was the show which you mentioned at the beginning ‘The Great Chain of Being’.

Like with a majority of works, I first set the show, and then the show got its name. I borrowed the title from Arthur O. Lovejoy’s book. According to Lovejoy ‘The Great Chain of Being’ was, among else, a descriptive term for the universe which retained in Western thought, and theology and metaphysics especially its significance throughout history, and as far as the early XIX century. As far as I was concerned, I loved it and loved it as I discovered it in other, not so learned sources. The show loosely covered the period from 1979 to 2017, but within it, everything, despite the variety, fitted and the title was more than appropriate. – The works ‘Poets and Peonies’ and ‘The Post-Oriental Condition’ (2016) were closely entwined.

Around 1986, it became difficult to obtain Polaroid film, and I switched to Olympus XA 2. As soon as the first camera phones appeared, I obtained one. I already used the computer for my work and was disappointed. Finally, quirky Lomo Cameras appeared, using Fuji Instax Wide Film. Polaroid was also back on the market, the offer to include Polaroid Snap using Polaroid Zink paper, which came also in quirky 3 x 2 stickers. I was not happy with any of them, still had the opportunity to continue with what was my preferred medium.

‘Poets and Peonies’ contains a series of instant pictures with peonies in bloom from my garden in Sussex, arranged instead than in a single line, in a few lines, thus, in planes . Among these, there is also a self-portrait and a portrait of a man in a balaclava and on the sides, the Serbian and English version of the poem ‘Kosovo peonies’ by Serbian poet and diplomat Milan Rakic (1876 – 1938). Peonies appear each year in May. They are beautiful and red and remind me each spring of the country where I was born and lived, this poem and its poet. I saw once ornate, heavily embroidered pieces of Serbian national dress collected by the poet’s wife. The wife did it when he was serving at the Serbian consulate in Pristina, today’s Kosovo, and then the Ottoman Empire. It was at the home of a friend close to the poet’s family. The work is, thus, about a particular kind of sophistication: this friend, our friendship, poet, his wife and what we, so curiously, share.

‘The Post-Oriental Condition’ starts with a photo of my paternal grandmother, shot after WWI in Belgrade, then capital of Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovens in then fashionable, Art Deco style. The series ends with the photo of my maternal grandfather, an Orthodox subject in the Ottoman Empire, in Turkish dress, doing business in Vienna. Between them are dark, mainly abstract photos. These relate to those few decades during which countries which were under Ottoman rule, thus, Oriental, became independent, and more or less European. I say more or less because I believe that this Oriental is still very much present in the Balkans and it’s what makes them great.

Artists David Hockney used SX 70. Directors, Wim Wanders, Stanly Kubrick, Andrei Tarkovsky and probably many others used Polaroid while filming. Their approach did not differ much from Sergei Eisenstein’s use of drawings in his work, who used drawings probably because Polaroid was not yet invented. I did not see their Polaroids until recently. Now, I find its use associated with a particular generation and equally particular artists of that generation. Because Hockney used Polaroid, somewhat like a paintbrush. Taking pictures and presenting them in series is to a degree like movie making.

The movies ‘Blow Up’ and ‘The Eyes of Laura Mars’ tell us much about photography, although, one can argue, far from that that is produced today. In fact, as far as photography is concerned, they tell as much as reading Shakespeare tells about life.

Of course, I am aware that the above approach encompassing tolerance, mediation and meditation is rare. Moreover, it is old fashioned and decadent however I appreciate change and I wait and wonder what times will bring.

In the Head of Bruno Shulz, Bojana Barltrop, 2016. Courtesy of the Artist

performingborders (Alessandra): In our conversation about your relationship with art exhibitions, I loved the tales about The Woman Who Can Do Anything / The Woman Capable of Everything (1979). I found really interesting your approach to exhibitions as temporary, ephemeral, performative acts. Can you tell us more about your reasoning around public shows and how that stemmed, in some ways, in both dialogue and contrast with the Yugoslavian conceptual performance and visual art scene of the ‘70s?

Bojana: Each art exhibition is a performance, some of them just last too long. To show their work artists do not actually need more than one evening. For the public, on the other hand, socialising is more important than any art piece. Pretending that it is not the case it’s unnecessary. For exhibitions like ‘The Book’ and ‘Transformans’ I served food and wine matching the colours of the exhibits. Those events were great successes but they were not about art. Art, if real art, should be for the specialists only. In short, I thought and think that the relationship between artists, public and specialists should be re-thought and re-negotiated in our contemporaneity.

Both versions of the title of the exhibition ‘The Women Who Can Do Anything’ / ‘The Women Capable of Everything’ are not adequate. The problem is that in English, there is no better translation. Both translations sound rather vile to me while the show was not. I presented myself as an artist and a designer showing also my ‘kitchen art’. The public enjoyed the last so much that ate even the decorations, which, of course, was not my intention. The only printed copy of ‘Playboyana’ was a catalogue for this exhibition. It related to a collaboration with Professor Gordana Marić on her ‘An Illusive System of Acting’ and let us say, my theatre work and my work on elusive systems of seeing.

Unlike many other families, my immediate family – my aunt and her husband – lived in my paternal grandmother and her sister’s house. The house had a large garden and was full of books. I learned to read and write at the age of three and I was allowed to read any book which came into my hands. I hated children classics from Heidi to Huckleberry Finn and many other classics, Jane Austin and Charles Dickens for example. No one in my family interfered in my readings, instead, I was encouraged to develop my own thoughts and fight for them.

The atmosphere at home was lively, my grandfather was a linguist, and he had a PhD on German verbs. This was considered by others as incredibly funny. My mother was also keen on languages, as a busy journalist and she was quite militant. I really do not know when, but I was not yet a teenager, when she came with the news that towards the beginning of XXI century the borderline between sexes would disappear. No one took her seriously. My aunt was first a ballerina, then prima ballerina and her career and love affairs were considered the only serious matter in our house.

I started English classes before the age of five. I was indeed encouraged to entertain myself in various creative ways from an early stage, but with my teacher Ms Bertolino, all this turned into a true delight. My father was an architect, and from him, I was getting beautiful English and American books as presents. Highlights for me were Mary Alden’s Cookbook for Children with recipes tested by boys and girls whose photos where carefully lined on its last pages. I was also encouraged to test these recipes, translate and write them down in my grandmother’s sister’s sacred recipe notebook. I then learned to knit, embroider and subsequently saw. My father loved comics, and he introduced me to them and he would create his own in letters to me from his trips. I would also reply with comics of which I was the only author.

All this care was combined with constructive neglect. Somebody had to look after me, everybody has other things to do, and so I spent a lot of time leafing through some special books and family albums. My mother studied interior design at the Beaux Arts in Bruxelles and from there she brought two books about the Louvre Museum. I spent days sorting out what paintings I liked and what I did not. My father then brought the ‘Little Library of Arts’, and I continued sorting out books about artists whom I liked and disliked, left and right. In the albums, there were photos of four generations of my fathers family, and thus, were some sort of history of photography.

All women with whom I lived loved movies. So, they took me first to watch Disney movies. It was a debacle. I found them vile and cruel, felt sorry for the characters, cried, screamed, and finally I was thrown out from the cinema, tiny and small, with the whole family. We then struck a deal that I would behave, closing my eyes when I did not like something and remain quiet. I saw ‘War and Peace’ at around the age of eight, fell for dying Prince Bolkonsky, and so much so that I read the whole book skipping over war scenes and long dialogues in French.

My grandmother went to the theatre almost every evening, either to watch my aunt or to watch what was going on and I often went with her. This started at the age of five and went on until I was ten and I continued to go to the theatre alone as soon as I could. In my early teens I saw Paul Scofield, Diana Rig and Julie Christie on the stage in Shakespeare plays staged by Peter Brook and Clifford Williams. I was already doing all sorts of things. This experience had a profound impact on my future. I was shocked about how far one can reach by using knowledge, artistry and power of imagination.

My family cared for what I could learn at home but not much for formal education. My parents were interested only in results, and other relatives not even in them. It worked well, until University. Then, partly from inertia, partly because being bribed, I went to study art. In short, my aunt’s husband was a lecturer in photography at the Academy at Applied of Arts and he suggested that I could inherit his chair if I pressed hard.

The studies lasted five years, I had to repeat the first year, so I studied six. It rarely happened but happened to me. I bounced back successfully. Reinvigorated, I had little patience for what was taught and much more for what I thought. I realised that my uncle would offer his chair to anyone who came his way and I felt betrayed. I turned to supervisors who approved of my ideas and graduated brilliantly with the book awarded the first prize at the Belgrade book fair, then at the International Festival in Nice, France. The award opened many doors, and among other opportunities also a scholarship to study abroad.

I already said that I thought that conceptual art should move on. The show ‘The Women Who Can Do Anything’ / ‘The Women Capable of Everything’ was about direction, and direction was mainly about playfulness and perfection.

Of course, I am aware that the above is a long introduction to a short conclusion into what this exhibition was about. But as I said, I am a trained artist and trained in some other times. Times change, and what I was trained to do, and what artist did then differ very, very much, and is far from what one reads on performingborders pages.

Unlike other trained artists, I displayed from outset skills which I learned either in the family or elsewhere. Thus, showed, that in my view, everything, including everyday life, can be art. When I did it, it was almost obscene. Now, it is happening, and I am pleased.

The country in which I lived does not exist anymore and depending on which kind of propaganda one listens to or take for granted, life was either awful or wonderful. But it was not just so, the answer is much more complicated.

My parents were too young to take part in WWII. They were also born too late to be supported by any party or clique. They achieved professionally as much as they wanted. I underline ‘as much’ because we indeed lived in the one-party state, but some disagreed, and had a flock of their own. Voting rights were the norm. Women had equal rights, equal pay and hold high offices, and health care and education, including university education, were free. Childcare was means-tested but otherwise free. It was a bit of a struggle to get on the housing ladder. People lived upon the whole in relatively small flats, and of course, some did not like it. The Church was separated from the state, but people, if religious, could observe their mores. As said, it was a one-party state, and probably some neighbours were eager to report to the secret police when some of us cut their nails peculiarly. Today, Google, Facebook, Instagram did not only spy on me, they ask me to agree. People fight for all sorts of recognition, but little for common decency.

So, back to the exhibition. I had certain freedoms, and I exercised those given freedoms, including freedom of thought, and I just showed how that looked like on the exhibition ‘The Women Who Can Do Anything’ / ‘The Women Capable of Everything’. I lived then, and I live today, and this exhibition is how things were then.

In the Head of Bruno Shulz, Bojana Barltrop, 2016. Courtesy of the Artist

performingborders (Alessandra): As a Yugoslavian and British artist who has lived in the UK for more than 25 years, you have crossed many borders: media (drawing, painting, photography, performance, writing. theatre, TV), physical and legal, disciplinary (art, design, research) borders. I wonder how you have navigated this multiple border-crossing as an artist and how they have shaped – if they have! – your practice, also now that the photographic series Suicide (1981) has been acquired by Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade in 2017 and shown in the permanent collection of its newly re-opened building.

Bojana: I just quarrelled with a window cleaner, and now, I will quarrel with you as well.

In short, I do not think in term of borders, and probably, therefore, borders are not for me a problem. For me, the universe is wast and waits to be explored. Of course, we live in certain countries that allow for that. But as far as I am concerned, I am a citizen of the world, believe in artistic freedoms and human rights, and exercise them both.

My mother lived on the same estate and had three different surnames before the age of eighteen because the estate belonged to three different countries within that period. She had, of course, documents, but never a sense, of nationality. I must say, I am proud of it. For her, all people were equal.

I lived in one large country which reduced itself to a small one at whim. I live now in another, a considerably larger country, which is doing just that to itself too. It is for one life indeed too much but I cannot do anything about it.

I wept for three weeks before the Scottish independence referendum, thinking how people would vote without knowing what would await them if the independence happens, and would last for years. I do not have tears anymore. There is a great but also lovely novel by Italian poet and novelist Manzoni. Its name is ‘The Betrothed’ or in Italian ‘I promesi sposi’. It is very much about borders but also has a happy end. I have to read it again.

Unpredictably, I worked on my PhD thesis for ten years. It was essentially about desire and politics. The argument rested on Francis Bacon’s Scheme of Knowledge which Thomas Jefferson used to sort out books in his Library. In fact, Bacon never drafted such a scheme, someone else did it according to Bacon’s ‘Of Advancement of Learning’.

The dividing line between disciplines is fluid. Disciplines change. The amount of knowledge in some areas increase and in other decreases. Many get obsolete with time. Some split into subcategories. Occasionally subcategories turn into separate domains. In other words, where there were limits pushing boundaries from within, changes these limits. At the beginning of the XX century, it was still possible to know which domains of knowledge the total sum of knowledge consists.

So, borders are about divisions and boundaries about limits. The fist is tribal and the second universal.

Of course, the most attractive area of knowledge are secrets, and besides, knowing them and forwarding further. But actually, without in-depth knowledge and much tolerance, information is useless and often reduced to prejudice. It kills.

People know that Thomas Jefferson was one of the Founding Fathers, they know that he drafted the Declaration of Independence and that he was the Third President of the United States. But no one mentions some of his more radical ideas. For example, to put it simply, that passing debt from generation to generation interferes with the next generation’s basic human rights.

Cotton Mather – known, if at all, apart from America, due to his role in witchcraft trials – described “Landscape of Heaven’. According to him, the greatest reward to those who reached it after their death is the knowledge of God. Dramatically, he promises: ‘God will Penetrate thee; God will Replenish thee; God will possess thee, and Swallow thee up; and Communicate of Himself unto thee, with Overwhelming Discoveries of His Love, and Satisfaction surpassing all imagination.’

I read Jefferson’s and Cotton Mather’s works, I was struck by both, and neither took them for granted. Still, I remember bits which I found clever or enchanting. Books, other people’s experiences, observation, experimentation, discovery and although I consider myself idle, hard work, and limitless imagination, was that what among other things, helped this – as you call it so adequately – navigation.

Like Greta Thunberg, when young, I believed in science. Unlike Greta, I have not been so ambitious and did not wish to change the planet. I started with what people can do for and with themselves and through psychology. Psychoanalysis was very much on the agenda at the time, but I focused on alternative psychological movements and creativity. There were piles of papers about great artists, their hard lives, and how turmoil helped them to make great art. There was only one paper which questioned this, and I paraphrase, ‘what would all these artists produce if they lived and work in good circumstances?’

For some artists, their work is associated with pain, for me, with joy. Of course, it is not always easy, but this a separate question.

Bojana Barltrop, family photo. Courtesy of the Artist

Bojana Barltrop was born in 1949 in Skopje, Yugoslavia. She has an MA and MPhil from the Academy of Applied Arts in Belgrade, and PhD from Architectural Association School of Architecture in London. In Copenhagen, she attended specialist studies at the School for Art and Design (Skolen for Brugkunst) and the Royal Graphic Arts College (Grafiske Hojskule). During the 1980s she was the design programme editor at the Sebastian Gallery in Dubrovnik. She had solo shows at the Happy Gallery in Belgrade (1979, 1982); at the Museum of Applied Arts (1992), the Belgrade Cultural Centre (1992) and at Gallery ‘Legat Rodoljuba Colakovica i Milice Zoric’ staged by Museum of Contemporary Art at Belgrade (2017). Her work was included in the exhibition The Art of Photography and the Serbs 1893-1989 at Gallery at the Serbian Academy of Sciences (1991), also in Belgrade. Aside from performance and photography, Bojana Barltrop is involved with theoretical work, stage design and design. She lives and works in West Sussex, GB.

Featured image credits: Bojana Barltrop, Courtesy of the Artist.